“Eyes With Wings,” the title of Arni Cheatham’s photography exhibit at the Piano Craft Gallery, is a metaphor for birds and their superior visual acuity — and also reflects the artist’s approach. Out in nature with a camera, he lets his own eyes “take wing” and then works to share the joyous experience through photographs.

A long-time jazz saxophonist too, Cheatham will be honored Nov. 17 at Hibernian Hall’s “Sparks for Arts” gala with a Community Catalyst Award for his long tenure as a Roxbury-based jazz musician and music educator.

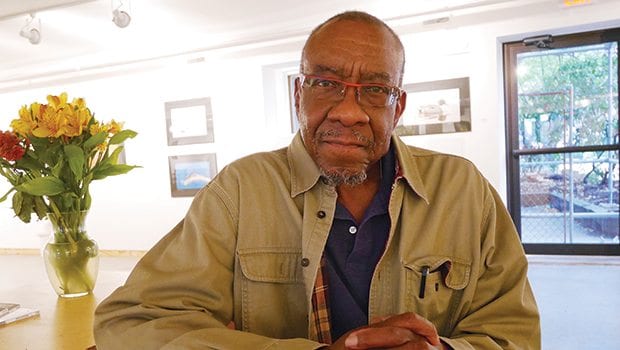

Cheatham spoke with the Banner in the gallery recently about his current exhibit and about life as an artist.

Of all the subjects out there, why do you photograph nature?

Arni Cheatham: I do have other types of images — I do a little street photography, and a little bit of abstract stuff. But when I’m in nature, I’m meditating. I place myself in nature and realize I’m just a small part of the entire world that we live in. It’s good to be in that place. There are a lot of people you run into that are very self-impressed, like, ‘I know it all.’ You get out in nature and hang for a while and realize, no, you don’t know anything!

Do you find nature within the city or do you travel for it?

AC: Well, I don’t have a large budget. The images in this show include a red-tailed hawk in Mount Auburn Cemetery … a pintail duck right behind Chestnut Hill Mall … a tulip on Newbury Street. Ninety percent of the time I go out the door, I have a camera with me. There have been longer journeys. The puffins were way up in Maine, spitting distance from the Canadian border. There are two here from Savannah, Georgia. I have a series that I haven’t printed yet from the Pacific Northwest.

Talk about your craft – how do you create these images?

AC: You have to be willing to be patient. Getting that shot [of birds on the beach] at Plum Island took maybe six minutes — but I was out there all day to get that six minutes. Patience is your tool. You have to expect that something good might happen, but even if it doesn’t, just be there.

Birds have a 30-foot fear circle. You get inside that, they get nervous. First they’ll turn their back to you. And then they’ll fly. But if you get low, you’re less threatening. If you’re very still, they’ll come up to 15 feet from you. When you lie down on the ground and ‘be the bird,’ it’s a whole different experience — you see the amount of energy it takes them to feed themselves, the running back and forth. A wave comes in, and they run, and the wave goes out, and they go running back and pick up little bits of food.

I’m often asked about camera type, which is 100 percent irrelevant. It’s not about the box, but the person behind the box. What’s more important is my tripod. No matter how stable you think you are, you’re going to [shake]. I embraced digital photography in 2003 or so. For bird photography, you have to shoot a lot of images. Birds don’t stay still. So economically, I couldn’t do the amount of bird photography I do using film.

When did you take up photography? How did you learn it?

AC: It was something my father was interested in, when I was growing up in Chicago. He bought me my first camera when I was about 12. He would let me borrow his more advanced cameras, and we’d hang out and look at proof sheets together. And I worked with him in a photo reproduction company for several years. Then I was drafted into the military. A couple of years after I got out, I moved to Boston. When I started doing educational programs here in New England, I needed something dramatic to show kids how a saxophone works, how flutes work, how flutes are made. So I bought some camera gear and made slide shows so I could show them, ‘This is a saxophone. This is a reed. This is how it works.’

All of the sudden I had this gear, and decided to see what else I could shoot. It was kind of what I call the Topsy effect – like, ‘How’d you get so big? I just growed.’ In a formal photography program, after you get past the basics, they’re teaching you to see. I taught myself how to see. I’m still in the process. And I love it.

You turned 71 recently. How are you a different photographer now than at 25 or 30?

AC: You develop a body of experience that informs what you do next. I have some older work that I may not even show any more. You refine yourself. As time goes by, I’m also taking measure of the fact that it takes more effort and energy to get out in the field than it did 10 years ago, so I have to pick my [photo shoots] more carefully.

How does it feel to put your art on display?

AC: They say the difference between a professional and an amateur photographer is the size of the professional’s wastebasket. I edit ruthlessly. From the click to the print you see on the wall, I do everything myself. I do my own framing and matting, I do my own printing, and the burning and dodging, cropping, whatever it takes to make an image really sing. When I’m soloing jazz on stage at 50 miles per hour I may make some mistakes, but here I have an opportunity to examine the output first and say, ‘This is as close to perfect as I can get it.’

What do you want viewers to take away?

AC: First and foremost, as I mentioned, being out in the field is an exercise in remaining small in the greater scheme of things. It’s not about me or my ego. I have a book of musical compositions, and inside it says, ‘The most fun is when I get to hold the horn while God plays.’ That’s where I’m coming from musically — it is a privilege to be up there and be a conduit through which something happens. And hopefully it’ll bring a moment of joy to the audience. It’s the same thing here. I want to give the audience, whether it’s a musical or visual audience, a moment of joy.