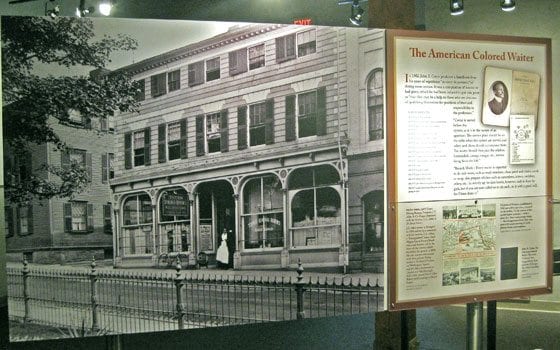

Author: Culinary Arts MuseumJohn B. Goins, “The American Colored Waiter.” (Chicago: The Hotel Monthly, 1902.) Book on display from the collection of Robb Dimmick. Touro Dining Rooms, Newport. J.T. Allen and Co. Props.

A unique exhibit showcases the long history of cooking by African Americans

Rusted leg irons worn by slaves during the Middle Passage and a silver spoon honoring abolitionist and civil rights crusader Frederick Douglass are part of a small but stirring exhibition at the Culinary Arts Museum in Providence.

Entitled “Creative Survival: African American Foodways in Rhode Island,” the exhibition tells the story of African American cookery in the state from the 1700s to the present day. Artifacts, memorabilia, photographs and testimonials showcase the ingenuity of African Americans who cooked and served food as slaves and then, as newly freed men and women, became successful entrepreneurs in culinary trades.

Arriving in the ports of Newport and Providence, slaves learned to cook with the leftovers or scraps of their owners’ kitchens. By the 1850s, when slavery was abolished in Rhode Island, they used their skills as cooks and servants to earn a livelihood.

A 1726 bill of sale records the purchase of two Africans in Newport for 21 barrels of cider and a few dollars. Nearby are stories of slaves esteemed for their culinary talents. A woman named Phillis perfected Rhode Island’s iconic jonnycake. Celebrated pastry chef Charity “Duchess” Quamino of Newport served her delicacies to George Washington. In 1736, freed slave Emmanuel Manna Bernoon opened the first restaurant in Providence.

The exhibit’s 19th century highlights include an 1879 photo of May Johnson, a domestic who at age 74 was a youthful and elegant-looking woman. The caption states, “49 years and still a faithful servant in the family of Mr. Cr. N. Talbot.” Nearby is an 1882 photo of Thomas Moke, a popular fruit vendor on the Brown University campus.

As Irish immigrants began taking over jobs in wealthy white households, African Americans turned to the railroad for employment. One poster shows the resourceful John B. Goins, who shared his expertise as a headwaiter in a 1902 handbook of dining car service dos and don’ts.

Dominating this gallery of enterprising African Americans is George T. Downing (1819-1903). His father Thomas ran an oyster house on Wall Street that served such patrons as Charles Dickens and Queen Victoria. Like his father, George was masterful at transforming oysters, then a poor man’s food, into gourmet fare for wealthy palates. After opening his own restaurant in New York, he created a five-story resort in Newport and for 12 years presided over the dining room of the House of Representatives in the US Capitol.

In 1895, African American inventors William H. Purdy and Leonard C. Peters of Providence patented their design of a sterling silver spoon honoring Frederick Douglass. The exhibit presents the only known replica of their design. Incised on the spoon’s ladle is a picture of a boy by a log cabin. On its finial is a formal portrait of Douglass. Running along the handle and connecting the two images is a ladder, signifying an achiever’s ascent.

In a video interview, Jefferson Evans, 88, tells of his journey from rural poverty to prominence. The first African American graduate of the school that became the Culinary Institute of America, he ran his own restaurant in New Haven in the 1980s. Although he had learned French culinary techniques, as a chef he practiced the traditional Southern cooking of his childhood.

Another African American who has thrived on family cooking traditions is Norma Jean Darden. Her catering business and two soul food eateries in Harlem draw a clientele that includes former President Bill Clinton, Angela Bassett, Mike Tyson and Vanessa Williams. At last Wednesday’s opening of the exhibition, Darden spoke to a standing-room audience about the book she co-authored with her sister Carole, “Spoonbread and Strawberry Wine: Recipes and Reminiscences of a Family.”

On view through March 4, “Creative Survival” is a project of Providence historians and rare-book dealers Ray Rickman and Robb Dimmick. They developed the exhibition with Richard Gutman, the director and curator of the museum, which is part of Johnson and Wales University.

Following Darden’s recipes, student chefs who are members of the Johnson and Wales chapter of the Harlem-based Bridging Culinary Arts organization cooked and served biscuits, gumbo and braised goose.

Food will again accompany the exhibition on Feb. 2 at 5:30 p.m. when local African American chefs will conduct cooking demonstrations. “When you come to the exhibition, sign our guest book,” said Gutman, “and we’ll send you an invitation.”

Also luring visitors are the museum’s vintage dining environments, complete with blazing neon signage. Looming like stage sets, the reconstructed originals include an Art Deco mahogany bar from the Prohibition Era and an 1830s taproom. Gutman’s labor of love, a gallery of diners, includes parts of a state fair midway, a child-size replica of a diner and the 1930s-era Ever Ready Diner, hauled from downtown and under restoration in the gallery.

Lingering before the portraits in “Creative Survival,” Darden was captivated by the stories on view. “I wish this exhibit could travel,” said the former Wilhelmina model, statuesque and striking in a striped, off-shoulder jersey and long, lacey skirt. “I’ve never seen this brought to life —the story of food going back to slavery and early entrepreneurs, how people survived. These are things we knew, but seldom see brought to life.”

When her modeling career came to an end, Darden too found a livelihood in culinary arts. “Food is fashion and fabric on a plate. Like these gentlemen, we all have to keep evolving.”

The Culinary Arts Museum is located at 315 Harborside Blvd., Providence, R.I.

The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.