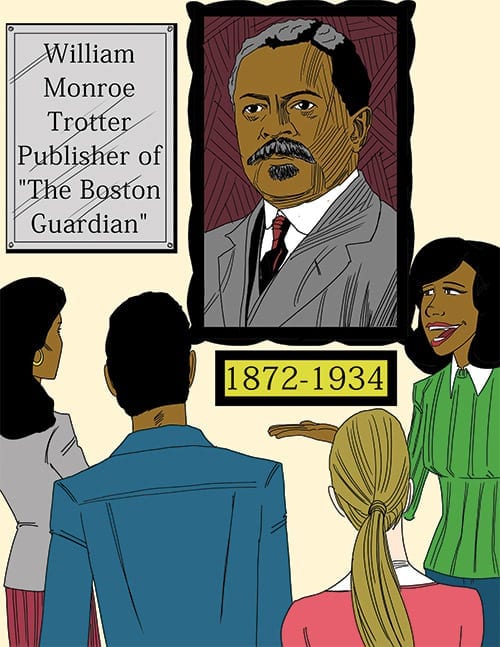

Since the beginning of the republic, Boston has been the site of opposition to injustice. In 1770, Crispus Attucks’ aggressive opposition to the occupation by British troops provoked the Boston Massacre. In 1773, Samuel Adams and Paul Revere were among the colonialists who dumped crates of tea in Boston Harbor to protest taxes. In 1854, Boston abolitionists invaded the courthouse to free Anthony Burns who faced charges as a runaway under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. And in 1916, William Monroe Trotter, publisher of the Boston Guardian, led opposition to the public showing of the racist film “Birth of a Nation.”

Recently, WGBH, Boston’s PBS station, aired a documentary entitled “Birth of a Movement: The Battle Against America’s First Blockbuster.” The film was about Trotter’s unrelenting battle for full equality for African Americans. As the first black Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard, Class of 1895, Trotter was understandably unwilling to accept the diminished role in society that was approved by Booker T. Washington. Trotter persistently publicized his point of view.

In post-slavery America, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that the division of the races was constitutional as long as it was “separate but equal.” On the basis of that Supreme Court decision, whites believed it was lawful to treat blacks as inferior and establish Jim Crow, a social pattern of racial segregation.

D.W. Griffith, the most imaginative filmmaker of the era, produced a film called “The Clansman,” about the Civil War and Reconstruction. He portrayed the KKK as the savior of society against the savage blacks. The depiction of blacks was so derogatory that the film has been described as “racial pornography.” The title of the film was changed to “Birth of a Nation” for its presentation up north where the clan might not be highly regarded.

The two central characters of the documentary are Griffith, a groundbreaking filmmaker, and Trotter, whose strategies for protest and opposition established a model for the Civil Rights Movement to come. It should come as no surprise that Boston’s black community holds Trotter in the highest regard, and the Boston Guardian newspaper has a special position of respect although it has not been published for many years. Trotter died in 1934. His sister Maude and her husband, a friend of Trotter’s from Harvard named Dr. Charles Steward, continued publication for many years. Dr. Steward, the last of the so-called Boston Radicals who were involved in the “Birth of a Nation” protest, died in 1967.

But if you live in the Back Bay or Beacon Hill you might still get a Boston Guardian every week. David Jacobs decided to appropriate that newspaper title when he found it inadvisable to continue publication of his Boston Courant under that legend. Any copyright protection of the Boston Guardian had expired, but Jacobs was nonetheless informed that the Guardian had special historical significance.

Even more disappointing was that the Anti-Defamation League failed to understand that Trotter and his newspaper are still sacrosanct to many people. The ADL is usually more sensitive to black-Jewish conflicts and the necessity of preserving the quality of that relationship. Now every week there will be another desecration of the special status of Trotter’s Boston Guardian. Certainly Trotter’s protest against racial defamation ranks up there with other early Boston oppositions to injustice.