Ghanian-born artist El Anatsui is known for making gorgeous tapestries from liquor bottle wrappers

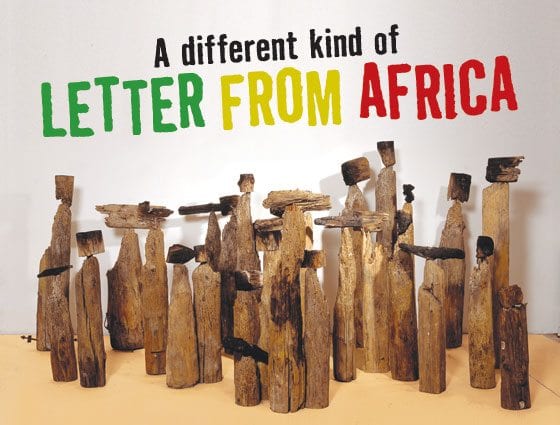

Author: Jack Shainman Gallery“Akua’s Surviving Children” (1996) Wood and metal, dimensions variable.

Author: Museum for African Art, Kelechi Amadi-Obi“Akua’s Surviving Children” (1996) Wood and metal, dimensions variable.

Ghanian-born artist El Anatsui is known for making gorgeous tapestries from liquor bottle wrappers

As warm and engaging as its title, the exhibition “El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa” — on view through June 26 at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum and Cultural Center — is one of the most memorable museum shows in Greater Boston this year.

Ghanaian-born El Anatsui, now based in Nigeria, has recently gained renown for shimmering sculptures made from thousands of discarded Nigerian liquor-bottle wrappers. But as this retrospective spanning four decades demonstrates, his earlier works in wood and ceramic are also rich in grandeur and surprise.

Regarded as the most important African sculptor working today, Anatsui raised his international profile at the 2007 Venice Biennale when one of his lustrous tapestries of bottle wrappers draped the façade of a palazzo on the Grand Canal, creating a sensuous and moving image of memory and loss.

Long revered in Africa, Anatsui, 67, has only in the past decade gained international fame. From 1975 to 2010, he taught sculpture at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where in 1976, at age 32, he presented his first solo show. Four years later, at the Cummington Community of Arts in Massachusetts, he held his first solo show outside Africa.

Anatsui’s works are now exhibited and collected by major museums in 25 countries. This exhibition, however, is his first major retrospective and Davis is hosting its U.S. premiere. Curated by Lisa Binder of the Museum for African Art and organized by the museum, which is in New York City, the retrospective will be an inaugural exhibition of its new building, which opens in fall 2011. Binder also edited the richly illustrated catalog that accompanies the exhibition.

Occupying two floors of the Davis, the exhibition presents about 60 works by Anatsui since the mid-70s, including sculptures in wood, ceramic and metal as well as paintings and drawings exhibited for the first time outside of Nigeria.

The sleek, spare environment of the Davis, designed by the great Spanish architect José Rafael Moneo, offers a luminous setting for Anatsui’s works, which exert immediate impact with their drama, sensuous allure and humor yet also reward unhurried contemplation.

While continuing to compose his works from the materials of nature and daily life in Africa, Anatsui has evolved his process and methods over four decades. At first, he used hand tools to chop, carve, scorch and etch wood; but in the ‘90s he began carving jagged rifts into blocks of wood with a power saw, evoking the ruptures of Africa wrought by the slave trade and colonization. Then he turned to discarded trash and other found objects as raw materials rich in associations. Formerly working solo, Anatsui has developed a team of assistants as his projects have expanded in scale.

Anatsui’s glittering tapestries of liquor wrappers adorn the walls of the ground level gallery. The intricately woven grids evoke the patterns of kente cloth, a traditional textile of Ghana. Their corrugated metallic folds glint in the light, three-dimensional mosaics that call to mind the geometric gold-leaf patterns of paintings by Austrian modernist Gustav Klimt (1862-1918). With shimmering folds and brilliant colors, some resemble topographical maps. Others memorialize places or shared cultures and histories.

Equally riveting are two works that spread over the gallery floor. “Open(ing) Market” (2004) both celebrates the burgeoning African marketplace and wryly comments on Africa’s part in the global economy. A sea of miniature tin chests forms the shape of the Africa. Made by local tinkers in Nsukka, the black chests are arranged in rows and when viewed from the rear, the installation gels into dark waves. Seen from the front, the boxes burst with color, their insides lined with ads for international brands such as Nestlé.

Despite its title, “Digital River” (2001) — a stream of narrow clay vessels filled with dark, glistening glass, calls to mind a train bearing minerals, Africa’s primary export.

A trio of sculptures introduces Anatsui’s eloquence with wood. Reminiscent of the abstract patterns in the wall hangings is “Wonder Masquerade” (1990), an elegant totem of sliced bronze wood incised with lines and hewn into a graceful ellipse. Next to it is a pair of rough-hewn figures: a scarecrow-like structure with branches for legs, “Lady in Frenzy” (1999) and a tin man with a tiny wood stump for a head, “Chief in Zingliwu” (1999).

Titles matter to Anatsui, a poet who uses language as another raw material to interweave eras, places and histories.

The jazzy, statuesque “Adinsibuli Stood Tall” (1995) has a title that blends the names of three African writing systems: Adinkra, Nsibidi and Uli. Composed of discarded wooden mortars used to extract palm oil, a Nigerian staple, its body resembles a hollowed-out tree trunk. On the outside, the wood’s grooves and veins evoke ancient Chinese landscape scrolls. Inside, Anatsui has painted African ideograms of suns and organic forms that resemble cave paintings or American Indian pictographs. Wires that suggest ornamental necklaces fasten the figure’s head, a craggy piece of wood.

On the fifth floor, the museum’s magnificent 5th century stone mosaic from the Villa of Daphne, near Antioch, Turkey, echoes the classical grandeur of Anatsui’s weavings. This gallery displays Anatsui’s works on paper as well as free standing sculptures and small works in ceramic and manganese, a mineral that is among Africa’s primary exports.

Many works tell stories. “Akua’s Surviving Children” (1996), a colony of figures constructed from scorched, pocked driftwood gathered on Denmark’s shores, alludes to the Danish slave trade. Their parts are joined with nails forged at a factory that made guns for slave runners. Anatsui burned the heads in the forge as a purification ritual.

An abacus-like wooden plaque, “Old Cloth Series” (1993) blackened to show wear and age, is carved and painted with patterns reminiscent of Ghana’s fabric of memory, kente cloth. A work from 1986 that gives the exhibition its name has a long title that begins, “When I last wrote to you about Africa.” Horizontal slats of burled wood are fashioned into an unfolding scroll and incised with ideograms that evoke Ghanaian myths, nature and lineage.

Another gorgeous work, “Assorted Seeds II” (1989), combines eight deeply grained slats of wood in varied tones into a visual creation myth, with the seeds carved out of its richly textured surface like a bas relief.

Displayed in vitrines are Anatsui’s works in ceramic and manganese, which has a speckled beige-and-black surface like old stone. The writhing “Imbroglio” (1979) combines skin-like layers and tangled loops in an image of tension. Clay tendrils wind over the egg-shaped form of “Omen” (1978), which also appears in one of the elegant pen-and-ink drawings that are on view. In some works, Anatsui intertwines shards that resemble fragments of western classical pottery, as if to conjure history across civilizations and eras.

When viewed from the rear, the sculpted head, “Chambers of Memory” (1977) is a skull with hollows occupied by small objects. On the reverse side is a faintly visible face, its eyes, nose and lips resembling the elegant terracotta heads of Nigeria’s ancient Nok culture. Like the exhibition as a whole, the sculpture connects past and present, bringing old and new together into a richer, more universal story.

The Davis Museum and Cultural Center is on the Wellesley College campus in Wellesley, Mass. Admission is free and open to the public.