Governments must assure their citizens of protection from criminals. Massive imprisonment is the strategy in the U.S. Unfortunately, it does not work. Recidivism is so high that the convicts are soon back in jail after a short time on the street. But there is a growing belief that providing a college education to qualified prisoners might help to resolve the problem. This approach was initiated by Boston University in 1972, and a recent study at the Bard College program demonstrates that education leads to substantial reduction in recidivism.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), 2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in prisons and jails across the U.S. in 2013. That is the greatest prison population of any country in the world, and the highest per-capita rate of incarceration of any major country. Nonetheless, massive imprisonment is only a temporary solution. Prisoners serve their sentences, are then released, and they soon run afoul of the law again.

A BJS study on recidivism of prisoners released in 30 states in 2005 shows that the years in jail have not corrected the behavior of many of the 404,638 prisoners in the study; more than a third were arrested in six months after release. The percentage of those arrested increased each year until it reached 76.6 percent within five years. The study found that prisoners 24 and younger had a higher rearrest rate of 84.1 percent. The rate was 69.2 percent for those 40 and older.

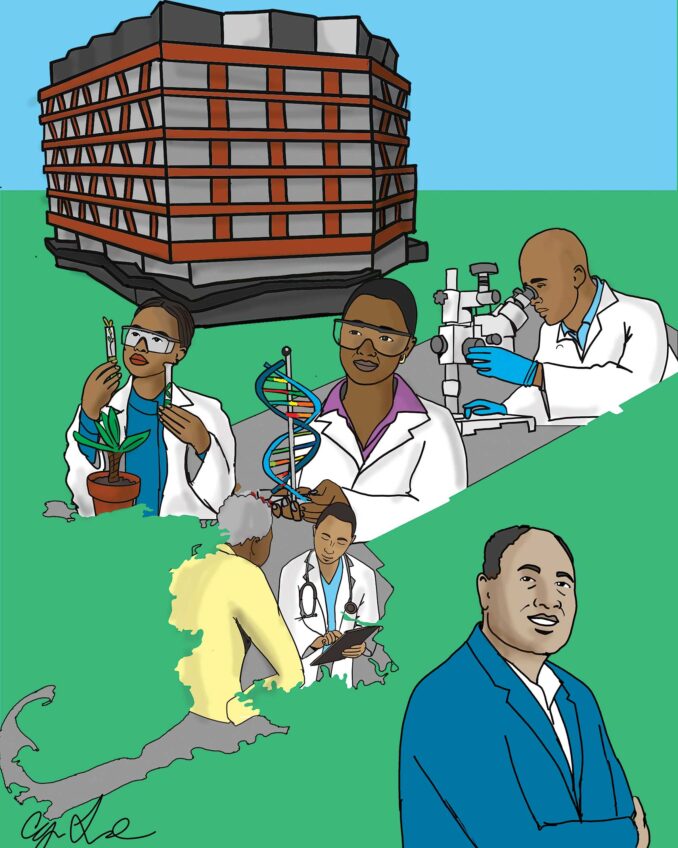

Clearly, massive incarceration provides only a temporary measure of protection to the public, and the situation will become worse as employment opportunities require greater education or training in order for those in prison to be prepared for a productive life upon release. Boston University became concerned with this problem 44 years ago when it launched a college degree program inside prison. The Prison Education Program, which began at MCI-Norfolk, has expanded and continues today.

Such programs were undermined during the 1990s when mean-spirited conservatives passed legislation to deny Pell Grants to imprisoned felons. They believed that such citizens should be punished, not rewarded with a free college education. Nonetheless, former BU President John Silber strongly supported the program and backed the late professor Elizabeth “Ma” Barker, the founder of the program, with university funds. Boston University still continues the program in its Metropolitan College.

According to a recent report in The New York Times, Bard College has found that recidivism is only 4 percent for those who merely participated in their education programs and 2.5 percent for those who actually earned a college degree. They also found that savings in public funds amount to $4 or $5 in imprisonment costs for every dollar spent on prison education.

In his effort to reform the criminal justice system, President Obama now calls for expanding Pell Grants for college education behind bars. Academic education is a good way for those incarcerated to spend their time. In addition to acquiring needed skills, the academic process induces prisoners to become more contemplative about their lives.

Even in prison, college is not for everyone. A high percentage of prison inmates lack a high school diploma, and many are only semiliterate. There also should be programs to raise the level of literacy and provide vocational skills needed for employment after inmates’ release from prison. When former prisoners have the prospect of a productive life, then all citizens will enjoy greater safety from violence and criminality