‘Matisse in the Studio’ MFA exhibit focuses on artist’s ‘working library’ of artifacts

Like alchemists working in labs to turn everyday matter into magical elixirs, artists frequent their studios to go about their business of transformation. Take French modernist Henri Matisse (1869-1954), who wanted nothing less than to invest his works with a life of their own.

Author: “Maquette for red chasuble designed for the Chapel of the Rosary of the Dominican Nuns of Vence,” Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954) late 1950 52 Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, Museum of Modern Art“Maquette for red chasuble (front and back) designed for the Chapel of the Rosary of the Dominican Nuns of Vence.”

On the web

For more information, visit: www.mfa.org/exhibitions/matisse-in-the-studio

One of the great painter-sculptors of the twentieth century, Matisse was not content to reproduce what the eye can see. Instead he worked to render the essence of his subjects.

“Matisse in the Studio,” the fascinating exhibition on view through July 9 at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, explores the artist through his life-long relationship with a collection of objects — mainly African, Islamic and Asian artifacts. He bought them in flea markets and curio shops and from antique dealers who trafficked in booty from Europe’s colonies in the Middle East, Asia and North, Central and West Africa. He also purchased such objects on his travels to Algeria and Morocco, and in Spain, where he explored the country’s Islamic architecture.

These objects formed what Matisse described as “a working library,” a portable studio that fed his imagination and growth as an artist. His collection moved with him to his successive homes, first in Paris; then in Nice, on the French Riviera; and from 1943 to 1948, in the mountain town of Vence, where he waited out the war before returning to Nice.

The exhibition presents 40 of these objects alongside 70 works by Matisse from all stages of his career, including paintings, sculptures, cutouts and drawings. Many are on public view for the first time outside of France.

The MFA is the only U.S. venue for the show, which will travel to the Royal Academy of Arts in London from August 5 to November 12. Organized by the MFA and the Royal Academy in partnership with the Musée Matisse in Nice, the exhibition is accompanied by a lustrous catalog with essays by renowned Matisse scholars, including the show’s curators: Helen Burnham, of the MFA; Ellen McBreen of Wheaton College; and Ann Dumas of the Royal Academy.

Author: “Interior with Egyptian Curtain,” Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954) 1948 Oil on canvas The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., © 2017 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.“Interior with Egyptian Curtain.”

The object

Beguiling from the start, the show begins in the first gallery with a prelude. On view is an Andalusian glass vase Matisse bought in Spain in 1910. Surrounding it are two paintings in which the vase plays a starring role. In one, “Vase of Flowers” (1924), the light shimmers through the vase. In the other, painted a year later, its surface is rendered in opaque patches of paint.

Nearby is a wall-size reproduction of a photograph showing about 20 of Matisse’s objects, including the vase, arranged in rows like a family portrait. Sending the photograph to a friend in 1946, Matisse wrote on the back, “Objects which have been of use to me all my life.”

The first of the exhibition’s five sections, entitled “The Object is an Actor,” shows how Matisse regarded his objects as a cast, with roles that change within each composition. “A good actor can have a part in ten different plays,” he said in 1951, “and an object can play a role in then different pictures.” A pewter jug stands out in the alluring “Vase of Anemones” (1918), its shimmering, spoon-like shape echoed in a small vase by its side. In another painting, it appears in silhouette, on a wall.

The sections entitled “The Nude” and “The Face” follow Matisse as he adopts the language of curves and counter-curves he discovers in African sculptures and masks, and their power to convey character rather than simply rendering a likeness. Matisse’s painting of his 13-year-old daughter renders her face as a composition of simple contoured lines, echoing the curves of an African mask. Pablo Picasso purchased the portrait and displayed it his studio next to a mask from Gabon.

From 1910 to 1913, Matisse portrayed a woman named Jeannette in a series of five bronze busts, each more abstract than the one before. The first of three on view is a naturalistic rendering. By the third, her facial features and hair have dissolved into a spare, elongated mass of curves and planes.

Islamic influence

The fourth section, “Studio as Theatre,” evokes the Islamic interiors that captivated Matisse during his travels in Spain, Algeria and Morocco. Pale grey walls provide a serene backdrop for the artist’s richly patterned Islamic tent curtains, screens, furnishings and rugs as well as paintings by Matisse that seem to grow out of the setting.

Floor-to-ceiling arched windows covered by transparent screens enable visitors to peer into adjacent galleries and reconnect with works they have already seen while encountering others for the first time. This imaginative staging invites viewers to be like Matisse and bring disparate visual elements together into an even livelier whole.

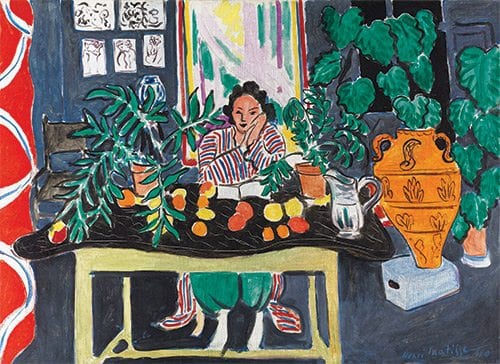

Echoing the interlocking patterns of Islamic tiles and weavings, in which no single element is the focal point, paintings such as “Interior with Egyptian Curtain” (1946) mingle views of nature and manmade objects into a harmonic whole. Rendering models within multilayered Islamic-style interiors, Matisse gives equal weight to human figures and the objects surrounding them.

The aptly titled concluding section, “Essential Forms,” displays works that culminate Matisse’s career-long quest to render “the character of the thing.”

Objects on view include Matisse’s prized artifacts from the Congo, a mask laden with shells and pearls and prestige cloths of woven raffia in beige and black geometric patterns. Commenting on these weavings, Matisse wrote to his daughter, “I never tire of looking at them…waiting for something to come to me from the mystery of their instinctive geometry.”

As he aged, Matisse worked from his bed near a mural of Chinese calligraphy that his wife Amélie gave him on his 60th birthday. Here, it is mounted close to the artist’s spare 1952 drawing of an acrobat. Seen together, the lines of both dance with kinetic energy.

Matisse spoke of the acrobat’s “ease and apparent facility” as well as “the long preparatory work that has allowed him to reach this result.” The same can be said of the expressiveness and economy he achieved as a sculptor and painter. Brimming with life and energy, the works in this section demonstrate the rewards of his long quest to invest line, form, texture and color with the distilled essence of his subjects.

Not a strict minimalist, Matisse relished an ornate baroque chair he found in Venice, and in a series of works on paper celebrates its exuberant arabesque curves.

Chapel design

Perhaps this show’s ultimate expression of his power, culminating a life exploring the harmonies of color, materials and form, is one of his final masterpieces, completed three years before his death: the Chapel of the Rosary of the Dominican Nuns of Vence. Envisioning its design, Matisse said, “We will have a chapel where there will be hope for everyone. Whatever his faults are, he will be able to leave them behind at the doorway, as the Muslims leave their shoes, dusty from the streets, at the thresholds of mosques.”

A total work of art, Matisse’s design encompassed the chapel from its architecture to its stained glass windows, interior décor and priestly vestments. On view here is a pair of paintings that replicate in full size the front and back of a chasuble, the outer cape-like garment worn by the priest during Mass. A work of supreme simplicity and elegance, it is executed in two colors, red and yellow. On the front, a streamlined cross is surrounded by smaller crosses and dashes standing for palms. On its back, an abstract image of a tree evokes the cross as the tree of life. At the center of the garment, where it overlaps the priest’s spine, lies this symbol that is the spine of Christian faith. Surrounding dashes represent still more trees, and an ever-expanding community of faith.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)