Art of Jazz

The exhibit is on display through May 8 at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African-American Art in Harvard Square

Jazz is a visual experience, particularly in its solos and small combos.

In the sensational, jam-packed show, “Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes,” on view through May 8 at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African-American Art in Harvard Square, the captivating forms of the instruments themselves are celebrated in an installation by pianist Jason Moran.

Moran arranges an acoustic bass, a drum kit and a piano on a platform while on a video he performs. In between, he converses about jazz and visual art with Vijay Iyer, like him a pianist whose music embodies both the history and future of jazz.

Curated by Harvard art historians Suzanne Preston Blier and David Bindman along with gallery director Vera Grant, the show fills the Cooper Gallery and also extends to a room in the nearby Harvard Art Museums, where a small selection of works on paper and objects are on display. But most of the show resides at the Cooper Gallery, which is open Tuesday through Saturday from 10 to 5 and offers free admission.

In the same room as Moran’s installation is a magnificent wall-size mural by Whitfield Lovell, “Servilis” (2006). On interlocked planks, he has drawn a group of African American women wearing aprons. They are seated in a solemn pose like that of a formal portrait of a wealthy European family. Five stuffed black crows stand on pedestals of varying heights in front of the mural.

Author: Photo: Courtesy Cooper Gallery“The Blind Singer” by William Henry Johnson (c 1945).

A joyous reunion

Elsewhere in the show is another evocative Lovell installation, “After the Afternoon” (2008), a stack of vintage radios accompanied by mid-’50s recordings. Lovell’s works, like the show as a whole, bring the past to life, mingling it with the present — just as a jazz musician echoes the past while creating the new.

What makes this show sensational is the joy of reunion it sparks by bringing together African American visual art and music from the early 20th century through today. Many of the visual works stir the same feelings as the music — the excitement of brass, the consolation of the blues, the joy of swing, the gravity and warmth of lyrical improvisation.

Among the objects on display are album covers by renowned artists. Aaron Douglas, a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance, created the modernist cover of “The Gold and Blue Album” (1955) for the Fisk Jubilee Singers, with its elegant, elongated figures evoking African statues. Also on view are covers with geometric designs by Bauhaus innovator Joseph Albers and Romare Bearden’s vibrant red, yellow and black design for a 1978 album by Donald Byrd, “Thank you for Funking Up My Life.”

Promotional posters for films, clubs and stars such as Lena Horne and Josephine Baker stand alongside a large expressionistic portrait in oil by Beauford Delaney entitled, “My Friend James Baldwin” (1966).

Juxtapositions of photographs, books and works on paper inspire improvisation in the viewer, triggering one’s own memories of the music and its performers. Hugh Bell’s scenes in clubs render the smoky veil of a room as well as the musicians. His portraits include a regal Billie Holiday in a Carnegie Hall dressing room and a sensuous Sarah Vaughan, in a photo that has been reproduced as a postage stamp.

Bell’s album cover photo of Sonny Stitt shows the saxophonist looking as downbeat as the album title, “Sonny’s Blues.” Nearby are books from the ’20s including a collection of poems by Langston Hughes entitled “The Weary Blues,” essays on the blues edited by composer W.C. Handy, and stylish illustrations by Aaron Douglas.

Nearby are photographs by Carl Van Vechten that show a dapper portrait of Handy, Bessie Smith queen-like and swathed in satin, a youthful Dizzy Gillespie with his trumpet, and dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson barebacked, in a portrayal of sculpted beauty.

In his collage entitled “Nights in Tunisia” (1986 est.), Walter Davis intertwines stencil-thin bits of musical scores, maps and colored papers to create a tribute to a breakthrough Dizzy Gillespie composition. “Bird Flight” (1979) swirls as if recreating the ascent of a Charlie Parker sax solo. Another striking piece by Davis is “Black Bird Totem” (1970), a composition of stacked 10-inch squares in red, yellow and black that confers an air of sanctuary.

Ming Smith conjures key figures of African American cultural life with surrealistic photographic prints. Her subjects here include singer Betty Carter and musician Alice Coltrane. She evokes Coltrane’s cosmic aspirations by portraying her as a naked figure immersed in clouds of color. Ming’s tribute to novelist Ralph Ellison, entitled “Invisible Man with Borders” (1998), shows a lone figure walking on a lamp-lit street, leaving a trail of footprints in snow.

Author: Photo: Courtesy Cooper Gallery“Miles Davis” by William Coupon (1986)

Local angle

Roxbury-raised Richard Yarde, who died in 2012, often spoke of learning to see patterns by observing his mother, a seamstress, as she worked with assorted fabrics. His sense of form works its magic in his exuberant image of two jitter-buggers, “Heel and Toe” (2006), and the fabulous “Brass Band” (1981), an aerial, abstract view of a marching band as a grid that explodes with rhythmic verve. Both translate music into motion.

The glory of brass and the glitter of gold mingle in an installation assembled by Christopher Myers entitled “Echo in the Bones.” A small blue room houses Lina Viktor’s sumptuous art deco wall panel, whirling with 24-karat gold; and a display of shiny brass instruments — fantastical hybrids with multiple horns—alongside a marching band uniform. A haunting sound track of brass music mingles a traditional Vietnamese funeral song with a New Orleans classic by Mississippi John Hurt.

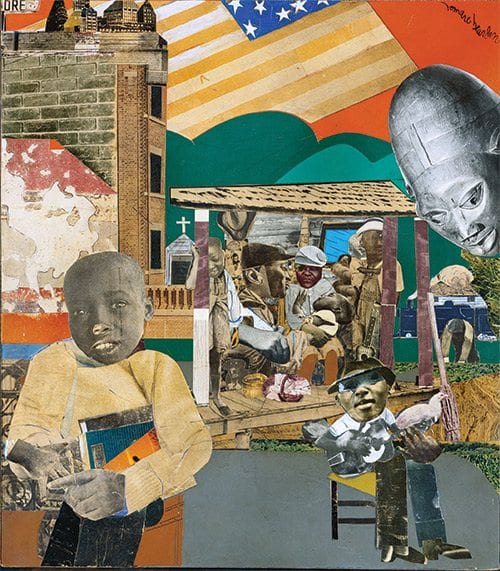

Take the short walk over to the Harvard Art Museums, open daily and free Saturdays until noon, to see the small work that captures the large spirit of this show. In his collage, “Soul History” (1969), Romare Bearden layers images that evoke centuries of African and African-American history, including an Egyptian mummy’s head, a worn American flag, a brownstone stoop, old men in overalls, a worker bent over a plantation field, a guitar player, housing projects, a church spire, a rural porch, and, his back to all that, a young boy holding schoolbooks, with his finger pointing forward.