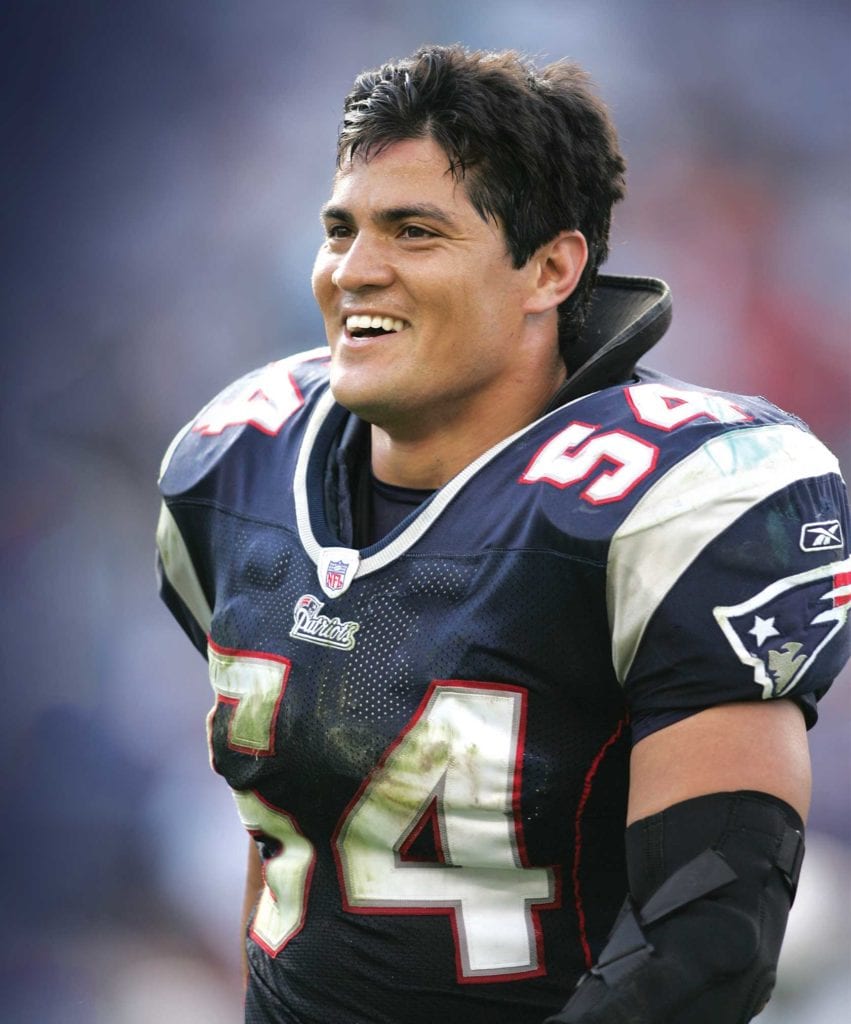

It seems Tedy Bruschi just can’t get enough of football. It all started when he was 14. Although he dabbled in track, it was football that won his heart. “I fell in love with it,” he said.

That passion led him to letter in high school football and rack up accolades at the University of Arizona. In 2013 Bruschi was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame as a defensive end.

In 1996 Bruschi was selected for the New England Patriots as a lineman, and proved his merit. In his 13 seasons with the Patriots, Bruschi played in 189 games and scored 1,134 tackles.

Bruschi, 46, is still tackling … but a different opponent.

It all started one night in February, 2005. He woke up in the middle of the night with a severe headache and weakness on his left side. He attributed the symptoms to a particularly tough game two days prior. “It was not unusual to wake up in pain,” he explained.

Bruschi did what many people suffering the symptoms of stroke do. He went back to sleep, but when he awoke the next morning, he was worse. “I couldn’t see,” he said.

When you put it all together, he experienced some of the classic symptoms of stroke — severe headache, weakness on one side, vision impairment. It’s the loss of peripheral vision that got his wife’s attention. She called 911. Bruschi was taken to Massachusetts General Hospital, which is designated as a comprehensive stroke center by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. MGH is also the hospital affiliated with the Patriots.

Thinking back, Bruschi admits that he did not recognize the symptoms of stroke. He associated that word only with a swing at a golf ball. Scans confirmed the diagnosis. The neurologist placed a hand on his shoulder and uttered just five words he wasn’t expecting to hear. “You have had a stroke,” the doctor said.

Bruschi suffered an ischemic stroke, which is attributed to a blockage in one of the arteries feeding the brain. Because of the delay in treatment, he was not eligible for the administration of clot busters, which are medications that can stop a stroke or lessen its impact.

Initially the diagnosis did not resonate with Bruschi. He always associated that medical condition with advanced age. He was 31 at the time. But what could have caused a stroke in a young person in prime health and sound physical shape? Bruschi said he had no risk factors of stroke. His blood pressure and cholesterol were normal. He had no history of diabetes or heart disease.

The doctors discovered he had a hole in his heart, a condition known as “patent foramen ovale” (PFO). During fetal development this hole normally exists between the upper chambers of the heart called the atria. Soon after birth it closes. In roughly 25 percent of the population, however, it remains open, and often poses no problem.

PFO, however, may actually be a hidden risk factor of stroke, and accounts for a high percentage of cases of cryptogenic stroke, or stroke of unclear cause. The incidence of cryptogenic stroke is on the rise in young people. The hole in Bruschi’s heart has been closed, but a repair is not an absolute protection against another stroke.

Bruschi spent three days at Mass General and underwent extensive rehabilitation at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital.

But then Bruschi did something that few people — including Bruschi — saw coming. He returned to football, and played four more seasons with the Patriots before retiring in 2009.

His life has been busy since then. He is an NFL analyst for ESPN. He founded Tedy’s Team, a foundation that raises funds for stroke awareness and research. He remains a spokesperson for the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association.

Bruschi keeps himself in football-playing shape. He eats fruits and veggies, avoids red meat and drinks plenty of water. “That’s my way of still playing defense,” he explained. “I keep myself in shape.”

On July 4 of this year Bruschi suffered another stroke. But here’s the good news. Though unexpected, he recognized the symptoms immediately. He called 911, and was admitted to a local hospital. This time it was a transient ischemic attack (TIA), known as a mini-stroke. He experienced weakness in his left arm, had a facial droop and slurred speech. The symptoms of a TIA are temporary. He was discharged after a one night stay.

It is possible that Bruschi has a blood clotting disorder called protein S deficiency, a rare cause of recurrent ischemic stroke in the young population. He is on a blood thinner to reduce the risk of recurrence.

While he may never know the exact cause of his strokes or if he is exempt from another, that’s not the real issue with Bruschi. He can’t attack an enemy he does not see.

“Just know the warning signs of stroke,” he advises. “If you learn them, that’s all you can do.”