Maybelline Perez, 21, remembers how complicated it was to move her belongings from her home in East Boston to her dorm on Northeastern University’s campus without a family car.

Her brother Ben, 16, a boarding student in Andover, uses a combination of MBTA buses, subways and commuter rail to go between school and home, making what should be a 30-minute drive into a two-hour-long commute.

Perez and her family moved to Boston in 2012 from El Salvador. Since then, they have been living in the United States undocumented.

Having a driver’s license would allow the Perez family to take faster trips to Andover and to roam the state freely.

“It’ll be easier to have a mode of transportation to go see [Ben] more often or whenever he wants to come back home,” said Perez.

Undocumented immigrants in Massachusetts cannot currently obtain a driver’s license. They risk deportation if they are stopped while driving, and must rely on public transportation and rides from friends and family to get around.

For more than a year, there has been a greater collective effort among state legislators, activists and individuals to create a statewide change to this policy.

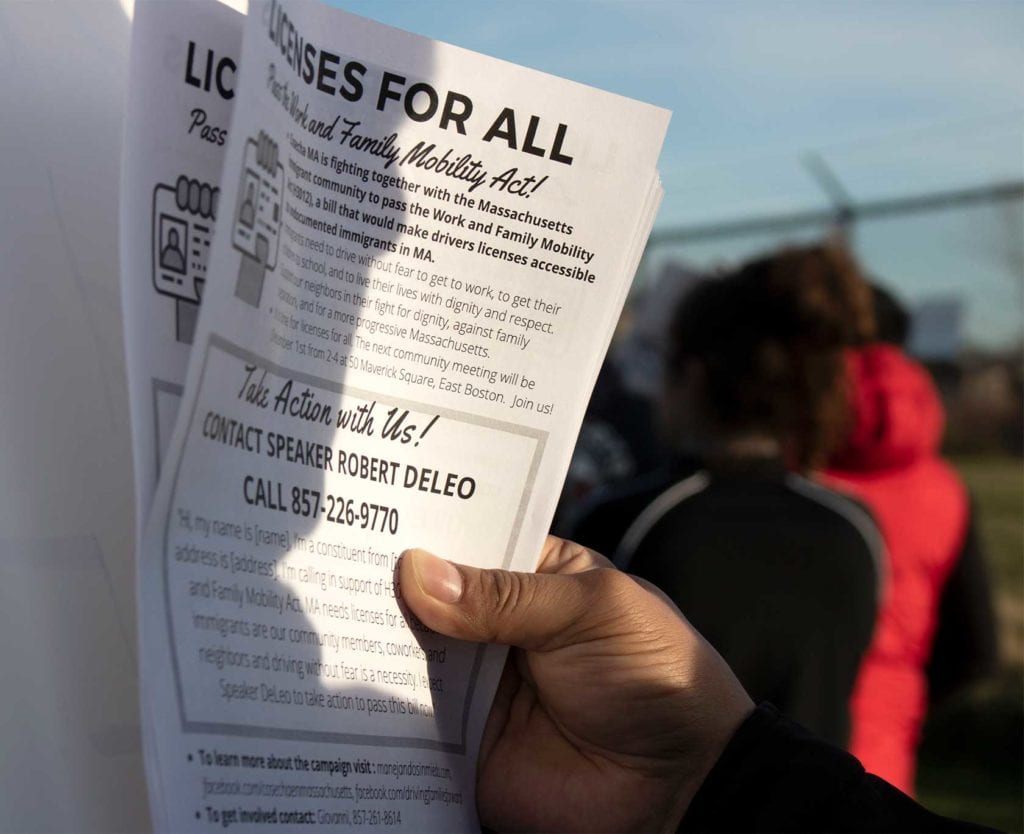

The Work and Family Mobility Act, Senate Bill S.2061 and House Bill H.3012, would rewrite current law and enable any resident of the state who is eligible to obtain a driver’s license to get one, regardless of immigration status. These licenses will not comply with federal “REAL ID” requirements but will allow immigrants to drive in the state legally.

Thirteen states, as well as Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C., have implemented licensing programs for undocumented immigrants. New York most recently approved legislation to provide driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants, and Massachusetts could be on its way to becoming the 14th state to do so.

The bill was first introduced 15 years ago by Boston Mayor Martin Walsh when he was a state representative. Legislation has languished for years, according to state Sen. Brendan Crighton (D-Lynn) who heard of the bill when he was a staffer under former Sen. Thomas McGee (D-Lynn) during McGee’s time as co-chair of the Joint Committee on Transportation.

Crighton is now the main senator sponsoring the bill, which was re-introduced in January 2019. “It is an honor for me to fight for folk being harmed for no reason,” said Crighton in a phone interview.

The immigrant and foreign-born community make up almost one-third of Crighton’s constituents in Lynn. He met with many community members while he was getting ready to file the bill. They expressed the difficulty brought into their lives by this issue. “Children rely on their parents to drive them to school,” said Crighton. Immigrant parents also struggle to make it to school events, visits to the doctor and their jobs.

In Massachusetts, the total foreign-born population in 2017 was nearly 1.2 million, or 16.9% of the total population. Around 185,000 residents, or almost 3% of the population, are undocumented.

Matt Cameron is an East Boston-based lawyer who represents undocumented immigrants. He has worked with Mexican dairy farmworkers in Vermont, where they can receive driver’s privilege cards, a driver’s license that does not comply with REAL ID, a program that rolled out in 2014.

“They’re already a part of our society, they’re already paying taxes, they’re raising their kids here and they’re going to church, going to school, doing all the things that we do and they’re already driving,” said Cameron.

Many of Cameron’s clients already drive and carry the only form of identification they have, which is typically a government-issued passport from their native countries.

Cameron supports the bill because it would give his clients a form of identification that can be used legally for driving. “A passport is too dangerous to carry around all the time,” he said.

While many immigrants and activists see this as a human rights and protection issue, the bill also addresses public safety concerns. Safety on roads will be improved if this act is passed since licenses can only be issued to residents who meet road and vision test requirements, said Crighton.

“Driving has nothing to do with who they are or where they are from,” he said.

Immigration and the lives of immigrants are constantly debated, and when it comes to the Work and Family Mobility Act, the situation is no different.

In January, the Boston Herald reported that Gov. Charlie Baker plans to veto any bill that would allow licenses for undocumented immigrants.

At the bill’s public hearing on Beacon Hill early in September 2019, House Minority Leader Bradley Jones (R-North Reading) said, “It’s a wrong policy. It’s rewarding people that are here illegally,” as reported by Thomas Grillo for Itemlive.com.

Opponents of the bill also believe that issuing an ID like a driver’s license will give undocumented immigrants the ability to commit voter fraud or gain access to benefits only available to citizens.

While legislators are advocating from the State House, activists and leaders from organizations and centers around Boston and the state are creating movements and efforts to inform their communities about the bill and taking action to make their voices heard on the state level.

Natalicia Tracy is the executive director of the Brazilian Worker Center (BWC), a social and economic justice nonprofit organization for working immigrants in Greater Boston. Together with SEIU 32BJ, BWC co-chairs Driving Families Forward, a campaign and coalition of dozens of organizations formed with the purpose of advocating for the Work and Family Mobility Act.

“Working with BWC we saw a lot of issues all the time, and we hear in the courthouses encounters with the police [that] have to do with driving without licenses,” said Tracy, “and we thought, ‘Why don’t we work on this?’”

The BWC was contacted by state Rep. Christine P. Barber (D-Somerville) in mid-2018 to work together on possible administrative change in regards to licenses. By October 2018, Barber and the BWC came to an agreement about collaborating on a bill that was later filed in January 2019.

Tracy then reached out to 32BJ in Boston, a branch of the Service Employees International Union, to see if they would be interested in joining the efforts since many of their union members are undocumented immigrants who would benefit from the licenses bill. Now the two teams work weekly on campaign strategies, fundraising, organizing and meeting with campaign consultants.

On Nov. 19, Driving Families Forward held a final lobbying day at the State House for the current legislative cycle. The day started with a series of speakers including doctors, insurance agents and members of the immigrant community. Crighton and Barber were two of the keynote speakers.

“I’m sponsoring this bill because constituents of mine from The Welcome Project, which is a local organization in Somerville and Medford that works with new immigrants, came to me and said this was the most important priority for them and suggested this,” said Barber in an interview.

Among the speakers was Maria Rodriguez, a Salvadoran resident of Ayer and a Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipient. The town of Ayer does not have public transportation. She has to commute to Boston every day using the commuter rail, which makes for an hour long commute. A commuter rail monthly pass for Rodriguez costs $388 while a regular round trip is $24.

Under TPS, she was able to get her driver’s license, but with President Trump threatening the viability of this program, her future in the country is uncertain.

“If they remove TPS, I end up without a license and everything ends up in the air and we end up with nothing. We are left without any benefits,” said Rodriguez after the lobbying day. “We have 20 years living here; we deserve licenses and residency. I have been living here for almost 20 years and I have been paying taxes ever since.”

Another organization on the frontlines of the Mobility Act is Movimiento Cosecha, a nonviolent movement working to win permanent protection, dignity and respect for the 11 million undocumented people in this country. Cosecha is a decentralized national organization with a network of different activist groups working on specific causes related to immigration in their respective cities and states.

In Massachusetts, there are Cosecha circles in East Boston, New Bedford, Lawrence, Worcester and many other cities, individually and collectively fighting for driver’s licenses through sit-ins, marches and other forms of organizing.

Just before Thanksgiving, Cosecha leaders from the East Boston branch led dozens of demonstrators through Winthrop, home of House Speaker Robert DeLeo, to call on the Democratic leader to show support for the bill.

Giovanni Miranda, a resident of Malden and an immigrant from El Salvador, is one of the local leaders of Cosecha in East Boston. His identity as an immigrant motivates his work as an activist.

“We have a lot of necessities as the immigrant community,” said Miranda, “and one of those is getting licenses. As an immigrant myself, I need a driver’s license.”

Years ago, Perez’ father had a job that required a long commute. Now, her parents work in East Boston and Downtown, so transportation is less of an issue. Even then, Perez addresses the necessity of a driver’s license.

“It brings more normality to your life,” she said.

The Joint Committee on Transportation has set Feb. 15 as a deadline, which means from now until then, the bill can be sent back for revisions or moved forward, according to Sen. Crighton.

This article originally ran in The Scope, a project of Northeastern University’s School of Journalism.