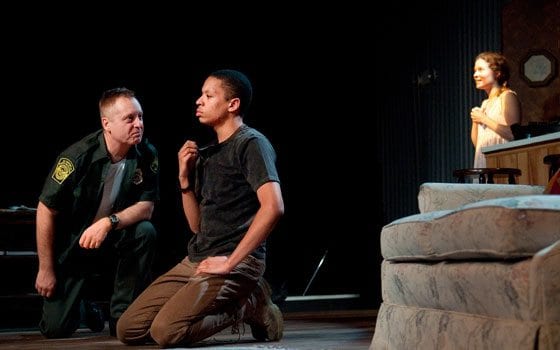

Author: Liza VollJesse Tolbert (Buddy), Steve Barkhimer (Vet) and Frances Idlebrook (Grace) star in Company One’s production of “Book of Grace,” which is showing at the Boston Center for the Arts Plaza Theatre through May 7. The play, chronicled by Vet’s wife Grace, focuses on Buddy’s return from military service and the tumultuous relationship between him and his father Vet.

Suzan-Lori Parks is a writer determined to make large statements about American life. This was all to the good with her Abraham Lincoln-championing and racism-decrying, Pulitzer Prize-winning drama “Topdog/ Underdog.”

In that riveting drama, the conflict between two brothers had the kind of visceral power and rich characterization that Edward Albee brought to George and Martha in his large statement masterpiece ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” She means to do the same in her recent Off-Broadway play “The Book of Grace,” though the characters sometimes seem more prototypical than fully developed. Even so, Company One — thanks to a strong effort by guest director David Wheeler and a first rate acting trio — makes this New England premiere compelling.

Set in a South Texas home right at America’s border with Mexico, “The Book of Grace” focuses on the perilous homecoming of a young bronze medal-honored soldier named Buddy and the ups and downs of his reunion with his macho border patrol father, Vet.

Chronicling that reunion with an almost surreal optimism is Vet’s new wife Grace. Grace, a diner waitress who has been compiling upbeat stories with newspaper clippings and photographs, sees her collection as “the evidence of good things.” Despite ample evidence of bad blood between Buddy and Vet, she remains hopeful that all three can live a life of understanding and attain a wonderful future together.

That rosy scenario looks to be a fantasy at best. Vet turns a father-son hug into a pat-down for possible weapons rather than a warm family greeting. Is part of the tension between them tied to the fact that Buddy is the product of a white father and an African American mother? Vet, who is soon to be honored for catching drug-carrying illegal immigrants during his work at the border, is clearly bigoted toward Mexicans and speaks in polarizing terms of “them” and “us.”

He also appears to minimize Buddy’s honored military service and to question his future as part of their family — and by extension the family that is America. Vet may not identify as a “birther,” but his largely hostile attitude toward Buddy may call to mind the ongoing racist assertion by many Americans that President Barack Obama was not born in Hawaii. Not surprisingly, Vet contends — much as Tea Party members often do — that “sometimes the alien is at home.”

As Buddy’s search for acceptance, genuine paternal love and an apology for previous mistreatment meets with rejection and new defiance from Vet, the son’s response threatens to become a totally vindictive one. Can Grace mediate the tension between them? Will her kindness and positive thinking lead her husband and stepson to the domestic tranquility that Buddy quotes from the Founding Fathers as a kind of personal credo? Do the holes Vet has dug in the back yard — one at the time of the play and one at the time of his late first wife in the back story — connect to a philosophy of violence that Buddy will not be able to overcome?

All of these are worthy questions that Parks tries to tackle in this provocative and timely yet overly busy drama. At the same time, “The Book of Grace” lacks the nuance and that helped to make “Topdog/ Underdog” a taut and more fully realized work.

Still, actors’ director Wheeler (with the assistant direction of his actor son Lewis) makes the scenes of the play — structured as chapters in Grace’s on-going commitment to good things in life — absorbing from start to finish.

Steve Barkhimer catches the seething volatility in Vet but never overplays it; the result is a truly scary portrait of a bitter individual and disgruntled prototype. Jess Tolbert delineates Buddy’s remarkable warmth, profound hurt and wounded integrity with the right combination of alternating energy and pathos. Equally affecting and memorable is Frances Idlebrook’s appealing evocation of Grace’s optimism and enormous heart even in the face of Vet’s unrelenting meanness.

A fine design team brings poetic reinforcement to the play’s disturbing tableau of confrontation and despair. Eric Diaz’s stark but well-detailed family set works well with Jason Weber’s border and Texas projections. Kenneth Helvig’s subtle lighting and David Wilson’s sharp sound work complete a design quartet that actually covers at times for the overly programmatic qualities of the play.

There are always good things in a Suzan-Lori Parks play. The evidence in “The Book of Grace,” though, sometimes comes more from Wheeler’s painstaking direction and a crack Company One ensemble than from this essential dramatist’s over-written text.