local12b.jpg

“What does freedom look like?”

For years, historian Barbara Krauthamer grappled with this question, digging through photographic collections in archives across the country looking for an answer.

Krauthamer, a professor at UMass Amherst, had researched slavery and emancipation before, but after stumbling across some photographs of enslaved people, she became particularly interested in the visual record of bondage and liberation.

Together with her friend and former colleague, Deborah Willis, a scholar of African American photography at New York University, Krauthamer pored over “thousands and thousands” of 19th-century images in museums, universities and public libraries.

The result of their research is the new book, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery, a stunning collection of nearly 150 photographs — many that have never been published before — that sheds light on how African Americans lived under slavery, during the Civil War and just after Emancipation.

As Krauthamer and Willis explain in their book, which was published to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, photography in the mid-1800s was frequently used for political purposes. Abolitionists used photography to challenge white supremacy and the institution of slavery, while defenders of slavery used it to advance their racist ideology.

The Harvard-trained zoologist Louis Agassiz, for example, commissioned a photographer in South Carolina to take studio portraits of enslaved Africans in the area.

“The women are forced to open their dresses and reveal their naked breasts,” Krauthamer explains. “They have their bodies on display as scientific specimens and also as highly sexualized objects.”

She also notes that slaveholders frequently had portraits made of enslaved women holding the master’s baby as a way to show off their wealth.

At the same time, black people were also taking advantage of new photographic technology to tell their own stories. Sojourner Truth went into a studio in Michigan to have a portrait made — and then sold these pictures as a way to support herself. Frederick Douglass also harnessed photography to portray himself as handsome, dignified, confident and stylish — combating the racist images of black people at the time.

“One of the things we wanted to emphasize in the book was the many ways in which black Americans were the architects of their own lives, their own history and the nation’s history,” says Krauthamer. “We wanted to emphasize black people’s agency and the important role they played in shaping what freedom meant legally, socially and politically in this country. Black people weren’t waiting to be free, but were shaping what it meant to be free Americans.”

One photograph, entitled “Two brothers-in-arms,” does just this. The image is a studio portrait from 1860-1870 of two men in Union Army uniforms, with their arms around each other’s shoulders. Krauthamer explains that even before the Emancipation Proclamation, black men were putting pressure on the federal government to allow them to enlist.

“One of the things I like about this image is that it shows that sense of community and camaraderie among black soldiers,” she says. “They were fighting not just for their own beliefs, not just for their country — but they were fighting for their families, for their relatives who were enslaved.”

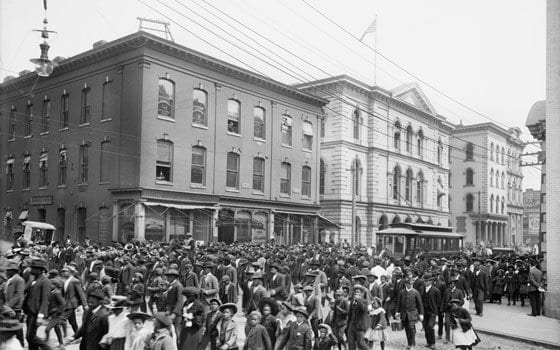

Another photograph, taken in 1905, shows a crowd of people dressed up, walking through the streets of Richmond, Va., to celebrate Emancipation Day. Krauthamer says these types of celebrations were common, and had been taking place ever since the 1830s, to mark the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies.

“This is a powerful image because it shows the ways in which black people were preserving history through collective gathering, and were also marking their presence on the American landscape,” she says. “Another thing that’s so powerful is that it’s 1905 — the moment when lynching and legalized segregation were taking hold across the country. What a powerful statement it would be for this community to claim the public space to commemorate the history of slavery and emancipation.”

After all of her work, Krauthamer says she has finally figured out what freedom looks like.

“Dignity, perseverance and hope,” she says. “Freedom for black Americans really looked like a sense of perseverance and dignity, and a commitment to family and community, even in the most trying circumstances.”