On the cold November night when President-elect Barack Obama declared victory, black America appeared perfectly unified. The vast majority of African Americans had supported Obama throughout his presidential bid, and in his election, the dreams of the Civil Rights Movement had finally been fulfilled.

But is black America really as monolithic as this single evening suggested? Pulitzer Prize-winning author Eugene Robinson says no — by the time America elected its first black president, black America no longer existed, Robinson argues.

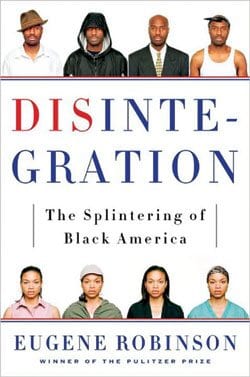

In “Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America,” Washington Post veteran Eugene Robinson contends that black America is a thing of the past — instead, four distinct groups of black Americans have taken its place. Surveying African Americans just 46 years after the passage of the monumental Voting Rights Act of 1965, Robinson concludes, “The fact is that asking what something called ‘black America’ thinks, feels, or wants makes as much sense as commissioning a new Gallup poll of the Ottoman Empire. Black America, as we knew it, is history.”

Drawing upon personal experience and 30 years of reporting at the Washington Post, Robinson argues that since the victories of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, black America has splintered into a middle-class “Mainstream” majority; a large impoverished, “Abandoned” minority; a tiny “Transcendent” elite; and an “Emergent” group of immigrants and multi-racials.

This fragmentation, while not “something black America likes to talk about,” is substantiated by census data, economic statistics, and housing patterns, he says. And although the African American community has always been diverse, according to Robinson, disintegration today means that “more and more … we lead separate lives.”

Robinson, a South Carolina native who grew up during the Jim Crow era, argues that disintegration began after the passage of civil rights legislation, when African Americans suddenly gained access to better jobs, schools and housing. With these new opportunities, the majority of African Americans soared up the social ladder to stable, middle-class lives. Blacks’ “heroic” ascent to the middle-class in the latter half of the 20th century, Robinson says, “is truly a great American success story — arguably, the greatest of all.”

In less than 40 years, the percentage of African Americans earning more than $35,000 in today’s dollars expanded by 20 percent — a boom from 25.8 percent to 45.3. In the same time period, the proportion of black households earning more than $75,000 jumped from 3.4 percent to 15.7, according to census statistics Robinson cites.

And some climbed even higher, reaching a transcendent status of power and wealth that “even white folks have to genuflect,” he says, like Oprah Winfrey, Barack Obama, Tiger Woods and Jay-Z.

At the same time, a large number of African Americans were left behind. As the upwardly-mobile fled the old segregated communities for integrated neighborhoods and schools, the ones who were not wealthy enough to do so remained. In addition, the manufacturing jobs that was once the bulk of black employment swiftly moved overseas where wages were cheaper, leaving many blacks in search of steady work. Schools and businesses faltered, says Robinson, leaving a vacuum into which “undesirable pathology — poverty, teen pregnancy, single motherhood, drugs, crime, growing isolation from the mainstream” came rushing in.

According to more census statistics cited in Robinson’s book, these poor are in a downward spiral. In 2000, 14.9 percent of black households brought in less than $10,000, but by 2005, this group grew to 17.1 percent. During the Jim Crow era, black neighborhoods were racially segregated but economically and socially integrated. Now, these same neighborhoods are segregated “in all three senses — black, poor, isolated.”

As the descendents of African slaves endured these rapid economic and social changes, changes to immigration policy in 1965, 1976 and 1980 opened the way for immigrants from Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Haiti and other sub-Saharan African and Caribbean nations. Around the same time, anti-miscegenation laws were abolished, making white-black unions legal, and increasing the number of bi-racial Americans. These two emergent groups, Robinson says, “make us wonder what ‘black’ is even supposed to mean.”

While Robinson documents the fragmentation of black America, he is sure to say that disintegration doesn’t have to mean disunity. “What I’m trying to do here is not to draw lines — I’m just trying to see things clearly so we can work on the right problems in the right way,” he told talk-show host Tavis Smiley.

And for Robinson, those “problems” are primarily with the abandoned. “They’ve been abandoned by everybody,” he said in the same interview. “They’ve been abandoned by the government, they’ve been abandoned by the transcendent black folks, and they’ve been abandoned by, increasingly, the mainstream black folks.”

In addition to being pushed to the physical peripheries of the cities, the abandoned have been pushed to the “periphery of our national consciousness.”

“We want to pretend that we’re all unified and that we’re all one, and that we’re all still holding hands,” Robinson continued. “I think we just need to look critically, and we need to look honestly at what’s really going on.”

Because, he explained, the abandoned are slipping further and further from the mainstream. “The distance is growing — the distance isn’t shrinking in the way it’s supposed to be shrinking,” he said. “And until we recognize that I think we’re not going to get done what we need to get done, which is concentrated effort to help the abandoned before it’s too late.”