Building a local economy

Ujima Project aims to put economic control in neighborhood hands

The Boston Ujima Project took a step forward last weekend with an inaugural assembly to launch its effort to build a new community-controlled economy in Boston’s neighborhoods of color.

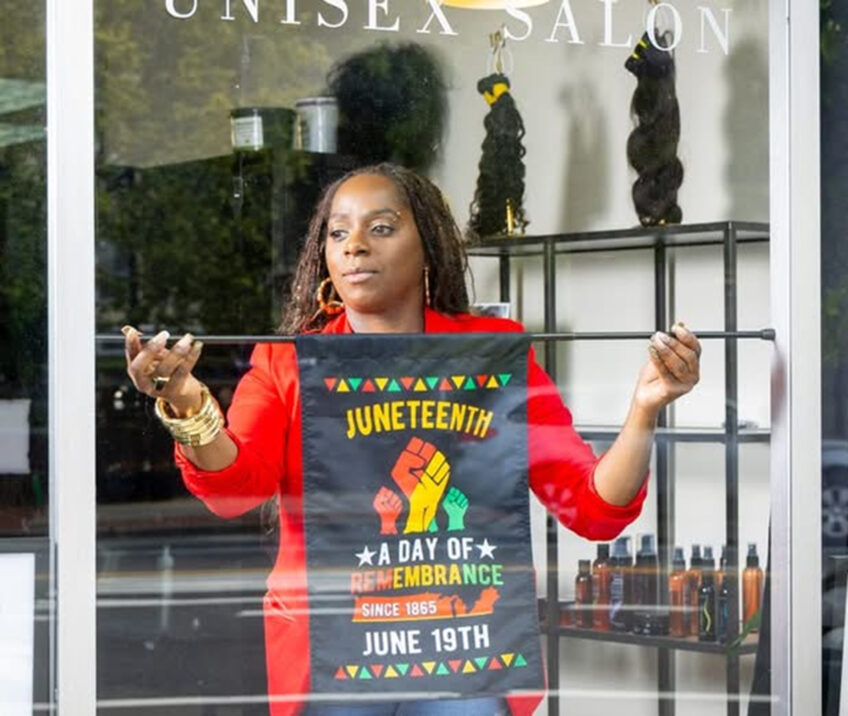

Author: Sandra LarsonEd Whitfield, co-managing director of the Fund for Democratic Communities, delivers a keynote speech at the Boston Ujima Project’s “Dreaming Wild” launch event.

On the Web

Boston Ujima Project: www.ujimaboston.com

Fund for Democratic Communities: https://f4dc.org

Called “Dreaming Wild,” the two-day event opened with a Friday evening reception and speaker program at the Bruce C. Bolling Building, followed by arts, social and networking events at nearby cafés, and continued with a daylong general assembly Saturday at the First Church of Roxbury, where founding members voted on the Ujima Project governance and board structure.

Nia Evans, Ujima Project’s executive director, said the opening event’s title is a riff on the phrase “I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams,” which has come into use in various justice movements.

“We think about the Ujima Project as a concrete manifestation of possibility,” she told the audience during Friday’s speaking program.

Ujima is a Swahili word and the Kwanzaa principle of “collective work and responsibility.” True to that, the project is a joining of many entities to build and sustain local wealth in Boston communities. A major piece will be its community capital fund, into which community stakeholders of many types will pool money. The Ujima Project’s members, through a democratic one-person-one-vote process, will share the task of allocating the accumulated funds to support local businesses, artists and organizations.

Launching formally now, the Ujima Project last year conducted a pilot project to test the process of raising and allocating community capital. At an August 2016 “Solidarity Summit,” $10,000 was raised from 175 small lenders and investors and doubled with matching funds from larger funders. The $20,000 was then allocated through a participant vote to five local black-owned and immigrant-owned businesses, each of which received zero-interest loans of $3,000 to $5,000.

The businesses selected for loan support at the pilot summit were Bowdoin Bike School, Fidalgo Wholesale, Fresh Food Generation, Sydney Janey Design and Norma’s Catering — locally-owned enterprises that were judged to be both good business prospects and contributors to the well-being of their communities.

The Ujima Project now is setting its sights higher. Starting this fall, the goal is to raise $2.5 million to $5 million over the next two years, and starting to allocate funds in early 2018. In future rounds, the capital fund goal could rise to $20 million. The loans will not typically be interest-free in the future, but rates will be capped.

Individual membership is open to all, though only Boston residents will have voting rights. The standard membership fee is $25, with discounts for various groups, such as youth age 14–24. Investment beyond the membership fee is encouraged, but not required.

The Ujima Project emerged from a year-long cross-sector study group hosted by the Center for Economic Democracy, Boston Impact Initiative and City Life/Vida Urbana, seeking more sustainable ways to fund grassroots organizations. After examining the feasibility of starting a public bank and looking at existing community-focused models such as participatory budgeting initiatives, cooperatively-run businesses and land trusts, the group concluded that while each of these models was good, none by itself was enough.

“We thought we needed to knit these models together,” Evans explained, “so the individual models can be stronger, and the system is more than the sum of its parts.”

Besides the community capital fund, part of the Ujima Project plan is to recognize and certify local businesses if they fit the community standards that members of Ujima will decide on together. The standards will consider business practices such as living wages, inclusive hiring, CORI-friendly hiring, environmental impact and affordability. These Ujima-certified “Good Businesses” will be eligible to join Ujima’s Business Alliance to gain access to capital, technical assistance and support from the community.

The Ujima Project will support the recognized Good Businesses with an alternative electronic “currency” that offers discounts to encourage customers to buy from them.

A new economy?

In addition, a skills- and time-share bank will allow individuals to trade skills and labor with neighbors on an hour-to-hour exchange. A worker services network will help employees of small businesses gain access to essential benefits, from group health insurance to workplace mediation services.

The “Dreaming Wild” opening program included a talk by Ed Whitfield, co-managing director of the Fund for Democratic Communities in Greensboro, North Carolina. The longtime activist for justice, anti-war and community causes put the importance of community control of capital in strong terms as an issue of freedom.

“We have an economy that’s not granting us human agency and happiness,” he said. “A handful of people can legally own and control the very things people need to stay alive. And we’re basically told there’s no alternative.”

But Whitfield believes there are alternatives.

“Freedom is possible,” he said. “It is possible that people can be in control of the products of their own labor.” He sees promise in “these new, creative, innovative, democratic ways to create that access within the community, so that people who have ideas on meeting needs and elevating the quality of life are able to utilize that wealth for those purposes.”