WASHINGTON — The comic book superheroes of Dwayne McDuffie’s childhood were all tights and flights, blond hair blowing in the breeze, blue eyes twinkling from behind a mask.

The few black characters that existed then were cast as foreign-born, or former thugs, or criminals who changed their ways. One company even thought the “Black Bomber,” a white racist who would turn into a black superhero when under stress, was a good idea.

Today, the worlds where the battles for truth, justice and the American way are fought are chock full of superheroes of all ethnicities and genders. This is due in large part to McDuffie, who championed diversity during a comic, animation and television writing career that spanned more than 20 years.

The sudden death of McDuffie last week at age 49 has sent comics aficionados, as well as the multimillion-dollar comics industry, reeling.

McDuffie was just beginning to crack the Hollywood market, writing animated movies for DC Comics and spearheading popular TV cartoon series. His animated movie adaptation of the comic book series “All-Star Superman” premiered two weeks ago.

“He was an incredibly successful writer and editor of comic books. And this is regardless of color,” said film director Reginald Hudlin, a friend of about 15 years. “He had success both with black characters and some of the biggest, most mainstream characters.”

While prolific in his writing — his credits include stories about Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four and the Justice League, cartoon characters such as Ben 10 and Scooby Doo, and movies such as the new animated “All-Star Superman” — McDuffie’s enduring legacy is as a founder and editor-in-chief of Milestone Media, the first major comic book imprint to feature non-white lead characters.

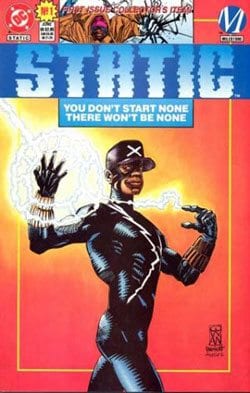

Under McDuffie’s leadership, the eponymous Hardware and Static were black. “Xombi” was Korean American. “Kobalt” was white. Heroes of every race, creed, color and sexual orientation populated the “Blood Syndicate,” “Heroes” and the “Shadow Cabinet.”

“Milestone was the shared vision that we would provide the world with images that had been excluded from the mainstream for decades. Dwayne was the key to making that dream a reality to our company and comic book fans, as well as those who sought tales of adventure,” Derek Dingle, who co-founded Milestone with McDuffie, told Comic Book Resources.

“Dwayne realized the importance of creating such images because they represented heroes and opportunities,” Dingle said. “He also saw comic books and animation as a way of dealing with such issues as racism, sexism, gang violence, gun control and conflict resolution without sacrificing entertainment value.”

McDuffie often said he didn’t set out to be a black comic writer, or a comic-book writer who wrote about black issues. But he didn’t run from those roles either.

“I’m conscious of race whenever I’m writing, just as I’m conscious of class, religion, human psychology, politics — everything that makes up the human experience. I don’t think I can do a good job if I’m not paying attention to what’s meaningful to people, and in American culture, there isn’t anything that informs human interaction more than the idea of race,” McDuffie told The Atlantic in a March 2010 interview.

Milestone was so revolutionary because the mass comic book market had never seen so many multicultural characters before. McDuffie, a lifelong comic book fan, was keenly aware of the lack of superheroes that looked like him.

“You only had two types of characters available for children,” McDuffie told The New York Times in 1993. “You had the stupid angry brute and the he’s-smart-but-he’s-black characters. And they were all colored either this Hershey-bar shade of brown, a sickly looking gray or purple. I’ve never seen anyone that’s gray or purple before in my life. There was no diversity and almost no accuracy among the characters of color at all.”

The first black character to headline his own comic book was Dell Comics’ Western hero and gunfighter Lobo in 1965, whose series sold poorly and was canceled after two issues. Marvel introduced the world to comics’ first African American superhero, the Falcon, in 1969; Eventually, it was revealed that the hero’s alter-ego was a criminal who had been brainwashed into acting like a superhero. The Black Panther, who had been introduced as a supporting character in Fantastic Four in 1966, was actually an African king, not an American.

The self-titled comic book “Luke Cage, Hero for Hire” debuted in 1972, featuring a “Blaxploitation” character with an exaggerated Afro, a catchphrase “Sweet Christmas!” and super strength as the result of a prison experiment, an archetype that would be repeated often in comics. McDuffie and Milestone helped to change all that.

In a 2009 interview with Mania.com, McDuffie said his goal was to “portray a fictional world that looked like the real world.”

“A big part of it was creating characters from a wide-range of backgrounds — ethnic, religion, class,” he said. “Usually, heroes are white, middle-class males or upper class males like Batman. This made sense in the 1940s and 1950s, but it didn’t represent the world very well (in the 1990s), nor did it represent the audience very well.”

Milestone started an exciting new phase for comics, said comic book historian and author William H. Foster III. It proved that well-written stories about multicultural, diverse characters would sell, a point underscored when DC Comics agreed to distribute their work nationwide, Foster said.

“They did a hell of a job, but never gave up their Afrocentric identity,” Foster said. “(For) anybody who wants to start a comic book or who is a person of color, Dwayne McDuffie has blazed an amazing trail.”

The Milestone imprint didn’t last long but the influence on the rest of the industry is undeniable.

Milestone comics led to the television series “Static Shock,” one of the few cartoon series ever to feature a black teenager as its titular hero. DC Comics recently integrated Static and the rest of Milestone’s characters into the universes of Batman and Superman.

Recently, Archie Comics (Archie, Jughead, Betty and Veronica), introduced an openly gay character named Kevin. DC Comics, the home of Superman, Wonder Woman and Batman, introduced a Jewish lesbian heroine, Batwoman, in recent years.

And The Walt Disney Co., which purchased Marvel Entertainment and its comic characters such as Spider-Man, the Hulk and Iron Man in 2009, introduced its first African American princess, Tiana, in its animated movie “The Princess and the Frog,” that same year.

One of the most popular characters to come out of DC Comics’ animated “Justice League” cartoon, which McDuffie helped write, was John Stewart, a black Green Lantern. This is despite early complaints that Stewart was chosen for the cartoon instead of the white Hal Jordan, who is being featured in the live-action “Green Lantern” movie later this year.

“This summer, when ‘Green Lantern’ comes out, there’s going to be a whole generation of kids who walk into the theater and say, ‘That’s not the Green Lantern; the Green Lantern is John Stewart.’ And that’s because of Dwayne,” writer Kevin Rubio said at a tribute to McDuffie this week, according to Comic Book Resources.

Such a rapid change in attitudes was possible because McDuffie never forgot the history behind the comics he read as a child.

In 1977, DC Comics was talked out of publishing the Black Bomber by Tony Isabella, who replaced Bomber three weeks later with Black Lightning, a schoolteacher who gains electrical powers and becomes a superhero.

Thirty-one years later, in one of the last “Justice League of America” issues he wrote, McDuffie slipped in a throwaway character called the Brown Bomber — a white guy who turned into a black superhero with a super-sized Afro.

Associated Press