Ursula A. Matulonis, M.D.

Medical Director, Gynecologic Oncology

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Much progress has been made on the war on cancer. The Journal of the National Cancer Institute recently reported that death rates from all cancers combined are on the decline and improvements were evident in both men and women in all races and ethnicities. Yet, the 2012 report confirmed that the incidences of some HPV-related cancers are on the rise.

HPV, or human papillomavirus, is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that at any given time, roughly 20 million people are infected with HPV and another 6 million join the ranks each year.

It’s no wonder. There are more than 40 types of HPV that infect the genital areas of both males and females. Yet, most people remain unaware of these potentially lethal germs. Typically, HPV doesn’t have any symptoms, and its low-risk as well as high-risk strands are usually eradicated by antibodies found in healthy human immune systems.

But some high-risk HPVs, such as HPV 16 and HPV 18, can linger within a body and cause a myriad of cancers. Those two HPV strands account for 70 percent of cervical cancers but can be found in 40 percent of other genital cancers and almost all anal cancers. HPV 16 alone accounts for more than 50 percent of oral cancers.

The cause of the rise in HPV-linked cancers is not completely clear, but changes in sexual behavior have clearly played a part. According to the most recent Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, a survey conducted by the CDC, almost half of all U.S. high school students surveyed in 2011 said that they had had sexual intercourse, and more than 15 percent of these teens admitted to having sex with four or more people in their short lifetime.

The earlier in life sexual intercourse is started and the greater the number of sex partners, the greater the probability of infection and the greater the probability of a cancer-causing HPV strain.

Not surprisingly, smoking also plays a role and the combination of the two — smoking and HPV — packs a more dangerous wallop. Smokers who are afflicted with HPV 16 and HPV 18 are at increased risk for genital and oral cancers.

So significant is the impact of HPV in cervical cancer that in 2012, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists coupled HPV testing with Pap smears for women 30 to 65 years old as part of screening for cervical cancer. The objective is to identify high-risk HPV before it can do permanent damage.

Cervical cancer is more common in Latinas and blacks, but black women die of it at a greater rate than any other race. Although its incidence and death rates have plummeted since the inception of Pap smears, the American Cancer Society estimates that in 2013, more than 12,000 women will be afflicted with the disease and roughly 4,000 women will die.

It can take up to 20 years for the cancer to form, but it leaves tell-tale signs before it strikes. Fortunately, these differences are detectable under a microscope, which allows treatment for pre-cancerous lesions in the cervix. “The cells look different,” explained Dr. Ursula A. Matulonis, the medical director of Gynecologic Oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “They lose their features of what a normal cell should look like.”

If these changes persist, it is recommended for the individual to be followed by a gynecologist experienced in treating these conditions, advised Matulonis.

Correct and consistent condom use can reduce transmission but may not be 100 percent effective since HPV is transferred from skin to skin. The exposed areas — even when using condoms — are fair game.

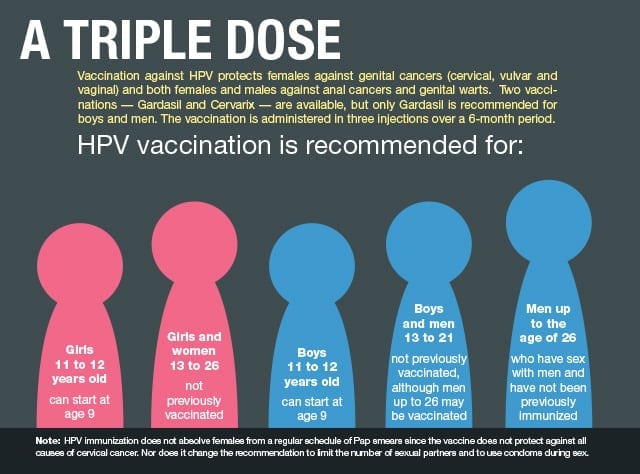

Vaccinations are ultimately the best answer. In 2006, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended HPV vaccination for females aged 11-12 and as young as nine. If not administered by the age of 12, catch-up vaccination is recommended for females aged 13-26. The vaccine is administered as a 3-dose series over a 6-month period.

In 2011, the ACIP extended this vaccination schedule to males. Two vaccines are available. Gardasil, manufactured by Merck and Co., Inc., protects against HPV 16 and 18 as well as the viruses that cause 90 percent of the cases of genital warts in both males and females.

Another vaccine, Cervarix, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline, protects against two of those subtypes, and is not recommended for males.

Although a vaccine has been in existence for six years, immunization rates in this country still remain low. The National Immunization Survey-Teen of 2011 found that nationwide, only a third of adolescent girls aged 13-17 years had received the three recommended doses. Sadly, the lowest vaccination rates are found in minorities, who have a higher incidence and death rate from HPV-caused cancers.

The reasons for non-compliance are varied. Because of the relative newness of the vaccination and doubts about its safety, parents are not flocking to their pediatricians to obtain the three shots for their children. Some parents also believe that protection brings with it the license for sex.

One study published recently in Pediatrics disputed that theory. The researchers followed 11- to 12-year-old girls for three years after HPV vaccination and looked for clinical markers of sexual activity, such as sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy and contraceptive counseling. They found that sexual behavior in the vaccinated group did not differ significantly from those girls who were not vaccinated.

A recent study at Boston University School of Medicine found that although a high percentage of parents interviewed were knowledgeable about HPV and its consequences, they still were slow to have their children vaccinated. Some parents preferred to leave the decision to their children when they reached adulthood.

A lack of state mandates is also to blame. Even Massachusetts has fallen short in this area despite leading the nation in other immunization rates. Only half the females had completed the three-dose recommendation for HPV, while the rates for tetanus and hepatitis exceeded 90 percent.

To date, only Virginia and Washington, D.C. mandate HPV vaccination for school attendance.

This apparent nonchalance toward the HPV vaccination will limit its impact in this country, Matulonis argues. “A high percentage of the population has to be vaccinated in order to achieve a herd effect,” she said.

Herd immunity occurs when a significant portion of the population provides some protection for unvaccinated persons. It is this herd immunity that eventually wiped out smallpox.

The HPV vaccine is relatively new and only recently was extended to males, but Matulonis is keeping a positive attitude. “We have to follow the group of immunized people over time,” she said.

State-mandated or not, vaccines remain an option. But Matulonis adds a word of caution. “In order for the vaccine to have a chance to protect against HPV infection, it must be given to an individual before their first sexual intercourse encounter,” she advised. “The vaccine cannot help people who are already infected with high-risk HPV.”