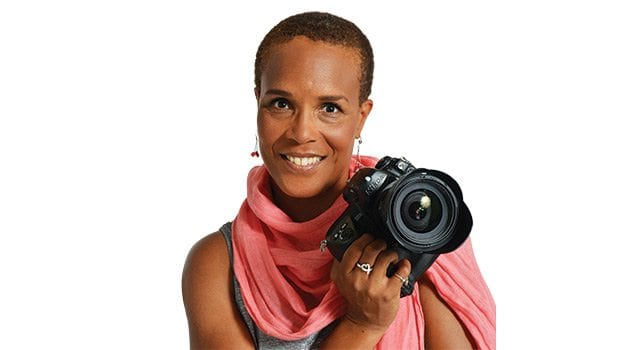

Filmmaker Tracy Heather Strain telling the untold stories

Strain has grappled with being female in a male dominated field

Tracy Heather Strain backed her way into working on films and forming her own company to produce documentaries, The Film Posse, which is based in the Fort Point Channel area.

“I was interested in film and TV as a kid, but I never thought about it as a profession,” said Strain, who grew up in Harrisburg, Pa. and came to the Boston area to attend Wellesley College. Her path to becoming president and CEO of The Film Posse Inc. wound through advertising jobs, answering the phones at a Watertown production company, and living in Harrisburg and New York City before returning to Boston in 1991 to do research for Blackside, the South End film company of the late Henry Hampton.

Strain worked her way up at Blackside, which had earlier produced the noted “Eyes on the Prize” series on the civil rights movement. She directed two segments of Blackside’s public television series, “I’ll Make Me A World: A Century of African-American Arts.” The six-part series won a Peabody Award, broadcasting’s top honor.

Then Hampton died in 1998, and Blackside unraveled without his leadership.

“People told me, ‘Oh my gosh, your first two films were so strong, people will want to work with you.’ I believed them. I hadn’t been in this position before — it seemed like I couldn’t get any work anywhere,” Strain recalled. “I was actually thinking about quitting” filmmaking.

Strain got two breaks, one after the other. She was one of the last people accepted into a Producers Academy sponsored by the Public Broadcasting Service and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. At WGBH, the Academy trained independent filmmakers and staffers at small-market public TV stations on how to create shows for national distribution.

“It kind of got me excited again,” Strain said. “Then WGBH called and asked me if I wanted to do a program on the Alaska Highway, and I said, yes. I then started my first entity, just a sole proprietorship. I worked under Diner Media at that time.”

That was 16 years ago. Strain operated Diner Media until 2005, when she renamed her business The Film Posse. It was a limited liability corporation, to protect her assets from potential lawsuits arising from accidents on out-of-town shoots. In 2008, it incorporated and merged with the production company of her husband, Randall MacLowry, an experienced filmmaker and cofounder of The Film Posse.

Challenges

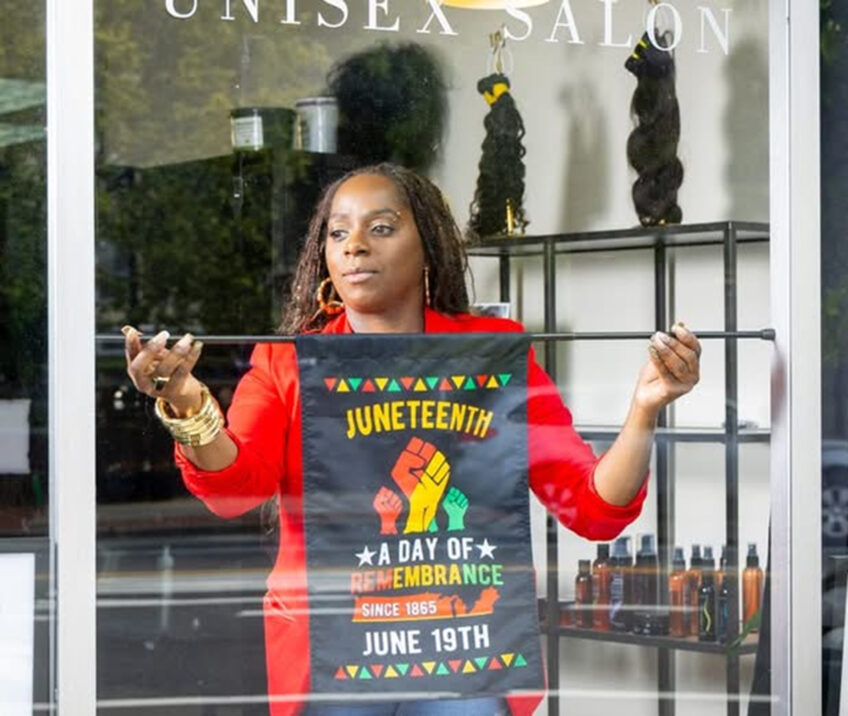

Author: Don WestTracy Heather Strain is president and CEO of Film Posse, based in the Fort Point Channel area.

Strain has grappled with challenges that come with being a black woman in a white- and male-dominated industry.

“I can’t separate the race part from the woman part sometimes,” she said. “A lot of times people think I don’t know anything, like I don’t know my stuff. There’s an assumption if there’s a technical question, I can’t answer it, especially if it’s about the computers, the Internet.”

So far, the company has produced seven documentaries commissioned for public television, most recently “The Rise and Fall of Penn Station” in New York City and “Silicon Valley: Where the Future Was Born,” both for the “American Experience” program.

How Strain has sustained her film company holds lessons for creative types, particularly the many millennials interested in working on films.

“Filmmakers think about the creative side of things, but once you establish a business entity, [you have] the same kind of concerns that a major company has,” Strain explained. “You have fewer people to take care of the details. What phone system are you going to use? What office? Can I afford this? What’s the square footage? Payroll. We didn’t have payroll at first. We just paid people by check. But [there is the need for] learning QuickBooks and double-sided accounting.”

A one-hour program commissioned for public TV comes with roughly a $500,000 budget. That has been enough, Strain said, to hire about three other people besides herself and MacLowry to make each documentary. But it hasn’t been enough to hire an administrative assistant to handle nonproduction tasks. She cited being able to afford such an assistant as one business need.

Besides commissioned films, The Film Posse has been at work on a documentary about playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry, a longtime passion of Strain’s. She also teaches film part-time at Northeastern University.

“It’s where we get our benefits from. We can’t afford to get benefits through our company,” Strain said. It has too few employees to be covered by the health insurance mandate in federal or state laws.

As with many small businesses, cash flow and diversifying revenue streams have also been challenges.

“It’s not cash flow in the middle of the commission,” Strain explained. “It’s cash flow after the commission is done, before another one.”

Strain appreciates the regular flow of film commissions from public television programs like “American Experience” and “Nova.”

“Since 2011, we’ve had steady work with films. But we don’t expect that will continue and we also don’t think it’s sound business practice,” she said. “So we’re really excited to have an opportunity to take our skills as storytellers into other kinds of work, especially short videos. I know that companies and nonprofits want their stories told.”

Representing diversity

Not all of The Film Posse’s documentaries are about racial subjects. Nor were Blackside’s, despite its name.

“What we try to do when the topic on the surface has nothing to do with race or African Americans is, we try our very best to interview someone on camera. If that’s not possible for a variety of reasons, we try to make sure in our archival (film) searches we represent diversity,” Strain said.

For years, she has been working on what would be the first full-length documentary on Hansberry, who authored the play “A Raisin in the Sun.” Hansberry was explored in one of her “I’ll Make Me a World” segments. “She’s on the shero list,” Strain said.

The film for the “American Masters” program of WNET-TV in New York is coming closer to fruition. The Film Posse has received a $500,000 grant from the National Endowment from the Humanities and raised another $100,000 in a Kickstarter campaign. The company recently received a $100,000 grant from the Ford Foundation to round out the budget for the film, titled “Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart,” from a Hansberry quote.

Strain is taking a leave from Northeastern this academic year to devote more time to the film-in-progress.

“I think it’s very important for us to tell as many stories as we can about African Americans. There’s so many stories that haven’t been told, present day stories, historical stories,” Strain said. “Sometimes it’s feels like it’s easier for people who are not African American to get the money to do those stories. But I shall persist.”