The renowned American figurative painter Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) brought a Harlem-honed social consciousness and spare, Cubist-inflected style to works that were masterpieces of visual storytelling. One series of his narrative paintings is on display through December 15th in a small, powerful exhibition at Harvard University’s W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research.

Entitled “Resistance and Revolution: The Toussaint L’Ouverture Prints of Jacob Lawrence,” the exhibition presents 15 large silk-screen prints that Lawrence created between 1986 and 1997 from his 1937-38 series of paintings, “The Life of Toussaint L’Overture.” Lawrence was just 20 when he painted the originals, 41 tempura panels that tell the story of the slave who rose to lead the liberation of Haiti.

Lawrence followed this first series with other chronicles of black struggles for social justice. Another project, which he painted from 1940 to 1941, was a 60-panel narrative of the African-American migration from the rural south to the urban north after World War I. The cycle earned him international fame at age 24 and brought an untold story to the forefront of the American imagination.

Raised in Harlem by his mother during the Depression, Lawrence took after-school art classes at the Utopia Children’s Center, where he met his first mentor, the artist Charles Alston. He dropped out of high school at 16, and while working at a laundry and print shop, continued to study art with Alston at the WPA-sponsored Harlem Art Workshop. Its programs drew prominent figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including the writers Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, and Ralph Ellison as well as such artists as Archibald Motley, Loïs Mailou Jones, and Romare Bearden.

“It was like a museum without walls,” Lawrence once told an interviewer. He also routinely walked the 60 blocks from his home to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and frequented the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library.

At first, Lawrence painted scenes of daily life in Harlem, rendering its hardships and vitality in the vivid palette that he saw in his home and neighborhood. Using poster paints that he could buy for 15 cents a jar, he applied flat, primary colors in boldly contrasting juxtapositions. “I didn’t mix colors,” Lawrence says in the video interview on display at the exhibition, filmed three weeks before his death. “I liked it pure as it was.”

At age 19, he already had his signature pared-down style, which coupled a strong sense of design with spare, expressive lines. In the video, Lawrence says, “Why use three lines when one will do?”

Encouraged by his mentors, Lawrence turned to telling the stories of African-American heroes, starting with L’Ouverture. “No artist had yet undertaken such an ambitious project,” says the exhibition curator, Patricia Hills, a professor of American art at Boston University and a 2006-2007 Du Bois Institute Fellow.

His models for visual storytelling, notes Hills, included a book of woodcut prints by Belgian-born artist Frans Masereel (1889-1972). His wordless novel, “The City” (1925) depicts everyday urban life in its violence and teeming energy.

Lawrence’s series rendered epic stories on a close-up, human scale. He wrote a title and his own brief text to accompany each panel, which presents an episode of the story.

Starting with his first series, he used the same method to produce the panels, each 11-by-19 inches in size. “He carefully designed each picture, outlining what he wanted and then going back to fill in the colors,” says Hills, who was a long-time friend of both Lawrence and his wife Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, also an artist.

After spreading the papers out, he would apply one color at a time—for example, all reds, and then all blues—to visually unify the series.

Now at the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans, the 41 paintings in the L’Ouverture series follow the life of the man who abolished slavery in Haiti, the first country in which slaves successfully rebelled and won their freedom. The panels move from his birth through his victories over French, Spanish and English battalions to his betrayal and capture. Although he died in a French prison in 1803, the year after, Haiti became an independent nation.

In 1939, when he was 20, Lawrence presented the series in the first museum exhibition of African-American art, held at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

One year later, Lawrence painted his epic migration cycle, which the Museum of Modern Art in New York displayed in its first solo exhibition dedicated to a black American artist. MOMA also organized a nationwide museum tour of the paintings, and “Fortune” magazine published 26 of its 60 panels.

After serving in World War II in the U.S. Coast Guard, Lawrence returned to New York and began a distinguished college teaching career. In the ’70s, he and his wife moved to Seattle, where he joined the faculty of the University of Washington, retiring with emeritus status in 1986.

Soon after, he began working with master printer Lou Stovall to translate 15 episodes of his L’Ouverture series into silk-screen prints. The resulting images are larger than the originals, and while faithfully replicating the paintings, the silk-screen versions have a smoother finish that sharpens lines and colors.

The heightened graphics accent the visual haiku of Lawrence’s compositions, which communicate telling details with spare expressiveness.

He depicts the newborn L’Ouverture with a cartoon-like pair of ovals. A furrowed brow conveys the concentration of leaders planning their strategy. Against a sea of blue, Napoleon’s boats are simply lines and curves in gold topped with the French tricolor.

Along with a uniform palette, Lawrence also created a vocabulary of recurring shapes for each series. Silhouettes interlock like puzzle pieces in various ways throughout the cycle.

The cylindrical form of stovepipe hats repeats in many images. Soldiers’ faces are mask-like triangles. In “The March” (1995), the matching uniforms and muskets of the troops create surging, multi-colored diagonals. Sugarcane starts out green, but as the rebellion progresses, the leaves gain bands of red that suggest tongues of flame.

The second-to-last scene shows the captured L’Ouverture; but Lawrence does not end his story there. His final print, “To Preserve Their Freedom” (1988), looks forward to the ultimate triumph of L’Ouverture’s rebellion in 1804, when his successor leads Haiti as an independent republic.

In its caption, Lawrence writes, “Black men, women, and children took up arms to preserve their freedom.” Four figures brandishing weapons move forward as if in a choreographed dance. The three men and a woman resplendent in a red and yellow head wrap, white top and red skirt advance in a field of gold. Behind them, a blue backdrop evokes the mountains of Haiti.

Reflecting on a lifetime of works that honor black achievements with a compassion and beauty that transcend politics and race, Lawrence has said, “I’m dealing with struggle…I think struggle is a beautiful thing. I think it is what made our country what it is, starting with the revolution.”

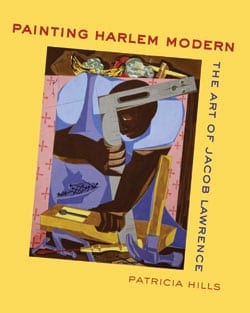

On October 29th at 6:00 PM, exhibition curator Patricia Hills will give a free lecture at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, 485 Broadway, Cambridge, based on her new book, “Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence,” the first comprehensive study of Lawrence in the context of the Harlem Renaissance.

The W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research is located at 104 Mt Auburn St. Floor 3 Rear in Harvard Square, Cambridge. Admission is free to the exhibition, which is open weekdays from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. Find out more at http://dubois.fas.harvard.edu/rudenstine-gallery

View the original series at:

http://www.jacobandgwenlawrence.org/artandlife04.html.Under series, select “The Life of Toussaint L’Overture, 1938.”