BRA seeks support for urban renewal

Push for public support comes as report finds fault with agency

For many Bostonians, the phrase urban renewal conjures up images of long-destroyed neighborhoods: the West End, the New York Streets section of the South End, Castle Square, Madison Park.

So the Boston Redevelopment Authority has its work cut out for it, embarking on a citywide campaign to gain support for the re-designation of its urban renewal districts — a process that requires approval from the Boston City Council.

Top of the list for the agency is to persuade Boston residents to get past the negative history associated with urban renewal.

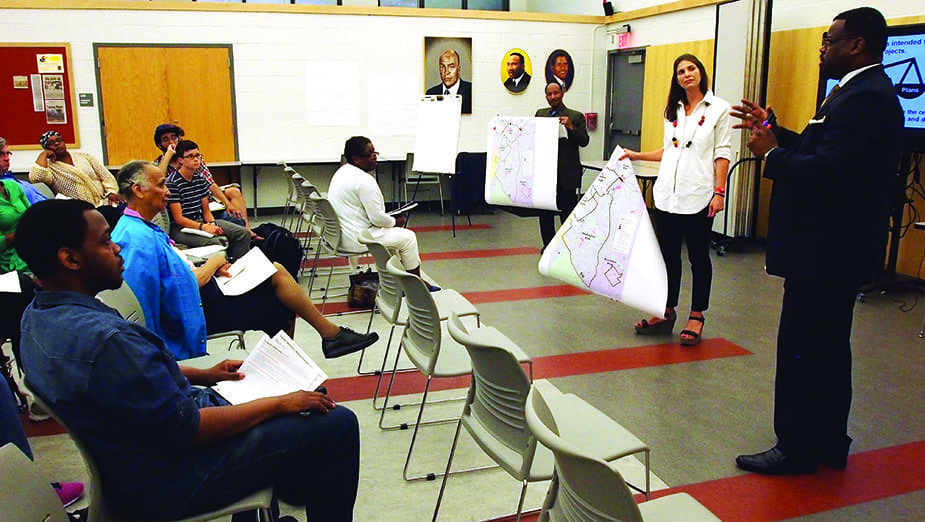

“I wish we could call it something else,” said BRA Senior Urban Designer/Architect Corey Zehngebot, speaking during a meeting with Roxbury residents. “You hear it, and immediately you have a visceral reaction.”

In some ways, Zehngebot may have engaged one of the agency’s toughest audiences in bringing the urban renewal conversation to Roxbury, where in decades past the program was referred to as “Negro removal.”

But the fact that the conversation around urban renewal is even happening underscores a shift in the BRA and how it does business. Ten years ago, when the agency sought its decennial renewal of urban renewal designations, BRA officials did so largely out of the public eye, pressing city councilors for support in secret meetings that violated state open meeting laws.

“This year, we’re approaching different neighborhoods to have a genuine process,” Zehngebot said.

On the Web

BRA urban renewal:

www.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org/planning/urban-renewal/overview

BRA operational review:

In addition to Roxbury, the BRA plans to have urban renewal meetings in the South End, Downtown and Chinatown.

This year’s push for public support comes as BRA Director Brian Golden released the results of an independent operational review of the agency, which found it lacked a cohesive vision, placed too little emphasis on planning, spread itself thin with an incongruous mix of property management, zoning and development management and failed to maintain adequate financial controls.

Golden has pledged to use the audit as a blueprint for reforming the agency. He and Mayor Martin Walsh have pledged to make the BRA more open, transparent and fair.

“We have embraced the challenge that comes with improving the way we do business, and this latest review provides the information we need to create a robust and positive plan for the future of the BRA,” Golden said in a press statement. “Change is already underway, and we are intent on delivering upon the rest of the action plan.”

Earlier this year, BRA officials announced its first major planning initiative in 50 years. The initiative, called Boston 2030, will work with residents to create development plans for each neighborhood in the city, and stitch together the individual plans into a cohesive city-wide plan. The agency will hire at least five new planners to help drive the process.

The BRA’s planning initiative comes in the midst of one of the city’s largest-ever building booms. Walsh has pledged that the city will facilitate the construction of 53,000 new units of housing by 2030 to accommodate Boston’s growing population and ease pressure on the city’s rental and real estate markets, which make Boston one of the most expensive places to rent and buy in the nation.

Under Walsh’s plan, the luxury developments going up in downtown Boston, the South End and the Fenway would be complemented by the construction of moderate- and low-income housing in the neighborhoods, drawing from the city’s supply of over 300 buildable lots.

At-large City Councilor Ayanna Pressley said the report on the BRA is an important first step for agency reform.

“I commend the mayor for doing the review,” she said. “The results confirm what we have known and experienced for some time.”

Pressley said she has been pushing for the BRA to increase its inclusionary zoning requirements, which require developers of projects with more than 10 housing units to set aside at least 15 percent as affordable units or pay into an affordable housing trust fund. She would also like to see the agency standardize its community benefits requirements for development projects, rather than requiring developers of large projects to negotiate new deals every time they build.

But Pressley said the most important fixes to the BRA will be for the agency to operate in a more transparent manner.

“Before we bring new initiatives online, we have to make sure that they’re operating in a structure that is open and transparent and accountable,” she said.

As for urban renewal, Pressley is one of 13 councilors who needs convincing.

“I have grave concerns about eminent domain,” she said. “They have their work cut out for them.”

Good intentions

Urban renewal began in the 1950s as a federally-funded program through which cities could clear sections of neighborhoods deemed blighted for redevelopment. As was the case in many cities, the BRA used urban renewal to clear neighborhoods that were working class and inhabited by blacks. While some clearances led to new developments, as was the case in Madison Park, Castle Square and in the New York Street area, which became the headquarters for the Boston Herald, many sections of Roxbury cleared through urban renewal are still vacant 50 years later.

In the early 1970s, HUD stopped funding urban renewal, moving control over the program to states. Boston is one of 31 cities and towns in Massachusetts with active urban renewal districts. Boston has 3,000 acres of land under that designation in parts of Charlestown, the Fenway, Chinatown, the South End, Roxbury, the Downtown Waterfront, the West End, North Station area, and Government Center.

At last week’s meeting, Zehngebot told Roxbury residents that urban renewal designations give the BRA tools it needs to facilitate development projects. In an urban renewal district, the agency can use the power of eminent domain to force private owners to sell land to the agency in order to assemble smaller parcels of land into a large buildable lot. The BRA used eminent domain to acquire the land and buildings in Dudley Square that are now part of the Bruce Bolling Municipal Building.

Urban renewal status also enables the BRA to clear titles for parcels of land. Because the city’s records of land ownership go back to the 17th century, it often can be difficult to establish who owns a particular piece of land. Title clearance allows the BRA to take possession of unclaimed land and turn it over to developers.

Zehngebot said the days of massive land takings are long gone.

“The BRA is no longer in the business of taking land,” she said. “We’re in the business of disposing of land to incentivize development.”

Despite Zehngebot’s assurances, Roxbury residents expressed deep misgivings about the extension of urban renewal designations.

Roxbury resident Derrick Evans pointed out that the city’s renewed investment in Roxbury comes as many long-term Roxbury residents are being priced out of the neighborhood.

“We are looking at the largest socioeconomic and racial displacement of people of color in the last 50 years,” he said. “People are moving to Brockton, Fall River and elsewhere in New England where, frankly, there isn’t this level of capital investment. Now we’re at the point on history where the alarm clock has gone off. Where all these people [downtown] say Roxbury is ripe.”

Evans echoed a refrain repeated by meeting participants last week, urging the BRA to “put people first.”

“At the core, we’re trying to create spaces for people,” Zehngebot responded. “We have to ask, ‘How does this make a neighborhood better for people.’ ”