“Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular,” showing at the Museum of Fine Arts through June 16, doesn’t display rows and rows of Kahlo’s famous self-portraits. It does one better. Curator Layla Bermeo provides context to Kahlo’s work and separates her mythic reputation from the reality of her practice. The result is an informative look into the world around Kahlo and how it influenced her work and her carefully prepared self-image.

Often, Kahlo is seen as a lone visionary, a struggling Mexican woman who rose above her life’s hardships to change the artistic world. And certainly, there’s no questioning Kahlo’s talent and impact.

But the reality is, she was a well-educated, upper-class Mexican woman creating work alongside other artists in the context of Arte Popular. She collected artwork, she was friends with other female artists working similar genres and she wore indigenous clothing out of fashion and solidarity rather than cultural impetus. “She was as artistic with her textiles as she was with her paints,” says Bermeo.

Tehuana dress (top and skirt), 1930s-1940s. Made in Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Gift of Michael Phillips

PHOTO: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Bermeo thought it important to include 20th-century women artists who were not Frida Kahlo, and works by artists like Maria Izquierdo are shown with photographs of the artists next to them. “These are here to make the point that Frida Kahlo was not the only woman dressing this way,” the curator says. They also serve to illustrate that Kahlo had a support network. She wasn’t working alone in her room always, but collaborating with other artists.

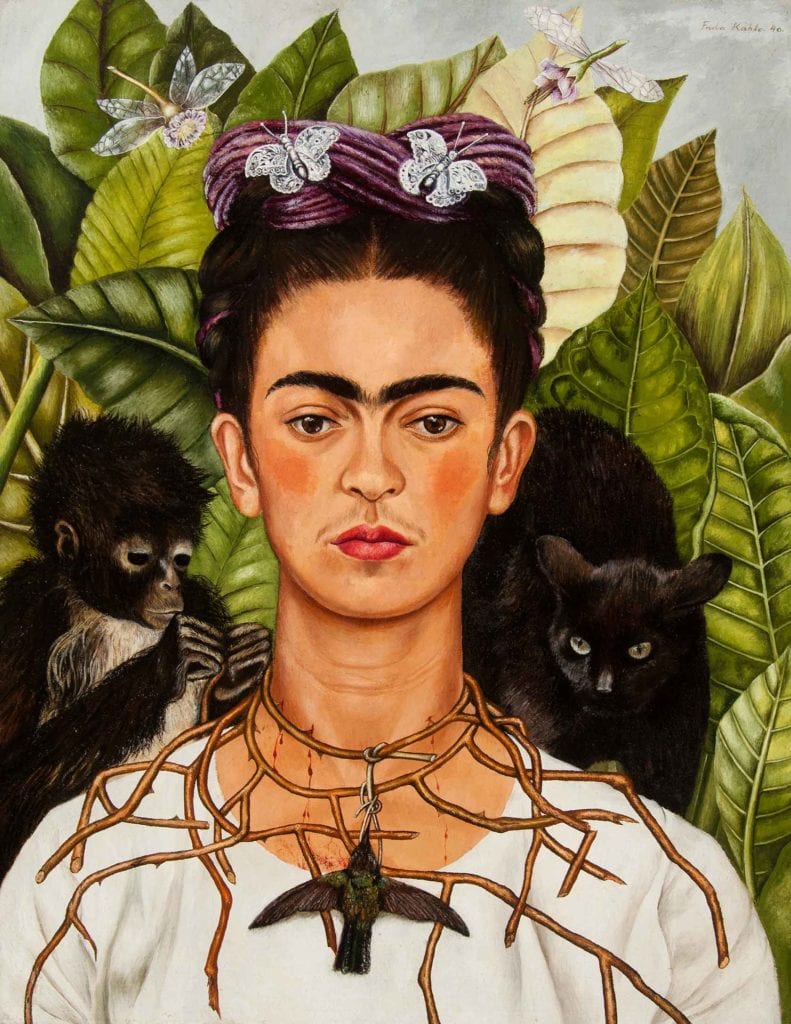

Though Kahlo’s personal objects can’t travel out of Mexico, Bermeo included a number of pieces similar to the work Kahlo collected, from small figurines and sculptures to pottery. Kahlo loved retables — decorative panels often displayed behind altars. There were an estimated 400 retables across her and husband Diego Rivera’s collections. Some of Kahlo’s retable interpretations, and works inspired by the style, are exhibition in the show. The two Kahlo self-portraits showcased are the MFA’s own “Dos Mujeres” and “Self Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace.”

Trunk, late 19th century. Made in Olinalá, Guerrero. Lacquered and painted wood. San Antonio Museum of Art, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Mexican Folk Art Collection PHOTO: Peggy Tenison. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Kahlo’s world is illustrated in this exhibition through a variety of media, including paintings, photographs and clothing. It’s designed not to discredit Kahlo but to celebrate her within her time and space. Adjacent to the exhibition is Graciela Iturbide’s “El Baño de Frida,” an eerie, powerful photographic tour of Kahlo’s bathroom, which remained untouched for decades after her death.

The ability to pull Kahlo from her heavenly status as artistic deity into a historical context only serves to make her work more accessible and more impressive.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)