Will Allen’s life proves that success often grows from failure. The six-foot-seven Maryland native spent his youth dreaming of playing in the NBA. After being drafted to the Baltimore Bullets (now the Washington Wizards) and becoming the leading scorer among rookies that year, Allen was cut just days before the 1971 season began.

After brief stints in the now-defunct American Basketball Association and a league in Belgium, Allen accepted that his childhood dream wouldn’t come true, and eventually turned to an unlikely profession — farming.

Allen, 63, now heads Growing Power, a three-acre urban farm in Milwaukee that provides more than 40 tons of fresh, local food a year to the city’s poor residents by harnessing innovative techniques such as vertical growing and indoor fishponds.

Allen quickly became one of the most recognized faces in America’s food revolution, and in 2008, was awarded the Mac-

Arthur Foundation’s prestigious “genius award” — making him the second working farmer to ever receive the honor.

“You’re going to have disappointments in life, but you need to recover quickly and move on to something else and not give up,” Allen said. “Being a farmer is much harder than being a professional basketball player. A successful farmer, anyway.”

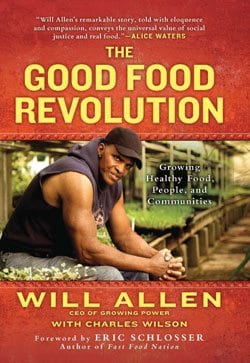

In his new book, “The Good Food Revolution: Growing Healthy Food, People, and Communities,” Allen chronicles his life and farming career, and makes the case for African Americans to return to their agricultural roots.

As was typical of their generation, Allen’s parents were Southern sharecroppers who moved north during the Great Migration. But unlike most of their contemporaries, Allen’s parents continued to farm alongside their day jobs, and passed on the knowledge — and love — of farming to their children.

“When many African Americans left the South and ventured north, they left behind their skills, not wanting to pass them on because of the harsh conditions they lived through,” Allen explained. “We have suffered through several generations of not passing on those farming skills. Farming is a very skilled occupation even though a lot of people think food just appears on the table; that it comes out of the air.”

But Allen didn’t always dream of becoming a farmer like his parents. After earning a basketball scholarship to the University of Miami, and 6 years of playing professionally but never quite making it to the NBA, Allen went in the opposite direction, and took an executive position with Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Even in the world of fast food, farming tugged at Allen’s heart, and he later started tilling a 100-acre farm. All that changed in 1993, when Allen, then working for Proctor and Gamble, spotted an abandoned greenhouse on the side of the road. Taking a chance, Allen cashed out his retirement to purchase the land, and Growing Power was born.

What started as a simple roadside fruit and vegetable stand — which earned Allen the nickname “the Gucci of greens” — soon grew. Allen began experimenting with several farming techniques, such as vertical growing, stacking rows of plants from floor to ceiling in the greenhouse to maximize space; vermicomposting, creating nutrient-rich soil with compost and worms; and aquaponics, simulating a freshwater river indoors to raise fish.

Just as important, Growing Power became an integral part of the community by offering jobs to low-income residents, training people in growing and cooking, hosting youth programs and selling food at an affordable rate. These community ties, Allen said, are what make urban farms sustainable.

Allen’s work was based on a simple, but radical belief: “I believe that equal access to healthy, affordable food should be a civil right — every bit as important as access to clean air, clean water, or the right to vote,” he writes in his book.

But initially, not everyone understood what he was doing. “Fifteen years ago, I would be in African American communities and people would ask me, ‘Why are you doing a slave’s work?’” Allen said.

Now, those criticisms have disappeared. “I don’t hear that anymore, I think because first lady Michelle Obama embraced growing food by putting the small garden on the White House lawn,” he explained. “As I travel around the country, I see more African American folks wanting to get back into growing food, and wanting to learn because they didn’t learn.”

Of course winning the “genius” award helped, too. “It really helped the movement and our organization,” Allen went on. “And as a person of color, I think it’s helped propel people. When I go to communities, they’re proud that I’m involved, because the movement was pretty much dominated by white folks from universities and organic farms for many, many years.”

Now, in addition to heading Growing Power in Milwaukee, Allen travels the country, teaching others how to start up their own urban farms.

Despite all that he has achieved, Allen insists his work is still in its “infancy stages.” And his goals are nothing small: “Less than 1 percent of food in cities is local, and I’d like that dynamic to change to 10 percent. That’ll have huge implications in terms of job creation and our health. It’s predicted that 42 percent of us will be obese by the year 2030, and we have to work on that so that statistic goes away.”