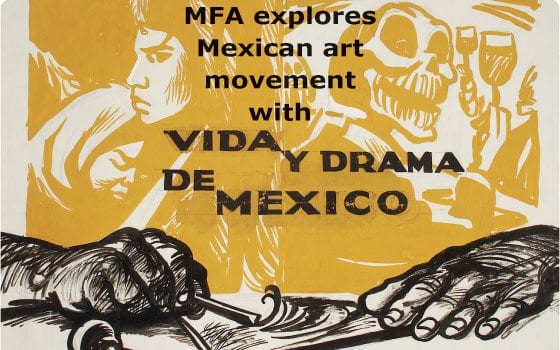

(“Vida y Drama de Mexico,” 1957, Alberto Beltrán; Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

During the first decades of the 20th century, Mexico was making its convulsive transition from dictatorship to democracy. After the ousting of strongman Porfirio Díaz in 1910, the nation plunged into a seven-year civil war. More than 2 million people died or fled the country during the Mexican Revolution. But in its wake, Mexico emerged with a progressive, modern spirit. Its artists were part of the transformation.

As Mexico instituted political, economic and agrarian reforms, some of the country’s greatest artists were developing a unique vein of Modernism. Using a new, distinctly Mexican visual language, they created images that stirred civic passion for a nation reinventing itself. Some turned to the printing press, a tool with a long history in Mexico, which in 1539 received the first press in the Americas.

At the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), the exhibition “Vida y Drama: Modern Mexican Prints” shows 32 works by two generations of artists during these turbulent decades. One section, “The Modern Mexican Masters,” displays prints by painter Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991) and the nation’s three great muralists: Diego Rivera (1886-1957), José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974).

Another section shows works by group of younger artists who in 1937 founded the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a workshop that was active until 1957. Alberto Beltrán conveys the TGP’s mission in his poster for its 20-year retrospective, “Vida y drama de Mexico — 20 años del Taller de Gráfica Popular.” A printmaker’s hands etch an image of an ordinary man, whose life and struggles the TGP make visible, while a tuxedo-clad skeleton represents the “drama” — Mexico’s bloody conflicts, political corruption and economic exploitation.

While adapting techniques of Renaissance fresco painters, as well as the U.S. and European avant-garde, Mexico’s early Modernists also looked to their country’s own traditions, including its pre-Hispanic heritage and folk art icons.

They developed a visual language to portray both the grotesque and glorious events of their times, blending the pared-down lines of abstract expressionism with imagery that could express the macabre, monstrous and surreal — often with savage satire.

These events included the Spanish Civil War and World War II, which the TGP connected with Mexico’s own political struggles.

A rifle’s bayonet gouges the eye of a fanged Hitler as U.S., British and Russian flags rise above flaming pyre of fascist symbols in “¡Victoria!” (1945), a color linocut by TGP member Angel Bracho (b. 1911) that celebrates the victory of the Allied and Red Armies.

Mexico’s ubiquitous skulls inspired the “calevaras,” the wily, grinning skeletons that populated the cartoons of Mexico’s first modern satirist, José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). Although Posada’s works are not on display, his influence pervades the show.

In Posada, Mexico’s Modernists had a homegrown artistic ancestor. Churning out thousands of mass-produced penny broadsheets, or “hojas volantes” (flying leaves), Posada used skeletons to caricature high-society dandies and other figures of power during the long reign of Díaz. After censors ran Posada out of his hometown, he moved to Mexico City, where as boys, Rivera and Orozco frequented his print shop.

Early in their careers, Rivera and other Mexican artists traveled to New York and the art capitals of Europe, joining the international give-and-take that was revolutionizing art. Siqueiros explored the accidental effects of industrial paints, experiments that influenced Jackson Pollock and other artists who were seeking new ways to express the unconscious.

Although Tamayo ended up living in New York and Paris, the light and landscapes of Mexico would infuse the semi-abstract paintings he made throughout his career. On view is Tamayo’s powerful woodcut “Virgin of Guadalupe” (1926-1927). The image has the spare geometry of pre-Hispanic art and its praying figures evoke the ancestry of Tamayo, a Zapotec Indian.

Friends and rivals, Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros created epic murals that covered the public buildings of Mexico. Their super-sized national narratives attracted Mexico’s capitalist neighbor to the north. Ford Motor Co. hired Rivera, a loyal Communist, to immortalize its factories. His mural at the Detroit Institute of the Arts on the evolution of technology links the Ford plant with early Aztec and Mayan achievements in engineering.

The artists known as “Los Tres Grandes,” or The Three Great Ones, also turned to lithography, which enabled them to create art that was portable in scale and readily reproducible for fine-art patrons.

A masterful lithographer, Rivera varied the pressures on the engraving plate to create prints that rival drawings in their refinement and tonal range. Among the prints on view is Rivera’s lithographic montage of his wife, the renowned Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. Like a surreal X-ray into her psyche, the two-sided print portrays her as a mysteriously androgynous figure. His strikingly vulnerable self-portrait, “Autorretrato” (1930), shows his plump jowls and fleshy face.

Rivera’s elegant, curvilinear lithograph, “Zapata” (1932), portrays peasant-turned-military leader Emiliano Zapata outfitted in white, standing by a white steed and holding a scythe. Surrounded by totem-faced workers and peasants armed with bows and arrows and hoes, he plants his foot on a dead soldier’s sword — celebrating a revolution fought by those close to the earth.

Another Rivera lithograph, “Escuela al aire libre” (“Open Air School” 1932), is a pastoral scene in which a solemn circle of peasants and children learn to read, while behind them, farmers till fields and a rifled guard stands on protective watch.

As muralists and printmakers, Rivera and Orozco were telling different stories. While Rivera idealizes the Revolution, Orozco depicts its human toll and the corruption and atrocities on both sides of the war. Orozco’s print “La retaguardia” (“Rear Guard,” 1929) depicts with spare, slashing strokes a band of “soldaderas,” the women who followed their men into battle and sometimes fought alongside them. The print shows some carrying rifles, others pitchforks and hoes, and still others, babies.

Like Rivera, Orozco took U.S. commissions. But his fresco in the Baker Library of Dartmouth College portrays the saga of the Americas as an epic tale of greed and violence. The mural starts with the Aztec and Spanish conquests and concludes with a machine-age meltdown, an apocalyptic vision of Christ destroying his cross in a smoldering wasteland.

Orozco’s lithograph “Las masas” (“The Masses,” 1935) could be a scene from Dante’s “Inferno.” The satirical image portrays the monstrosity of a mob, which Orozco depicts as a quivering, inhuman pack of flag-waving figures with enormous, howling mouths.

Perhaps Posada’s closest kin in the MFA show is Leopoldo Méndes (1902-1969), a TGP founder and masterful printmaker. In his hands, even artists become the butt of satire. A display case holds his wood engraving “Concierto de locos” (“Fools’ Concert,” 1943).

The print caricatures several prominent reformers and artists, including Rivera and Siqueiros, who are each plunking on a different instrument, out of tune with their times and each other. Following an expose of tainted milk sales, Méndes produced a linocut that shows a female “calavera,” half-woman and half-cow, firing a rifle at another hybrid, a can of milk in a businessman’s suit.

In 1942, as Mexico joined the Allies, Méndes produced one of the first depictions of Jews being transported to Nazi concentration camps. In his stark linocut “Deportación a la muerte” (1942), a cloud of thick black smoke trails a long line of boxcars. One is open, and a soldier’s lamp lights the gaunt faces of the captives, etched with a few expressive lines. Drawn with forceful gashes, the boxcars look like coffins.

This small powerhouse of an exhibition shows artists developing a new visual language while bearing witness to their times.

Posada’s calevaras adopted an icon deeply rooted in the Mexican psyche, evoking the equalizing power of death. Although death has the last word, by wielding its symbol, Posada and the artists that followed him brought truth to life.

“Vida y Drama: Modern Mexican Prints” is on view through Nov. 2, 2009 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston. It appears along with an exhibition in the adjoining gallery, “Viva Mexico! Edward Weston and His Contemporaries,” which explores the photographer’s two formative sojourns in Mexico during the 1920s. For more information on the exhibits, visit http://www.mfa.org.