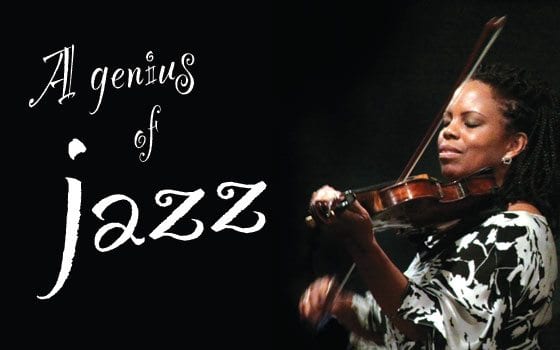

Classically trained jazz violinist Regina Carter recently dropped her latest CD “Reverse Thread” and it captures a full range of human emotions in African folk songs

Classically trained jazz violinist Regina Carter recently dropped her latest CD “Reverse Thread” and it captures a full range of human emotions in African folk songs

Sometimes music delivers like nothing else can. So it was on Saturday night at the Regattabar in Harvard Square, where jazz violinist Regina Carter and her ensemble performed the final show of their two-night stay before a transported audience.

To call their deeply joyful performance jazz would be beside the point. It was music that defies categories and generates unbridled emotional richness through songs that take in pain and loss and leave listeners high on being alive.

In her seventh and latest album as a leader, “Reverse Thread,” Carter, 43, has mined old folk tunes of Africa drawn from ethnographic field recordings in the archives of the World Music Institute in New York City. Together with her ensemble, she has breathed new life into traditional songs while keeping their uncomplicated power intact.

The exploration of old and new songs from Africa is the latest leg of a musical journey that Carter began as a toddler in Detroit, where Suzuki violin lessons led to classical training and performances in symphonies as well as Motown concerts and her 2002 recording “Paganini: After a Dream,” which she made in Genoa, Italy, as the first jazz musician and African American to play the 1743 Guarneri violin of Niccolò Paganini. Four years later, she received a $500,000 fellowship, known as a “genius grant,” from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The funds have enabled Carter to pursue another long-held dream — to explore music of Africa and the African Diaspora. She said of the project, “There is an immense amount of amazing music coming from all around the world, much of which is barely accessible. ‘Reverse Thread’ gave me the opportunity to explore and celebrate a tiny portion of music that moved me.”

Like the blues-inflected vein of jazz that remains Carter’s point of departure, folk music gains its power to affirm and console by making room for life in all of its hardships and joys. Songs that are passed from one generation to another remind us that no matter how bad things get, we are not alone. Others have been there too.

Using simple, sturdy melodies and rhythms, the songs express a variety of human experiences: lost love, mortality, celebration, surviving a storm or drought and the endurance of friendship, family and community. Humor, anger and exultation are often contained in the same piece of music.

Performing with most of the musicians who accompanied her on the CD, the 90-minute set drew from the album, which includes folk melodies of Senegal, Mali and Uganda as well as songs by contemporary African musicians.

Accompanying Carter were her long-time sidemen — accordionist Will Holshouser, bassist Chris Lightcap and Alvester Garnett on drums and percussion — along with Yacouba Sissoko of Mali, a master player of the kora, a West African harp.

Carter introduced the players as “my family” and the tightness and precision of their interplay and the pleasure with which they performed together attested to their closeness as a group. They were a family that relished each other’s individuality and harmonized into a sublime whole.

The intimate club setting suited the ensemble, which had the feeling of a chamber group led by the warm and gracious Carter, who presided and played with serene authority and joy.

Generating voluptuous emotion through musicianship characterized by formal clarity and restraint, the players were faithful to the apparent melodic and rhythmic simplicity of the folk melodies. The uncrowded arrangements made room for the music to expand at the hands of the musicians into impassioned solos, duos and blends that plumbed the story within the song and followed its original thread without losing it.

Watching the players manipulate instruments that are not everyday tools of a jazz ensemble was part of the fun — from Holshouser’s Italian accordion with its glittering art-deco grill (“It’s really just sparkly foil,” he wrote in an e-mail) to Sissoko’s long-necked kora.

Attired in a dark blue dashiki, Sissoko sat on a low stool to cradle his kora and pluck its 21 strings with his long, slender fingers, creating dulcimer-like sounds that varied from percussive to lyrically melodic (at one point evoking rippling water). His grandfather taught him how to play the kora, he told the audience, and he built his instrument in the traditional way. He covered a large gourd with cow-hide to make its base and used fishing line for its strings.

Only an acoustic bassist as inventive and agile as Chris Lightcap could meet the challenge of providing a pulsing axis to the music while adding subtle tonal color and joining the violin and kora in melodic and rhythmic variations that often unfolded as much like chamber music as jazz.

The bass, violin and kora intertwined with richly textured and delicate percussive accompaniment by drummer Garnett and the chimera-like voice of Holshouser’s accordion, which varied from a low drone to a high pitch in contemplative, plaintive passages of “N’Teri,” a song by Habib Koité of Mali that Carter said was about friendship. She described another meditative piece, “Kothbiro,” by Ayub Ogada of Kenya, as “a prayer for rain.”

Introducing “Hiwumbe Awumba,” a traditional song that she unearthed in the recordings of a Ugandan Jewish community, Carter said that she was surprised to learn that in translation its title said, “God creates and then He destroys.” “I thought it was happy and joyful music,” she told the audience. “But what I think it means is, that we should enjoy life today. None of us is getting out of here alive.”

The group opened each song by playing its core melody and rhythm, often a solo or duo that conveyed the raw flavor or quiet lyricism of the original. Then they traded parts and unraveled the song, mining its harmonies, rhythms and textures before returning to its core.

As Holshouser introduced his arrangement of “Zerapiky,” a traditional vocal-and-accordion piece from Madagascar, he held up an MP3 player and let the audience hear part of the original recording, with its spare, punchy chants and chords. Then the group took it to a rousing, danceable high with whirling violin and accordion.

Like the album, the performance included contemporary music of the African Diaspora as well as traditional songs. The ensemble played Garnett’s composition “New for New Orleans,” a celebration of post-Katrina rebirth woven from whirling shards of music, including the familiar cadences of second-line march riffs. Playing with muscle and abandon, a radiant Garnett unleashed a cascade of rhythmic complexity in his raucous and cathartic solo.

Another song that gave full voice to pain and released its hold was “Kanou,” a compositon by Boubacar Traoré of Mali based on a folk melody of India. Its lyrics, said Carter, are the words of a spurned lover, who tells the woman, “Even if I changed myself into diamonds and gold, you still wouldn’t love me.”

Playing an arrangement written for Carter by jazz pianist and composer Gil Goldstein, the ensemble began the song as an infectious, upbeat country jig. As Holshouser’s accordion took on a low raga-like drone to Garnett’s intricate drumming, they slowly brought the song to a crescendo of fury and fire and then, as if emerging from a great storm, they returned to the lilting jig.

As for the next leg of Carter’s musical journey, she has said that “Reverse Thread” is only the start. She will continue to explore old and new songs and follow a thread that leads her further into Africa.