Black History Month is the time every year to learn more about the travails of the descendants of the Africans brought to America centuries ago. It is the story of an unrelenting drive for freedom, justice and equality. In addition to honoring the commitment and heroism of African American forbearers and their allies, it is also important for readers to assess that history to determine what errors were made and what other strategies might have been more effective.

Enthusiasm in the effort to obtain equal rights was intensified by the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Not only did it end the legitimacy of segregated public schools, but it also ended the doctrine of “separate but equal,” the basis for racial segregation since the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

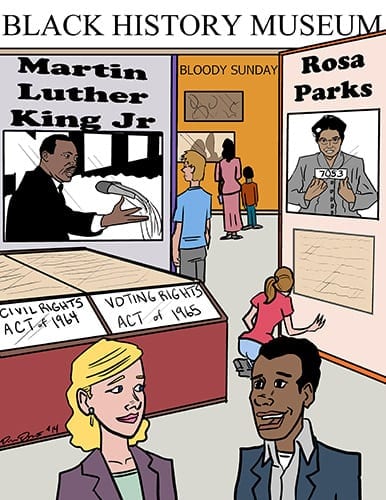

The Montgomery Bus Boycott began the next year, and the leadership of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. emerged. For a whole year, from Dec. 5, 1955 until the campaign ended victoriously on Dec. 21, 1956, blacks in Montgomery refused to ride the buses.

The Civil Rights Act that became law in 1957 was a disappointment to most people. After the glorious success in Montgomery people expected much more. The primary function of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was merely to establish a Civil Rights Division within the Justice Department. The purpose of the division was to develop legislative proposals to end discrimination and to mobilize a prosecutorial effort to enforce anti-discrimination laws.

Such a process was especially needed to assure black voting rights. A federal case in Forrest County, Miss., filed against the election registrar established the strategy for prosecuting violations of voting rights. The population of the county was 30 percent black but only 12 black citizens had survived the rigors of the registration process.

The battle over voting rights came to a head on March 7, 1965, “Bloody Sunday,” on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala. The police viciously attacked a group of peaceful protesters marching to Montgomery. They were attacked with tear gas, dogs and club-wielding police officers. Global publicity was embarrassing to America, the international paragon of democracy. President Lyndon Johnson called for a Voting Rights Act that Congress passed promptly. It became effective on Aug. 6, 1965.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (July 2) paved the way for the Voting Rights Act the following year. It made racial discrimination in education, employment and places of public accommodation unlawful anywhere in the country. For his effort in passing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Johnson got 94 percent of the black vote. The Republicans have never recovered from Barry Goldwater’s opposition to civil rights.

The strategy of the Civil Rights Movement was brilliant from the Brown decision in 1954 until the Voting Rights Act in 1965. But now, 48 years later in 2014, many African Americans would assert that the economic progress has been deficient. Perhaps after so many decades of struggle, fatigue has set in to diminish commitment to the battles that lay ahead.

Unfortunately, many blacks defined the racial problem as defective human relations when it has always been a battle for economic dominance. Black leaders have to understand that the major issue of civil rights has been overcome and the struggle now is to prepare for a highly productive role in society.