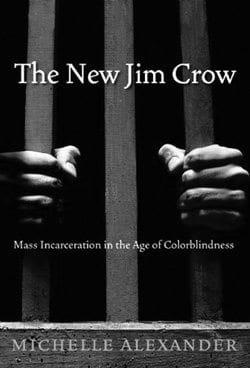

In her new book, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” legal scholar and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander argues that despite claims of colorblindness, the United States has not done away with the “racial caste systems” of slavery and segregation — instead, it has simply transformed them.

Incarceration rates have exploded in the past 30 years — in 1980, about 300,000 people were behind bars; in 2008, there were 2.3 million.

Today, more African Americans are under the control of the criminal justice system — through prison, jail, probation or parole — than were enslaved in 1850, 10 years before the start of the Civil War.

Even apartheid South Africa imprisoned a lower percentage of its black population.

The primary cause for this has been the War on Drugs, a war declared by Richard Nixon and set into motion by Ronald Reagan.

Reagan officially kicked-off the War on Drugs in 1982, even though in the same year, less than 2 percent of Americans saw drugs as an important problem facing the country. The drug war was also declared years before “crack,” a crystallized form of cocaine, appeared in American cities.

Today, about half a million people are behind bars for drug offenses alone, and an astounding 31 million people have been arrested for drug offenses since the War on Drugs began. These drug offenses alone account for the boom in the prison population.

Today, about 2 million people — mostly African American men — are locked behind bars in the United States. African Americans are so disproportionately affected by mass incarceration that one third of all young African American men are under some form of correctional control.

Despite its veneer of colorblindness, Alexander argues, the criminal justice system has produced a racial caste just like those before it — segregation and slavery.

While Americans of all races use and sell drugs and nearly identical rates, blacks are targeted, arrested and imprisoned at enormously higher rates than whites. Examples of racial bias can also be found in racial profiling, militarized policing in poor neighborhoods of color, and minimum sentencing laws of crack cocaine versus powder cocaine, among others.

But also, Alexander explains, mass incarceration is a form of legalized discrimination and political disenfranchisement, like segregation and slavery once were. Former inmates are subject to discrimination in employment, housing and public benefits — ex-offenders can be legally denied jobs, public and private housing, food stamps and welfare. In addition, ex-offenders are frequently required to pay fees from their detention, trial, and jail time, and the state can garnish up to 35 percent a person’s paycheck after release to cover these expenses.

Through felony disenfranchisement laws, mass incarceration also denies millions of African Americans the right to vote each year, just as Jim Crow and slavery once did. Since the War on Drugs began, as many as one in seven African American men have lost the right to vote — in some areas, this rate is as high as one in four.

The Supreme Court has also worked to enshrine the prevailing racial caste system, as it once did in Dred Scott v. Sanford, which denied blacks citizenship, and Plessy v. Ferguson, which established the doctrine of “separate but equal.” In 1987, the Court ruled in McCleskey v. Kemp that racial bias cannot be challenged under the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause except with evidence of explicit, discriminatory intent.

Alexander does concede that today’s mass incarceration differs from segregation and slavery in a few key ways. The most important is the lack of outward racial hostility. After the civil rights movement, open racial animus was no longer tolerated in American public discourse, but racism did not disappear — it simply adapted to the new “colorblind” society.

Alexander notes that in the 20th century, the political fault lines of crime and racial policy were the same, so politicians advancing a tougher crime legislation also opposed civil rights legislation and vice versa.

As an activist, Alexander is not short on radical solutions to America’s “human rights nightmare” and its attitude of colorblindness that “has blinded us to the realities of race in our society.” Calling on civil rights advocates, African Americans and whites to take on the entire institution of mass incarceration, Alexander implores her readers with the urgent words of James Baldwin: “We cannot be free until they are free.”

“The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” by Michelle Alexander. The New Press, 2010. Hardcover $27.95.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)