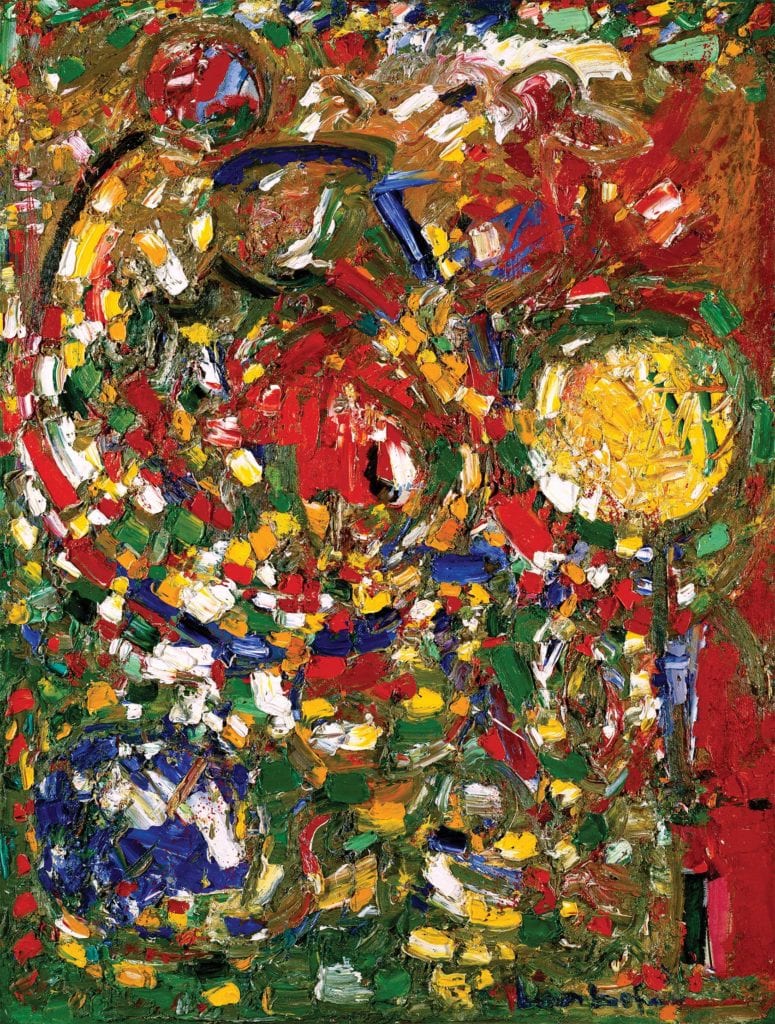

“The Garden” is an enthralling introduction to the exhibition of paintings by abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem through Jan. 5.

Not a depiction of a garden but rather an image with a life of its own, the 1956 painting’s multicolor swirls and dabs of pigment vibrate and glimmer in delirious profusion, creating a pulsing tapestry of color and light that immerses a viewer in an experience akin to gazing at a sunlit pageant of flowers. Made by Hofmann in the last decade of his life, the piece demonstrates the ideal he worked toward throughout more than six decades, first in Europe and then, from the 1930s onward, in the United States, both as an artist and educator. A painting, Hofmann said, is a composition in which all of its elements cohere to “vibrate and resound with color, light and form in the rhythm of life.”

The PEM exhibition, “Hans Hofmann: The Nature of Abstraction,” and its accompanying catalog, explore how Hofmann progressed over 60 years to achieve the distilled masterpieces that mark his later years. Honoring his equally important legacy as revered educator of artists, the show presents 47 paintings from 1934 to 1965 within the context of the principles that guided his career as a teacher, painter, and perpetual learner.

Born in Germany and immersed in modernist trends in Paris, Hofmann in the early ’30s became part of a generation of gifted European artists and scholars who migrated to the U.S. to escape the rise of Nazism between the world wars.

Former students who had studied with Hofmann in Europe invited him first to Berkeley, and three years later, to the East Coast, where Hofmann established art schools in New York City and in Provincetown after briefly teaching and painting in Gloucester.

By 1948, Hofmann was the subject of the first American show of a major abstract expressionist, a 50-year survey at the Addison Gallery of American Art entitled “Hans Hofmann, Painter and Teacher.” Such was the rich trajectory of his development that the Addison’s director, Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr., described the show as “a course in recent art history as experienced through one man.”

A decade later, in 1957, Hofmann left teaching and spent the last decade of his life painting. In 1963, he donated his most significant paintings to the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), where they form the world’s largest museum collection of his works.

Massachusetts, particularly its coastline, became an abiding part of Hofmann’s life and career, and PEM is a fitting place to host this exhibition, in which many works were inspired by the weather, dunes, and streetscapes of Provincetown.

PEM is the exclusive East Coast venue for the exhibition, organized by BAMPFA and the most comprehensive examination of Hans Hofmann’s innovative and prolific career to date.

Lucinda Barnes, Curator Emerita, BAMPFA, developed the exhibition and its catalog and organized the PEM installation with PEM Associate Curator for Exhibitions and Research Lydia Gordon. The 47 works draw from the BAMPFA holdings as well as works from private collections never before shown in a public venue.

The fully illustrated catalog widens and deepens the exploration of Hofmann’s evolution as an artist with searching essays that examine 70 of Hofmann’s paintings from 1930 through 1966, juxtaposing many with works by his predecessors and contemporaries. In her introductory essay, Barnes synthesizes Hofmann’s transatlantic life and career. Humanities scholar Ellen G. Landau focuses on Hofmann’s pivotal ’40s. The artist’s experimental approach receives a closeup by art historian Michael Schreyach, with illuminating comparisons among Hofmann’s formative ’30s still life studies and those of Cézanne, with whom Hofmann seems to be in dialogue as he tests the power of color to animate a canvas beyond just illustration.

The PEM exhibition translates this exploration into a succession of eight galleries. Honoring Hofmann’s dual distinction as an artist and educator, the galleries present paintings and wall texts that highlight the principles Hofmann applied as he conducted both pursuits.

“Nature speaks to us in space, color, and light,” Hofmann often said, emphasizing use of these elements to create “push and pull,” his signature phrase to describe the dynamism he aspired to inject into abstractions. He described his goal in a statement that Barnes quotes in her catalog essay: “Art must not imitate physical life. Art must have a life of its own—a spiritual life.”

Moving through the galleries, visitors can follow Hofmann’s lifelong process of progressively paring down, distilling and transforming images on canvas. His paintings evolve into compositions of colorful forms that seem to advance and recede in space, as, in an aquarium, fish float toward and away from the viewer.

A gallery entitled “In the Studio” presents Hofmann’s buoyant early still life “Apples” (1934) alongside Paul Cézanne’s “Still Life with Apples and a Pot of Primroses” (about 1890), each an experiment in using color to heighten shapes.

In other galleries, paintings show Hofmann using lines to form shapes rather than to illustrate objects, and demonstrate his embrace in the early ’40s of tools beyond the brush and palette knife. For Hofmann, like fellow artist Jackson Pollock, with whom he had a relationship of mutual admiration, painting was a physical act. He began dripping pigment onto his painting surfaces and rotating them to create serpentine swirls such as the whirling patterns of “The Wind” (1942). With splatters, drips and fingerprints, he applied varied consistencies of pigment to create surfaces alive with both texture and color.

The resulting images moved renowned painter-sculptor Frank Stella to describe Hofmann as “the artist of the century” who “produced more successful color explosions than any other artist.”

Encouraging audience participation, the exhibition’s Color Room invites viewers to immerse themselves in slowly mutating light and identify the emotions provoked by the shifting tones. At a Push and Pull activity table, visitors assemble their own compositions from colored shapes and observe the impact of their choices.

In 1957, Hofmann closed his art schools and turned to a full-time painting practice for the first time in more than 40 years. Concluding as it began, the PEM exhibition presents examples of his spectacular late works. Among them are “Indian Summer” (1959), “Nocturnal Splendor” (1963) and other visual poems evoking the stars, twilight, soil and, in “The Castle” (1965), an image of spiritual ascent.

Here, as in “The Garden,” Hofmann’s paintings speak for themselves, achieving a goal he described in a 1962 speech at Dartmouth College that Barnes quotes in the catalog: “My aim in painting is to create pulsating, luminous and open surfaces that emanate a mystic light.”