Black and white and political all over

Zanele Muholi’s self-portraits challenge race in visual history

“Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness,” an exhibition of photographs by Zanele Muholi at Harvard’s Ethelbert Cooper Gallery, is an art history textbook painted black. The series of more than 80 self-portraits of the artist challenges race and representation in visual history in striking and beautiful way. The show is on view through June via virtual tour on the Cooper Gallery website.

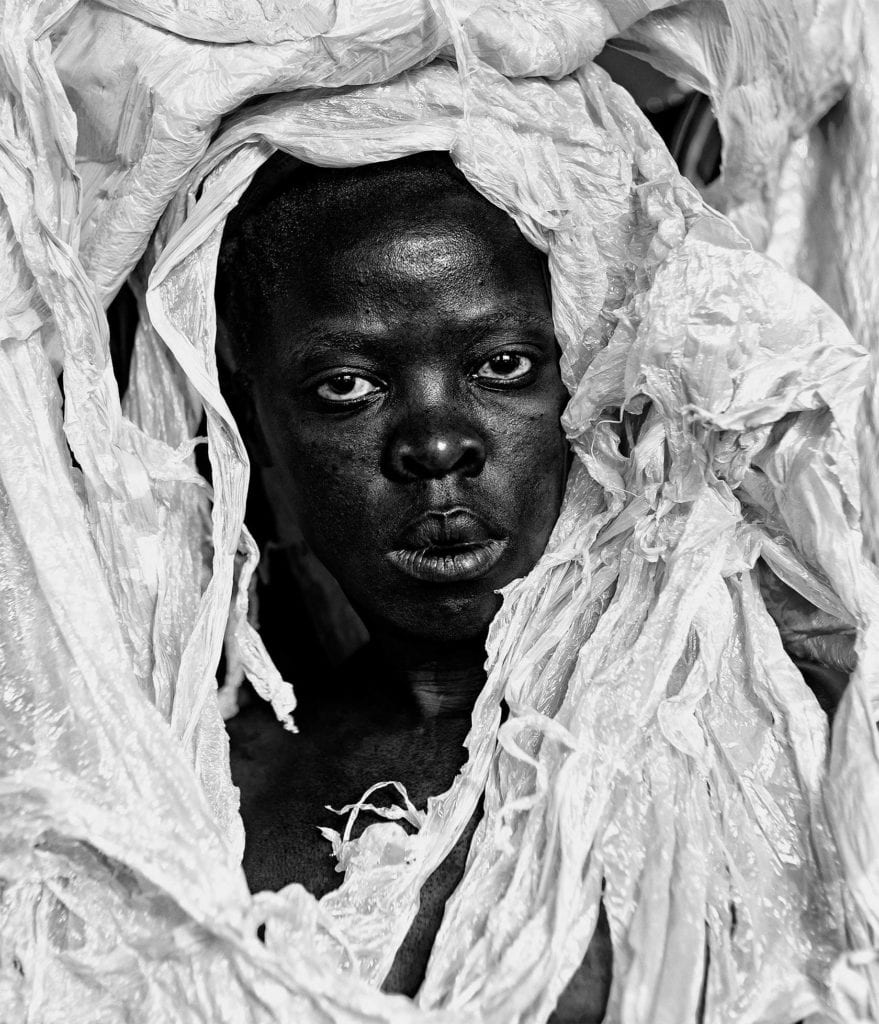

Somnyama Ngonyama II, Oslo, 2015. © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

“Visual activism has a lot to do with two things, connecting the visual and my activism. Which means that every image that I take has a lot to do with politics. In my work I’m pushing a political agenda,” says Muholi in a video conversation with the Seattle Art Museum. “The aim of this series is to undo racism in the media, in mainstream spaces.”

Aesthetically, the black and white portraits are breathtaking. The stark color contrast and textures of the images draw viewers in. On further inspection it becomes clear that the props used to make hairpieces, headdresses and garments are everyday items like pens, cardboard, clothespins and vacuum tubing. Each of these objects is tied to an instance of social, economic or environmental injustice — or sometimes, all three. Muholi uses these everyday objects and poses from famous paintings in the Western canon to expose centuries of violence, disenfranchisement and fetishizing of black cultures and people.

In photographs taken in Japan around Bonsai trees, Muholi points to the cultural appropriation and environmental disruption of removing these trees from their natural habitat to be taken to other parts of the world. Muholi’s black body in this space is also pushing a question, what about the Afro-Japanese populations that are never represented in mainstream culture?

In “Kwanele, Parktown, 2016” Muholi’s face emerges from a heap of ripped white plastic. Her expression is angry, defeated and tired. This is the plastic often wrapped around suitcases while traveling to prevent bursting suitcases from opening. Muholi is referencing how it feels for dark-skinned individuals to cross borders with the additional hoops and scrutiny they find themselves facing. “Sometimes you feel like trash,” they say. “You feel like the same plastic that covers your suitcase.”

In portraits where Muholi wears an elaborate necklace of cowrie shells or a footstool as a crown, the artist references the exoticism placed on African cultures. In historical Western portraits of foreign countries, people are painted and labeled as “other” in similar styles. “Ntozabantu VI, Parktown,” shows Muholi wearing a plastic tiara on their piled-high hair and staring directly into the camera. Here they’re alluding to beauty pageants, such as Miss World, which South African women were not allowed to enter prior to 1970.

“With this work, people will see that it’s possible that the gallery is meant to be for everybody and not for a select few and also to engage in a mature and constructive way,” says Muholi. “We don’t have many of us in these spaces, but it’s possible.”