Pop artist’s works stir the spirit

“Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” comes to Cambridge

Visible from the Southeast Expressway, Boston’s iconic gas storage tank, streaked with bold colors, has been a sign of hope for decades. It makes the city seem a bit more light-hearted, a place where spirits can rise and find joy.

Author: Photo courtesy of Mary Anne KariaKent teaching with LIFE magazine

Its designer, Corita Kent, also brought joy and verve to people through her small-scale works. The power of her art to stir the spirit as well as her stature as a leading figure in Pop Art are evident in the exhilarating exhibition, “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop,” on view through January 3, 2016, at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge.

Curated by Susan Dackerman, who also edited the exhibition’s vibrant catalog, the show combines silkscreen prints by Kent from the ‘60s with works by peers. Mingling with the uplift of her early prints that cast rainbow hues on the gallery walls are later, darker works that reflect that decade’s national traumas, including assassinations and a controversial war.

Overdue for a closer look, Kent recently has been the subject of another major show. Earlier this year, Skidmore College’s Tang Teaching Museum organized the first full-scale survey of Kent’s works, which debuted at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

Harvard’s show is the first to present Kent and her work in the context of fellow pop artists. In the process, it illuminates and elevates their movement as well as the artists themselves. Pop emerges as a potent corrective to dehumanizing forces of all kinds.

Organized by theme, works by 26 artists are on view, including some with astonishing power and just plain delight. Of the show’s 150 works, more than 60 are by Kent, shown alongside those by such contemporaries as Andy Warhol (a fellow practicing Catholic), Jim Dine, Marisol Escobar, Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Bridget Riley, Faith Ringgold, Ed Ruscha, and May Stevens.

Born in Fort Dodge, Iowa, Frances Elizabeth Kent (1918-1986) became a Roman Catholic nun in 1936, joining the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and taking the name Sister Mary Corita. In 1947, she began teaching art at the Immaculate Heart of Mary College in Los Angeles and headed its art department from 1964 to 1968.

Kent introduced her students to shows of the city’s emerging Pop artists, including the 1962 debut of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans. By the mid-1960s, Kent ‘s own Pop art prints were showing at galleries across the country, and she was featured on magazine covers as the exemplar of a modern nun.

Kent took commissions, eager to reach audiences of all kinds. Her projects included an album cover for the Jazz Crusaders and a hugely popular “love” stamp for the U.S. Postal Service. Her 40-foot-long banner for the Vatican Pavilion at the 1964 -1965 New York World’s Fair updated the Beatitudes with quotes by Pope John XXIII and President John F. Kennedy. In 1965, she led her students in creating the Christmas window display in IBM’s Madison Avenue showroom, which proved controversial for its implicit protest of the Vietnam War.

But tensions grew between the sisters and the conservative local archbishop, and Sister Mary Corita left the order in 1968, moved to Boston and returned to secular life as Corita Kent (Soon after, her order separated from church jurisdiction and it is now a lay community). In Boston, Kent continued her work as an artist until 1986, when, at age 67, she succumbed to cancer.

Right away, the exhibition draws us into the verve of Kent’s world and her bold, playful, experiments as an artist and teacher.

Responding to the call of Pope John XXIII at the Second Vatican Council in 1962 and in his encyclicals, priests enlivened the Catholic liturgy, saying Mass facing the people, in their language, rather than in Latin.

Author: Artwork courtesy President and Fellows of Harvard College“The juiciest tomato of all” screenprint

Kent saw in Pop’s mass-production printmaking techniques and embrace of everyday items, from ads and packaged products to highway signs, a language that suited her ambition: to create nothing less than a new form of prayer attuned to the modern world.

At the entrance, a video shows the thousands of slides Kent took of store displays, foods, and logos, to create a stockpile of raw material. Her nimble voice is audible throughout the galleries, as videos show the charismatic Kent teaching and, with her students, transforming the college’s annual Mary’s Day feast from a staid procession into a high-spirited celebration in which students, teachers and faculty, flowers in their hair, danced, sang, and carried hand-made floats promoting peace and justice.

The first gallery offers an all-star sampling of fellow Pop artists then working in LA. including a beguiling book with hand-colored lithographs by Andy Warhol, “Wild Strawberries” (1959). Open to a charming drawing of a roast piglet, with a faux recipe penned by his mother, Julia Warhola, the book is a gentle riff on class and consumption.

Kent’s prints create a dialogue with the viewer. She takes the familiar—such as an advertising slogan—and with the medium of silkscreen printing, reverses, crinkles and twists its letters into a resulting image that triggers fresh associations. She accompanies it with small, handwritten subtext that draws the viewer’s scrutiny and, like a whispered aside, reflects on a deeper reality.

Her subtexts quote biblical passages as well as such kindred spirits as Martin Luther King, Pope John XXIII, poet E.E. Cummings, philosopher Albert Camus, and her friend Father Daniel Berrigan, a Jesuit priest and antiwar activist. She designed the covers for many of Berrigan’s books, and he wrote the preface to her 1967 book “Footnotes and Headlines: A Play-Pray Book,” which is a sort of manifesto. In the book, Kent describes her prints as “a new form of praying . . . through the words and phrases and headlines and ads and footnotes that surround us.”

In one of the prints on view, Kent juxtaposes a motto for a men’s cologne, “Tame It’s Not,” with hand-lettered passages from philosopher Soren Kierkegaard and A.A. Milne’s “The House at Pooh Corner” on fear and hope.

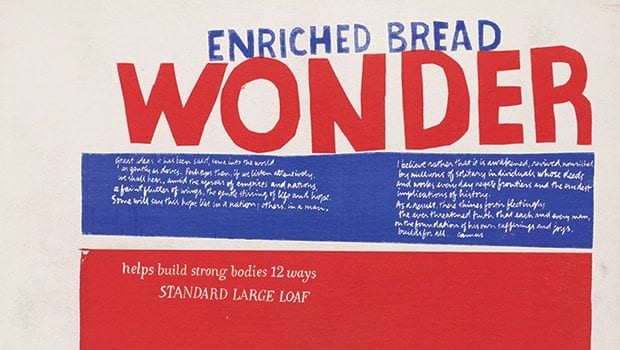

While other artists incorporate food images into their prints, Kent relies on words associated with food, such as marketing slogans and brand names.

In her prints, brands such as Wonder Bread and phrases become cues to reflecting on another kind of wonder: the communion wafer that Catholics believe turns into Christ’s body during the Eucharist.

Author: Artwork courtesy President and Fellows of Harvard CollegeA screenprint by Corita Kent titled “if i.”

Alongside Kent’s prints are works by other artists who also reinvent words as objects. A 1969 lithograph by Ed Ruscha turns a string of letters into freestanding, cupped ribbons. Ruscha, a lapsed Catholic living nearby, once told an interviewer, “I like the idea of a word becoming a picture, almost leaving its body, then coming back and being a word again.”

The college’s printmaking studio was near a Market Basket store and its prepared foods and ads became signs of spiritual nourishment in Kent’s hands. Fearless, Kent was bold and inventive in her prints. Aglow with a bright red and yellow palette, a print entitled “the juiciest tomato of them all” (1964) makes a startling comparison between Mary, the mother of Christ, and a tomato.

Kent and her Pop Art peers also found raw material in LA’s mid-century car culture and suburban sprawl. Roy Lichtenstein uses the reflective plastics of road signs to create a shimmering series of landscapes. Kent’s monumental four-part series of screenprints, entitled “Power Up” (1965), combines the Richfield Oil slogan with a long prose poem by Father Berrigan.

In the late ‘60s, Kent’s preoccupations turned to protest, including opposition to the Vietnam War and struggles for civil rights. Instead of sophisticated primary-color compositions that remix familiar words and slogans, some of Kent’s later prints incorporate searing photographs clipped from news magazines. Rendered in a muted palette, the prints combine the images, reprinted as high-contrast negatives with handwritten texts by Walt Whitman as well as contemporary pacifists. More polemic in tone, the works reflect the urgency of Kent’s purpose but seem dated in comparison with a masterpiece of the same period by Warhol.

Warhol’s still potent “Flash-November 22, 1963” (1968) recreates with stunning immediacy the fractured unfolding of news about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. A series of high-contrast, reverse negatives in varied colors shows familiar scenes — the smiling president and first lady, Lee Harvey Oswald, the rifle, the window from which the shot was fired, and a campaign poster — alongside text that mimics the terse wording of wire reports.

Among the works by Kent that retain their energy and freshness is the 150-foot-high giant seen by thousands of commuters every day. On view is the seven-inch-high wooden model Kent made in 1971 for her Boston Gas Company commission to design the exterior of the tank, and a large photograph of the finished work, which was executed by professional sign painters. Now owned by National Grid, the tank was replaced in the ‘90s and, by popular demand, Kent’s design was restored. Its rainbow motif evokes “bow in the sky” promised in the Book of Genesis as a sign of God’s bond with humankind.