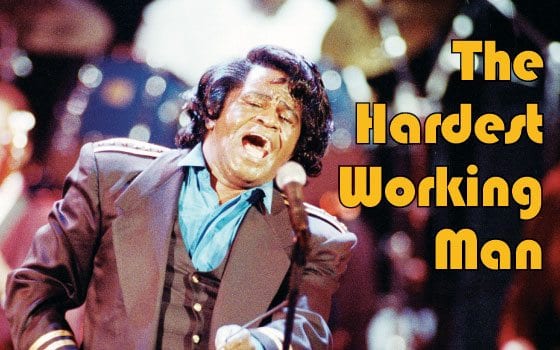

A new book chronicles James Brown’s defining moment

In 1969, James Brown graced the cover of Look magazine, with the headline “Is This The Most Powerful Black Man in America?”

James Sullivan’s new biography, “The Hardest Working Man: How James Brown Saved The Soul of America” (Gotham Books), makes a compelling case that on one night, in the midst of unspeakable tragedy, he was.

Even offstage, Brown always had a flair for drama and a healthy ego. “I was the one who made the dark-complexioned people popular,” he once said.

Yet that grandiose self-importance was always tempered. In September 1968, the singer wrote in his monthly column in entertainment magazine Soul: “I’ve been acting as a spokesman to my people. Keep in mind, I haven’t been acting as a spokesman FOR my people — I’m not qualified to do that. I don’t know who is.”

And in a televised address following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination — the moment when, Sullivan argues, Brown cemented his legend — he said he hoped the movement “ … don’t cost no more lives … I’ll be doing everything I can to make sure … And I — I might give my life … ”

But, more to the question Look magazine posed about the extent of Brown’s “power,” “The Hardest Working Man” examines Brown’s influence and finds it vast. In a cultural sense, Brown filled the black leadership void that emerged after King’s death.

Brown believed his working-class roots only enhanced his reach: “Dr. King himself wasn’t a street person. I was. I came from a ghetto and was close to the people in the ghettos all over America.”

Soul Brother No. 1 had street cred, earned in part by message tunes such as 1966’s hip-talkin’ “Don’t Be a Dropout.” His appeals to black youth to study and seek entrepreneurship reached millions through black radio, sold-out concerts and appearances on television talk and public-affairs shows.

Sullivan’s book is framed around the single event: April 5, 1968, the night after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., as more than 100 U.S. cities erupted in violence. On that evening, Brown had a concert scheduled in Boston.

This was the city where King earned his doctorate and met the woman he would marry, Coretta Scott. Known as the “Cradle of Liberty,” Boston had experienced three nights of violence in 1967 after a skirmish between police and black protesters. And on the night of the Brown concert, activists in Roxbury, the city’s largest black section, had urged residents to stay off the streets.

Local black leaders convinced the mayor of Boston, Kevin White, not to cancel the concert but to televise it to encourage would-be troublemakers to stay home. Boston’s sole black city councilman, Tom Atkins, led negotiations between local public television station WGBH, a reluctant mayor (who had never heard of Brown), influential private financiers, the venue at Boston Garden and Mr. James Brown himself.

Brown had his own reasons to worry about the concert: He didn’t want to jeopardize a contract he’d already signed for exclusive film footage for a future TV special. He also worried some of his fans would choose to watch the show from their homes.

The show did go on. An ominous mood cloaked the arena, where a crowd of less than a fifth of the capacity attended. Roxbury experienced only minor violence and vandalism. Brown, Atkins and an empathetic mayoral assistant named Barney Frank, who would later become a congressman, were applauded.