People respond to trauma in different ways. In the wake of World War I, Germany, devastated by its losses and harsh peace terms, became fertile ground for Hitler. But during the same period, a group of artists in Germany launched an idealistic movement rooted in deeper and older sources than the ruins of war.

From 1919 until 1933, the group ran an influential school of architecture, art and design they entitled Bauhaus (“building house”). They were inspired by the medieval and Renaissance collaborative traditions that had created their country’s cathedrals, in endeavors that united fine artists, artisans and craftspeople to create works that benefited all and combined utility with beauty.

After closing the school under pressure from an increasingly hostile Nazi regime, many Bauhaus faculty migrated to America, where they found a welcoming community at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, a vibrant hub of innovation in design, dance, music, visual arts and architecture. After the college closed in 1957, many took faculty positions at Yale, MIT and Harvard.

Now celebrating the Bauhaus founding’s centennial, the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge is presenting “The Bauhaus at Harvard.” On view through July 28 and organized by the museum’s research curator, Laura Muir, the exhibition presents nearly 200 works by 74 artists, drawn almost entirely from Harvard’s Bauhaus collection, the largest outside Germany.

A number of these works are gifts of modernist pioneer Josef Albers (1888-1976), who, along with his wife, textile designer, weaver and printmaker Anni Albers (1899-1994), influenced generations of designers as both teachers and artists.

On view in six galleries are prints, paintings, photographs and weavings as well as practical projects such as furniture and designs for homes, dorm rooms, bedspreads, and utensils. What these diverse works have in common is a lighthearted, playful and inquisitive spirit. Some are studies by undergraduates in workshops led by the Bauhaus émigrés, experiments in fashioning images and tools that aspire to elevate and enhance daily life. Many are grounded in natural forms and hues and assembled from cast-off objects. Most have a fresh, timeless quality and invite a DIY impulse in viewers.

Take the captivating images by Ruth Asawa (1926-2013), who before becoming a distinguished sculptor was a student of Josef Albers at Yale, where he taught for decades. Using cut paper and molded newsprint, Asawa creates inventive, biomorphic forms that burst with energy.

The show includes works by both renowned and less-familiar artists. Near the Asawa prints are lithographs by Paul Klee.

The Bauhaus aspired to transform daily life through the power of design, from handheld objects such as dining utensils to entire buildings—if not cathedrals, then campuses and public structures. Harvard was a willing partner in the Bauhaus experiment, and commissioned the design of a center of residential life for its graduate students.

The Bauhaus founding director, architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969), became head of Harvard’s department of architecture in 1937. His firm, The Architects Collaborative (TAC), designed the graduate center. Now partly embedded within Harvard Law School’s new Wasserstein Hall, the 1950 Gropius complex features seven low-rise dorms surrounding a shared green. Conducive of community, the elegant and simple campus resembles Gropius’s Bauhaus site in Dessau, Germany.

Gropius commissioned original, site-specific works for the graduate center’s dining and lounge areas from fellow Bauhaus faculty, including Herbert Bayer (1900-1985) and Josef Albers.

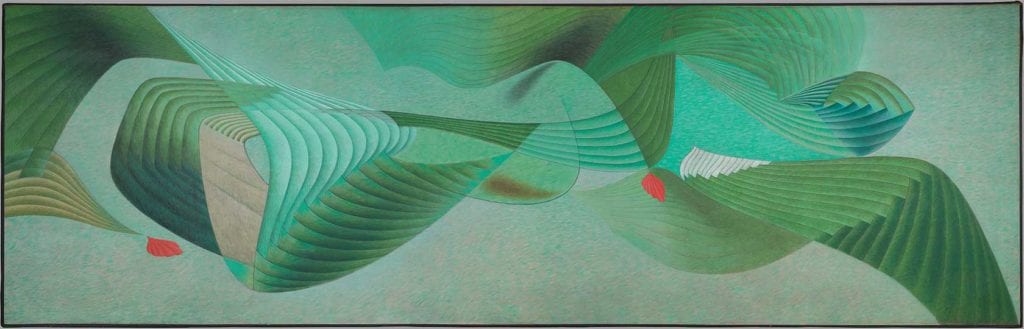

One of the most alluring works in the current exhibition is Bayer’s mural for the dining room, “Verdure” (1950), a panel more than eight feet high and 19 feet wide that evokes nature and water in fluid shapes rendered in myriad tones of green. In a gallery adjacent to the exhibition is another site-specific work for the graduate center, Hans Arp’s “Constellations II” (1950), an ensemble of wooden panels in amoeba-like shapes.

Unlike these works, the Josef Albers commission remains in the graduate center’s lounge, now incorporated into Wasserstein Hall, where it is visible to visitors.

The striking relief sculpture is a composition of light and shadow created by bricks stacked in vertical columns. Entitled “America,” the artist’s 1950 tribute to his adopted homeland celebrates what he heralded as the “vital, courageous movement upward” of skyscrapers.

His transformative use of ordinary materials is true to the 1919 Bauhaus manifesto by Gropius, on display at the entrance of the show in a woodcut designed by Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956), who headed the Bauhaus printmaking workshop.

In its soaring lines, angles, and curves, Feininger’s dazzling abstract image of a cathedral resembles Joseph Stella’s majestic “Brooklyn Bridge” (1919-20), another European immigrant’s homage to America. Feininger’s image accompanies the statement by Gropius that links Bauhaus aspirations with medieval and Renaissance achievements that united “the hands of a million workers” to forge structures of grandeur that uplift all.

In “America,” Albers honors skyscrapers as cathedrals of the New World. As they explored America, he and Anni also encountered earlier epochs as inspiration. They traveled often to Mexico, fascinated by the simple materials and strong forms of pre-Columbian sculptures and architecture, and brought back numerous artifacts they purchased from local children.

The exhibition represents Josef Albers mainly through works by his students that he gave to Harvard. But several wall hangings by Anni Albers are on view. These examples of what she described as “pictorial weaving” echo the earth tones and geometric forms of pre-Columbian pyramids and plateaus in complex, multicolor grids.

Geometric shapes are fundamental to the masterpieces of Josef Albers, who over decades of experiments with the interactions of color created more than 2,000 prints and paintings that he entitled “Homage to the Square.”

He engaged his students at Yale in such experiments to discover how both applying and combining colors can change the viewer’s perception of an image. Albers regarded colors as actors and the composition as a work of theatrical performance in which colors interact with each other and with the viewer. A successful image is alive, a dynamic entity that emits its own radiance.

Two books published by Yale University Press offer a rich introduction to Josef Albers. His iconic 1963 textbook, “The Interactions of Color,” abounds with examples along with his text, each a lesson that guides readers in viewing the images and crafting their own versions. “Josef Albers/Interaction,” a catalog of a 2018 Albers retrospective in Essen, Germany, combines biographic and curatorial essays with fine reproductions of the artist’s prints and paintings. Edited by Heinz Liesbrock, curator of the retrospective, the book follows Albers from his years as an apprentice in a stained glass workshop through his time at the original Bauhaus and his decades at Yale.

Also taking part in the worldwide Bauhaus centennial celebration is the MIT Museum, which through September 1 is presenting “Arresting Fragments: Object Photography at the Bauhaus.