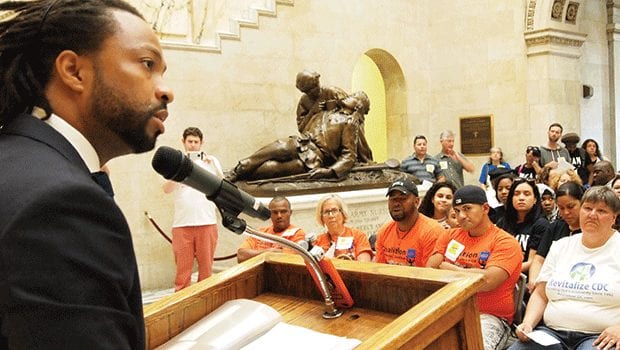

Activists call for repeal of mandatory minimums

Bills debated in State House hearing would reform sentencing

The end could be nigh for mandatory minimum sentencing on drug offenses, Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz told activists on Monday.

“This is my ninth year in the legislature and we’ve never been this close,” Chang-Diaz said to the crowd, who had gathered in advance of a hearing on criminal justice reform legislation.

Sen. Mary Keefe (left) and Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz (center) are co-sponsors of the Justice Reinvestment Act, an omnibus bill of criminal justice reforms that includes repeal of long mandatory minimum drug sentences.

On the docket: two bills that could repeal mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. One is an omnibus bill incorporating other reforms sponsored by Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz and Rep. Mary Keefe, the other sponsored by Reps. Evandro Carvalho and other officials.

The pre-hearing rally and hearing featured testimony from repeal advocates who said drug-related mandatory minimums are ineffective, disproportionately impact people of color and endow prosecutors with a power better left to judges.

While black and brown residents constitute 20 percent of the state population, in contrast they represent 40 percent of people incarcerated on drug offenses and 75 percent of offenders serving mandatory minimums, Carvalho said.

“I believe it’s a racist policy — and I used to be a prosecutor,” he said.

This creates ripple effects, Carvalho noted. People locked up are removed from the workforce and education opportunities, and once released, their criminal records may bar them from job opportunities, thus exacerbating the racial wealth gap.

A Springfield resident who was incarcerated on a narcotics offense told those at the rally that he lost years during which he said he could have been advancing in a career and contributing to society.

“During those five years [I was locked up], I was not able to get a job,” he said. “The judge’s hands were tied because of the circumstances of the case. That was my first-time offense and he wasn’t able to give me a lesser sentence. I ended up doing five years and coming home with nothing.”

Ultimately he went on to attain bachelor’s and master’s degrees and become a licensed social worker and drug counselor.

“Had I been able to get out earlier, I could’ve helped more people in my community,” he said.

A stark worldview divide emerged between former prosecutors, elected officials and civil rights workers who oppose mandatory minimums as over-used and ineffective, and district attorneys who say they are a critical tool.

Suffolk County District Attorney Dan Conley argued for keeping mandatory minimums, saying they are used only sparingly and to lock up the worst drug traffickers who drive violent crime. Meanwhile, Rahsaan Hall, director of the racial justice program of the ACLU of Massachusetts, said that often there is no distinction between a dealer and a user and that many impacted by mandatory sentencing are addicts who sell drugs to support their habit. Hall said the evidence shows it is far from “the worst of the worst” who are being trapped by such sentences: One-third of those currently doing time in Massachusetts on mandatory minimums have either minor criminal records or none at all, and more than half have moderate records or below.

While Conley said mandatory minimums are a valuable aid he credits with protecting communities, Sen. Creem said that mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses have not been shown to improve public safety outcomes or costs.

“There’s no evidence that it deters or reduces the rate of drug crimes or addiction,” Creem said. “[Or] that it doesn’t result in disproportionately long sentences.”

The debate also brings up questions on how much discretionary authority prosecutors should have to determine sentences, or if that should reside solely with judges. Conley said that he believes prosecutors are better able to assess individual circumstances than are judges.

“Judges don’t have as deep or full understanding of communities as prosecutors do as to who is driving violence.”

Meanwhile, Hall argued that even for the worst offenders, mandatory minimums are a less effective solution than leaving judges the discretion to determine appropriate sentences.

Rep. Jay Livingston said that mandatory minimums are unnecessary to secure public safety against threats.

“The worst of the worst, under any sentencing scheme, will go to jail for a long time,” he said.