Boston prioritizes affordable housing

Some Roxbury residents call for moratorium on publicly owned land

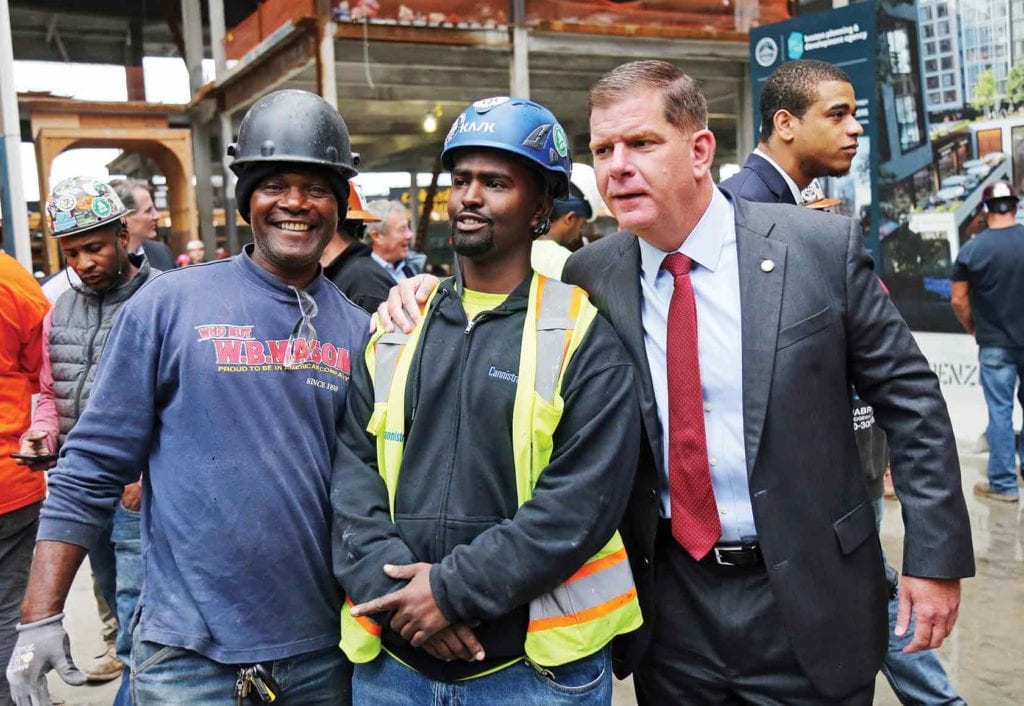

Mayor Martin Walsh’s office has made significant strides in boosting Boston’s income-restricted housing stock, but for residents and activists in parts of the city this progress is insufficient in scale, depth and pace. In Roxbury, some residents have called for a moratorium on the disposition of all publicly owned land, citing fears that new development would accelerate the displacement of existing residents.

Last week, the city’s chief of housing and director of its Department of Neighborhood Development, Sheila Dillon, met with the Banner to detail the city’s efforts to build and preserve affordable housing. She noted that the city has spent almost $125 million on the construction of 2,142 new income-restricted units since Walsh first took office in 2014.

“There’s been this very large effort to look at every asset we have to create new affordable housing,” said Dillon. “I think we’re doing a good job here at the DND and we’re really listening and ending up with increased affordable housing, oftentimes for a range of incomes.”

To this end, the DND currently manages an active pipeline of more than 7,500 affordable housing units, a slim majority of which (3,798) are for households earning between 60 and 80 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI).

“There is a feeling that the city needs to do more, but I think it’s good to reflect on what we have done,” said Dillon.

A recent report released by the DND confirmed that 19.4 percent of city’s 282,986 housing units are deed restricted, just shy of the city’s 20 percent target.

Besides building new units, Dillon’s plan involves preserving affordable housing that already exists. “We have to continue to create, but we also have to make sure we preserve what we have,” she told the Banner.

This means encouraging the redevelopment of up to 4,500 Boston Housing Authority public housing units, as well as protecting tenants in units with expiring affordability restrictions, permitted decades ago under the state’s 13A affordable housing program.

Ending displacement

In tackling displacement, Dillon highlighted the work of the Office of Housing Stability, focused on lowering eviction rates and acquiring 1,000 market-rate rental units to transform into income-restricted housing.

“We’re doing a lot of work between tenants and landlords,” she said, “we’re exposing the [eviction] issue and I think that’s really starting to take hold, showing who’s doing the evicting, where it’s happening.”

DND officials now request that developers submit an eviction prevention plan with their funding proposals. A year-on-year, 18 percent reduction in eviction rates would suggest their efforts are paying off.

Homeownership is also central to the mayor’s Housing Boston 2030 plan, revised in September with an increased target for the construction of mixed-income units, from 53,000 to 69,000, including an additional 15,820 income-restricted units.

Dillon said her office was looking into the development of better mortgage products, more flexible down payment options and ways to address credit issues that prevent many potential first-time buyers from entering the market.

“We’ve heard about [homeownership] from all neighborhoods, but especially from Roxbury,” said Dillon, a neighborhood where, according to the DND’s latest tally, 48 percent of units are income-restricted.

“People want moderate-income families and families of color to be able to buy,” she said. “We really need to find ways that people can buy in Roxbury, that they can stay and can get housing security through home ownership.”

Despite Dillon’s list of achievements and progressive proposals, some Roxbury residents and activists like Armani White criticize the DND for not building enough affordable housing for the lowest income tenants.

“There are things that the city is doing right,” said White, “but I think more needs to be done for low-income housing.”

White believes that there needs to be more “truly affordable housing that the average Roxbury resident can afford,” for those earning less than 30 percent AMI.

Building more low-income homes means “asking developers to be less greedy and to think about our land not just as an economic investment,” he told the Banner.

On displacement, White said it is not clear what, if anything, the city is doing to help stem the tide of what he considers an epidemic. Instead, he sees the DND and planning agencies engaging in “a rush to get rid of public land in this hot market,” leading to the detrimental dismissal of community concerns. “When you let planning agencies do their thing, then communities are erased,” he said.

“If you have neighbors that want to stay in a neighborhood and feel like they’re being priced out, then we don’t have enough affordable housing,” Dillon conceded.

“We need to create housing for very low incomes, but in this instance,” she said, referring to the ongoing planning process for several large parcels of land in the Dudley Square area, “we did really listen to the community and the community really wanted a mix of incomes.”

She added, “We need to go out and roll up our sleeves and have these individual conversations. I think we did that in Dudley.”

Some residents, including Project Review Committee Co-chair and Highland Park local Rodney Singleton, may agree with Dillon that a range of affordable housing needs to be built, not just for those at the very bottom of the income scale.

“We should not stop building at the low end,” said Singleton. “But too often what happens is that the middle only gets about 8 to 10 percent of the money,” meaning city, state and federal subsidies. “The lion’s share of the money goes to the lower end … and the middle always seems to get left out.”

Singleton said that there is a “sweet spot” for households earning between $25,000 and $35,000 a year, but that “what has happened is that the city has been really sensitive to make sure they don’t displace communities and have made everything affordable.” He said that by focusing on this lower end of the income scale, the housing needs of tenants in this middle bracket are underserved by the city.

“I think we should let developers be more creative, and the city has got to be willing to take some chances,” said Singleton — chances that include hiring less-well-established developers with perhaps unconventional but still feasible financing and planning ideas that meet city budgets.

Failing that, Singleton said, “We have to find subsidies” in order to build more affordable units. This may be tough, following billions of dollars of cuts to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development budget by the Trump administration earlier this year.

Citing an active market in Roxbury, Dillon noted that much of what happens on privately-owned land is not under her purview.

“Our job is to create affordable housing — to make money available and to make city-owned land available to make good, high-quality affordable housing,” said Dillon.