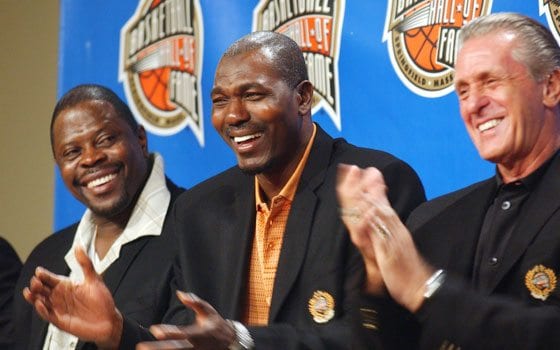

Former NBA players Patrick Ewing (left) and Hakeem Olajuwon (center) and coach Pat Riley share a light moment during a news conference at the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., on Friday, Sept. 5, 2008. All three were among those inducted into the Hall in this year’s class, which also included Dick Vitale, Adrian Dantley, Bill Davidson and Cathy Rush. (AP photo/Nathan K. Martin)

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. — Hakeem Olajuwon, Patrick Ewing and Pat Riley were enshrined into the Basketball Hall of Fame last Friday night, but it was inductee Dick Vitale who, as expected, stole the show.

Others in the class, which also included Adrian Dantley, Detroit Pistons and Shock owner Bill Davidson and former Immaculata University coach Cathy Rush, gave speeches. But the ESPN commentator held court, preaching with passion for almost 30 minutes about everything from basketball to broadcasting to family.

He connected all three in a story about his dad, who pressed coats during the day and was a security guard at night.

“I’ve been stealing money talking about a game, getting paid,” he said. “That’s why it breaks my heart when I see some athletes, chips on their shoulder. Are you serious? Flying charter planes? I don’t want to hear about 80 games a year. What other job do you get four months’ vacation? Are you serious? Making millions if you can’t play.”

Vitale, who coached high school, college and briefly in the NBA, was enshrined as a contributor to the game after spending the past 30 years becoming the voice of college basketball — extolling the virtues of “PTPers (prime time players),” screaming “Awesome baby!” and being passed overhead through student sections across the country.

It was Vitale who nicknamed Olajuwon “The Dream” during his freshman year at Houston, where the 7-footer led the Cougars to three Final Fours. In the NBA, Olajuwon had 27,000 points, 13,747 rebounds and 3,830 blocks

“It was a dream that came true,” he said.

Ewing also went to three Final Fours at Georgetown. He scored just under 25,000 points and had 11,607 rebounds in the NBA, becoming the New York Knicks’ career leader in points, rebounds, blocked shots and steals, and earned two Olympic gold medals.

Olajuwon was asked about the friendly rivalry he and Ewing shared while becoming two of the greatest centers in basketball history.

“Who said it was friendly?” Olajuwon replied.

Ewing’s Georgetown Hoyas beat Olajuwon and the Houston Cougars in the 1984 NCAA championship game. But Olajuwon earned two NBA rings in Houston, the first 10 years later, by beating Ewing’s New York Knicks in a seven-game series in 1994.

“I could not picture my career without Patrick,” Olajuwon said before the induction ceremony. “We are so intertwined from college. We play alike in so many ways. We are blocking shots, steals, intimidation. When Patrick is at the other end of the floor, you know you are playing against your toughest opponent.”

Ewing, who came to the United States from Jamaica at the age of 12, said he felt a kinship with Olajuwon, who grew up playing soccer and team handball in Nigeria. Both, he said, found their identity while playing basketball in their new country.

“When I played against Hakeem, I definitely wanted to be at my best,” Ewing said. “I think he feels the same way. We both know what each other brings to the table — intensity, energy, effort. You would have to put out 110 percent to play against each other.”

Riley, after winning championships as a player and assistant, won five more as a coach — four with the “Showtime” Los Angeles Lakers of the 1980s, and another with the Miami Heat in 2006. It took that final title, Riley said, to convince a lot of people that he really was a good coach.

“I truly believe that what happened in Miami validated what probably a lot of people felt that I might not be able to do, and that what I did in New York and what I did in L.A. maybe was because there was just a lot of good players,” said Riley, now president of the Heat.

Dantley, who made it in after being a finalist for the Hall of Fame six other times, also spoke of validation. He played for seven NBA teams during his 15-year career, scoring over 23,000 points. But he never felt that he got the respect he deserved.

“Ever since I’ve been in high school, I’ve dominated at every level, but my critics always had something to say about me,” Dantley said. “All those other guys, they were supposed to get in, they were talented. But I got in through hard work.”

Rush, a pioneer in women’s sports, had been nominated five other times. That’s just 10 fewer than the number of games she lost in her coaching career. She was 149-15 in her seven years at Immaculata, leading her team to three consecutive national championships between 1972-74, despite playing with no gym, and one set of uniforms. She could only take eight players to the first championship tournament, and had to fly standby.

“I accept this honor for all of the women who coached and played so many years ago, who have been forgotten, whose scores and skills have never been brought to the fore, but they played for the love of the game,” she said.

Davidson, whose teams have won three NBA titles and two in the WNBA, enters the Hall of Fame as a contributor. He played a key role in structuring the NBA’s salary cap and free agency systems. Davidson was also among the first owners to put NBA teams on private planes and luxury boxes closer to the court in arenas.

(Associated Press)