The New Economy Coalition’s CommonBound conference this past weekend brought 500 activists, academics and change advocates to Boston for three days of speeches, workshops and talk of new economy strategies for the future. One of the most decisive panels was a discussion on eliminating race as a dividing factor in the economy and social movements.

Led by Tufts University Professor Penn Loh, who is director of the Tufts Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning’s Masters of Public Policy Program and Community Practice, the panel “What Color is the New Economy” attracted a packed audience to the campus of Northeastern University, which hosted CommonBound from June 6 to June 8.

The discussion explored the hurdles to building an inclusive new economy movement with strategies for establishing cross-racial solidarity and for addressing a highly racialized economy.

“Issues around race and racism, particularly here in the U.S. with our history, are very complex and deep and we can’t escape them even if we would like to,” Loh said.

“The question we are addressing is what is the color of the new economy and why does that matter? I am hoping that we can go a little bit deeper because I think we necessarily have to talk about what is the face of the new economy.”

Included on the panel along with Loh, was the Fund for Democratic Communities’ Ed Whitfield, PolicyLink’s Chris Schildt and Brandeis University’s Jacklyn Gil.

A network of more than 100 organizations and businesses, the New Economy Coalition advocates for change to economic and political systems. The term “new economy” has come to symbolize the efforts of groups, organizations and companies to experiment with new ways of doing business, practicing democracy and sharing common resources. Some of the groups supporting the coalition include the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, Demos, Climate Justice Alliance and Shareable.

Loh asked the panelists to highlight the challenges of creating a new economy related to race and racism.

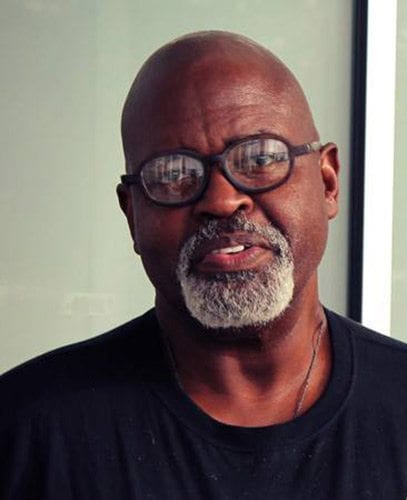

Whitfield, who is co-founder and co-managing director of the Fund for Democratic Communities and a long-time social activist involved in labor, community organizing, and peace work since the 1960s, said that he finds the concept of essentialism at the heart of the matter.

According to Whitfield, it is destructive to try to move forward and create an inclusive economy based on models that have worked in white communities as the best option for communities of color.

“We have to approach matters of race and racial healing and inclusion from a point of humility, recognizing sometimes how little we know about who is in the room or who they are or what those actual set of experiences have been, and not from this kind of essentialist position of we kind of know what is white,” Whitfield said.

He also says it is harmful not to recognize the potential agency and creativity of communities of color to determine what is the best course of action and way forward. He cautioned against what he called “well-meaning progressive folk” who are trying to do the “right thing” by trying to correct matters of race.

Schildt, who conducts research for PolicyLink on equitable economic growth strategies, including best practices for advancing equity in job creation, entrepreneurship and workforce development, said there are three things that need to be considered in developing a new economy in relation to race and racism.

The first is acknowledging that any discussion of a new economy cannot separate questions of race from questions of place and the geographic segregation of people of color, and communities of color from white communities, and oftentimes the way that opportunities are centralized in white spaces. She pointed to examples of this in housing policy, school systems and the establishment of social networks.

The second is thinking about the risk of participation in new economy models for people that have been previously excluded and ensuring security for those who step out of current modes to help develop new ones.

Lastly, she said, it is important to understand that this country has had a hegemonic white culture and white narrative that has oftentimes silenced the struggles and the victories that communities of color have had, so that any development forward must fall out of this negative pattern.

“I think one of the main challenges is really creating culturally democratic spaces that don’t just include people of color, low-income people and even those labels, but actually center and create stories and spaces that acknowledge the unique power that these communities have,” Gil said.

The panel also discussed at length the notion of new economy and if the term “new” is truly applicable considering much of what the movement draws on is already out there and existing.

Schildt acknowledged that there are difficulties with the term, “new” and said at PolicyLink they often refer to it as “equitable” economy. However, what she said is appropriate to use the term new for is that the U.S. will be a majority minority country by 2043, and many of the main cities already are, so this aspect is new. Therefore, the economy emerging out of this status would be unlike any that has come before.

“What this means for us is it poses this challenge of what will our future look like. What will 2043 look like? Is this going to be the tipping point that we acknowledge that we cannot say we are going to concentrate access to opportunity for certain groups, but leave out this growing majority? We hope that it is an opportunity to help bring along and — also particularly white people — to acknowledge that we are in this together. We cannot separate our future, our path, from the path of communities of color,” Schildt said.

Whitfield accepted the term “new” but pointed out the paradox it brings.

“We are talking about a new economic situation in which privileged and certain sections of the white community are dissipating, given the economic crisis that is so devastating to so many people,” he said.

Whitfield said he was very encouraged by what he has seen throughout the United States and the growing number of groups and organizations looking to a more inclusive future. The most promising are examining new people exercising new forms of power in new ways, new systems of ownership, and dissipating current concentrations of power.

“There are many alternatives, so I don’t even think there is one way,” he said. “I think there are many alternatives and the good thing about that is that new order, as it comes into being, if it is indeed ideologically diverse, will be more resilient than any of the single things we might figure out how to do.”