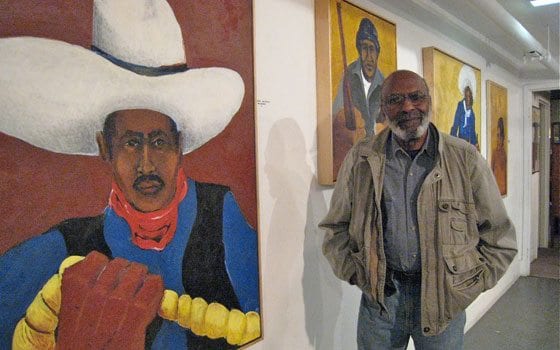

Author: Sandra LarsonArtist Hank Kearsley with part of his “Black West” series. Kearsley has researched the lives of ex-slaves and other black men and women who were part of settling the American West. These paintings are part of a larger exhibit, “Quest for Freedom: A Visual History,” at the Gallery at the Piano Factory through Feb. 28.

Hank Kearsley is a teacher at heart.

Viewers of “Quest for Freedom: A Visual History,” the 80-year-old artist’s exhibit at the Piano Factory Gallery this month, will surely encounter some history not often taught in schools.

The larger-than-life portraits in his “Black West” series, for instance, highlight the stories of blacks who went west after emancipation.

Bass Reeves was one of them. Born into slavery, Reeves became a U.S. Marshall in the Indian territory of Oklahoma in 1875.

Another was Mary Fields, a.k.a. “Stagecoach Mary,” a big, tough, cigar-smoking woman who survived wolves and blizzards while making deliveries for a Montana mission school for Blackfeet Indians. She also drove a U.S. mail route, opened a restaurant and started a laundry service.

Another African American pioneer, Alvira Conley established a laundry business in a Kansas frontier town before becoming a governess and traveling the world with her employers, a wealthy family that supplied dry goods to the railroads.

Kearsley moves beyond individuals and captures communities in other paintings. One of these depicts Boley, Oklahoma, a prosperous, predominantly black town formed in the early 1900s, one of the few towns still in existence.

“I think of what they did to black townships,” the artist said while making final tweaks in the gallery the night before the opening. “Once they got prosperous, they tore them down.”

Kearsley’s “Migration” series portrays the south-to-north movement of black people between the 1920s and the 1960s.

“People came north any way they could—trains, cars, whatever—and came to [the cities] looking for jobs,” he explained.

His own mother was part of that migration, coming from the south as a young woman to Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y. where she worked in the home of a wealthy family. Kearsley’s father was a local man who worked as a chauffeur.

Later on his father would open the first black-owned business in Croton, an ice delivery business.

Other works stem from Kearsley’s own modern-day experiences.

“Racial Profiling” brings to life the terror of being pulled over on a New Jersey road by seven cops. The officers let him go—but “it was pretty scary,” he said, “I didn’t know what they were going to do.”

In the painting, the traffic stop melds with visions of jail cells, lynched bodies and Ku Klux Klan robes. A trooper’s necktie is exaggerated to look like a rope.

“It’s all about telling stories,” he concluded.

“Slave Garden” was born of a trip Kearsley took to South Carolina, where he found plantations turned into resorts. Golf courses cover land once tended by slaves, and former slave quarters are rented out as vacation homes. His painting suggests the bodies of slaves under the ground, and shows a slave woman sewing a quilt, which becomes the shirt of a white golfer.

Kearsley paints with oils and acrylics and often adds collage elements with found materials. Sometimes all three come into one painting, “probably because I taught for so many years,” he explained. “When you teach, you use everything. Different materials give me texture. But it’s all shapes and colors, that tie in with each other.”

He became interested in art in about fourth grade, he said. His first drawings and paintings were of the New Croton Dam, which his grandfather had worked on.

In 1949, he went to the Art Career School to study commercial art. Then for years, he drove a truck, worked on a farm and found himself too busy to do much art. Eventually he took a night job at a V.A. hospital in order to attend classes at New York University by day. He earned a B.S. in Art Education there in 1963, and later an M.F.A. at City College of New York.

After several years teaching in Peetskill, N.Y., Kearsley moved to Massachusetts, where he taught art to middle schoolers in the Wellesley Public Schools for 24 years. He retired in 1996, but is still a frequent substitute teacher. He also teaches adults at his home studio in Newton.

At the reception for “Quest for Freedom,” some of his current and former students were in the Boston gallery.

“He’s more like a mentor,” said freelance photographer Nathan Fried-Lipski, 28, who learned his craft from Kearsley. “I learned in his darkroom, and now I make my living in photography.”

Julia Keith, 23, met Kearsley when he substituted in her sixth-grade art class in Wellesley. He told her about his summer art programs for kids. She participated in the programs for years before going away to college.

Now she’s back in the area, and taking Kearsley’s studio classes, even though her career has taken her in a different direction.

“He’s an incredible teacher,” she said. “He leads by example, but doesn’t push students in any particular direction.”

At 80, Kearsley hasn’t slowed down much. When he’s not traveling on artist fellowships, he’s in his studio nearly every day, painting and doing research. He used a cane for occasional support at the Feb. 6 reception—but he still plays tennis. He’s talking with a gallery in New York City about a possible exhibit.

He does some photography, and he’s experimenting with sculpture, mainly carved wood—still figurative, and mostly on the theme of slavery. He’s not sure, though, if that’s his next big thing.

For one thing, teaching takes a lot of his time. But it is rewarding, with both kids and adults, he said.

And then there’s the pull of painting. “I’ll start a sculpture,” he said, “and then I see something I want to paint, and I start painting.”

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)