The Alvin Ailey Dance Company turns 60 next year and its five shows last week, presented by the Celebrity Series of Boston, gave ample proof that its legacy is alive and well.

At its Friday night show at the Boch Center Wang Theatre, the company demonstrated the roof-raising power of its living tradition. With a four-part program, including one Boston premiere, the company put its emotional expressiveness and physical virtuosity on full display.

The evening began with “The Winter in Lisbon,” a tribute to legendary jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Choreographed by Billy Wilson in 1992 and restaged by Masazumi Chaya with warm lighting by Chenault Spence and spicy costumes by Barbara Forbes, the work also honored Wilson, whose Broadway projects included the 1976 hit “Bubbling Brown Sugar.” For two decades, Wilson taught at Harvard and Brandeis and in the 1980s he headed his own company, Dance Theater of Boston.

Mood swings

The music for the first three segments of “The Winter in Lisbon” is from Gillespie’s soundtrack for a 1990 movie by the same name. For its sensational finale, Wilson selected “Manteca” (1947) the revolutionary mambo-bebop concoction forged by Gillespie and Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo that imported the five-stroke clave rhythm of Latin music and pioneered Afro-Cuban jazz.

The soaring “Opening Theme” drew the entire company on stage in slinky, languorous ensemble formations. Shifting to a pulsing party mood, next came “San Sebastian,” starting with a sensational solo by Daniel Harder. Bodacious in a tropical shirt, he leapt and whirled, his hat in his hand or on his head, embodying the trickster spirit of Dizzy’s trumpet passage. Harder’s solo expanded into a trio as he gained two equally athletic and exuberant partners—Glenn Allen Sims in a purple vest and Vernard J. Gilmore in striped pants. Each dancer displayed the quicksilver changes of the instruments—Sims, the rippling piano chords, and Gilmore, the drumbeats. Forming abstract shapes with their bodies, they echoed the interplay of the musicians. Then came the ladies, Rachael McLaren and Belen Pereyra, injecting their own chemistry in whirling citrus dresses.

Another shift in mood came with “Lisbon,” a slow blues piece danced with erotic flare by Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims, husband and wife. His baldness and her thick mane added to their visual oomph as they conducted a tender, suave push and pull of courtship with balletic grace. Combining sensuous intensity with light humor, their dialogue had theatrical touches they repeated like punctuation marks. She would snatch his hat in a come-hither move and he would stroke her leg. As their interlude ended, she disappeared into the darkness. His back to the audience, he stared after her, momentarily bereft, and then extended his arms upward in an exultant expression of thanksgiving.

The entire company returned for “Manteca,” filling the stage with the hot hues of their costumes and mambo-flavored dancing for a euphoric finale.

An ensemble of six men and six women then performed the Boston premiere of “Untitled America,” a 2016 work by much-honored dancer and choreographer Kyle Abraham. Rendering in dance the experience of incarceration, which disproportionately affects urban black males, the work is raw and unfinished, like its subject.

Leaden tones dominate its staging, from the grey costumes by Karen Yount to the lighting and sets by Dan Scully, which include a screen evoking a barrier between inmates and the outside world. Its soundtrack begins with a tense, throbbing percussive passage and includes occasional voices, only partially audible, a spiritual and a prison holler.

Investing their portrayal of imprisonment with dignity and flickers of emotional life beyond apathy or rage, the dancers at first mimic gestures of being arrested and handcuffed and marching in enforced formations and later, the tension between confinement and the urge to break out in spirit as well as body.

Angles and curves

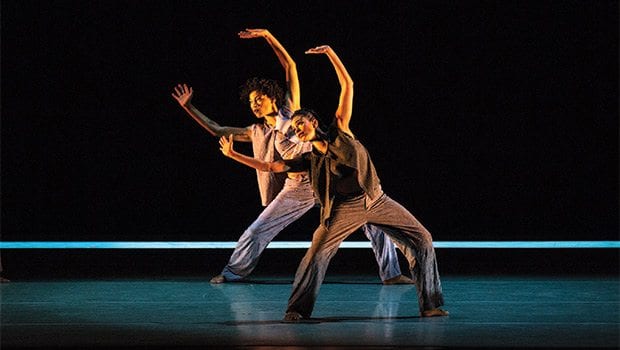

Next came the exquisite “After the Rain Pas de Deux,” choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon in 2005 for the New York City Ballet and restaged by Jason Fowler in 2014 for the Ailey company. Jacqueline Green and Yannick Lebrun performed the duet, which was as spare as its musical accompaniment, a contemplative passage by Arvo Pärt. They alternately intertwined and unfolded, moving alongside one another at a slant in parallel angles and curves. Several times, Green executed a deep and slow backbend, pouring herself to the floor. The work culminated as she brought her u-shaped body to rest and Lebrun slipped beneath her, pressing her torso to meet his, in a gesture of commitment.

The company concluded the show with “Revelations,” the signature work that Alvin Ailey created in 1960 for his then two-year-old company. The dancers performed its jubilant ensemble scenes and challenging, intense solos, duos and trios and solos with the freshness and verve of a premiere and closed with an extended, audience-clapping encore of “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham.”

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-713x848.jpg)