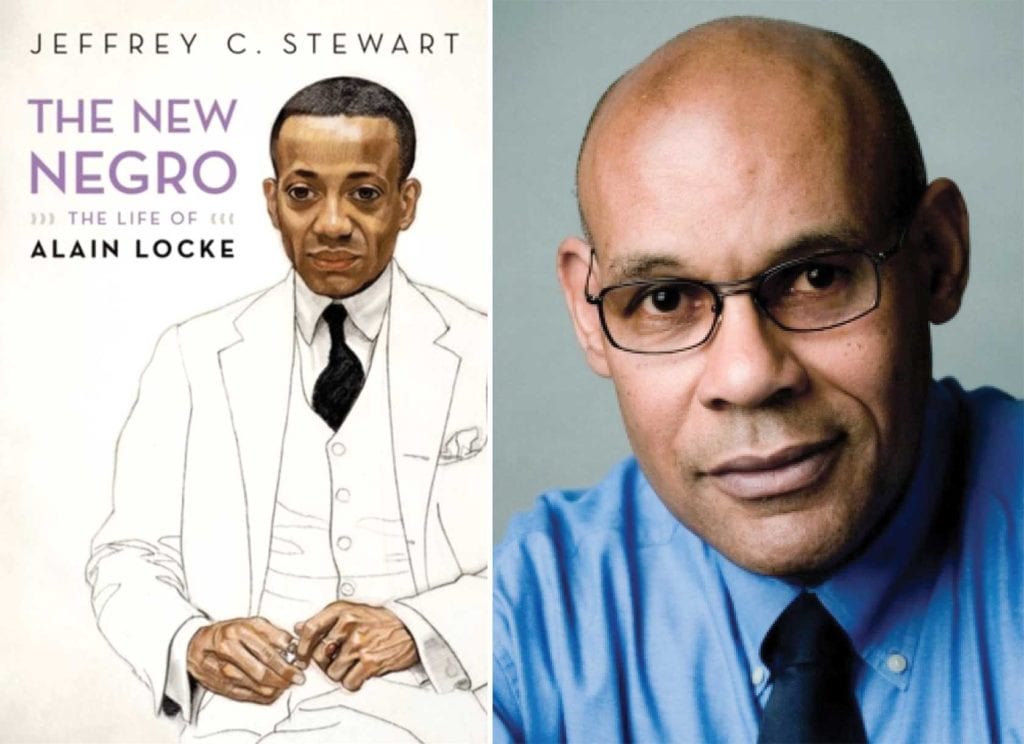

Jeffrey Stewart’s ‘The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke’ looks to past to shed light on present

Last Friday, the Banner sat down virtually with Jeffrey Stewart, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography “The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke,” to discuss all things Black power and aesthetics, from Alain Locke’s contribution to the Harlem Renaissance to Megan Thee Stallion’s “Saturday Night Live” performance.

What made you feel compelled to tell Alain Locke’s story? And why now?

Well, I was first introduced to him in graduate school and found him to be a compelling figure I couldn’t get away from. Locke was interested in what Black people could find within themselves, within their own culture and heritage, to propel them forward and fuel an internal revolution. That, he said, would be the New Negro. Not the negro, created as a figment of the white imagination, but someone who had reinvented herself or himself based on this cultural heritage and sense of efficacy. I was particularly struck with this after the ’60s and coming into the ’80s, because it seemed like we were set back so much in terms of the political revolution that we had thought was going to clear away racism once and for all. In fact, we realized it was a counterrevolution to keep us from going too far. So at that moment, it seemed important to me to explore alternative platforms to the political.

Alain Locke is, of course, one of the fathers of the Harlem Renaissance, and as such has been written about and studied by many other scholars. What new perspective do you bring to his story and work?

My initial perspective was from growing up in the late ’60s. I look back to understand the present and now realize this book also tries to help us understand the future. Locke predicted that black people would develop cultural discursive power through the arts, and that’s somewhat the case today. Beyoncé has a tremendous amount of cultural power. Megan Thee Stallion critiqued [Kentucky] Attorney General Cameron on “Saturday Night Live” for legitimating the murder of Breonna Taylor. Artists are powerful political forces. I think if Locke were here today, he would see that black popular music and culture has become a platform of emancipation in a way it couldn’t be in the 1920s. So I was fascinated with looking back to understand the period I was in, and then having something to say to the 21st-century youth. Particularly that you are subjects, you are powerful, you are the driving forces of American aesthetics.

A side of the Black experience that sometimes is not emphasized is our creativity as power. You can extend Locke further when looking at the Black Lives Matter movement. There’s a performance art to how Black Lives Matter has staged protests. There’s an aesthetics even in a political protest. I think Locke would have wanted us to think about that as well.

That was going to be my next question for you. How do you think Locke’s theories on the New Negro apply to the Black Lives Matter movement today?

Yes, I see the Black Lives Matter movement drawing on black aesthetics. There’s been a lot of performers and artists who have taken up media as an important part of liberation. How you structure media, how you reach people on an emotional level as well as a critical, intellectual level is very important. So Locke would encourage us to look at our experience aesthetically as well as politically and then try to use that aesthetic observation to strengthen our political and social efficacy.

I’m interested in your construction of the story of his life. Is the story you ended up telling the same one you set out to tell at the beginning of your process?

No, I don’t think so. I began with the concept of cultural tourism, then realized the more important idea was, how do you survive as a Black thinker in 20th-century America? You have this education, yet you’re not admitted into elite spaces. And you have been educated away from your community such that you no longer fit into it. The other thing which became central is his queerness. For Locke, sexuality was another form of marginalization, even within the Black community. But I didn’t want to reduce his story to his sexuality, so the challenge was to keep all his subjectivities in play. He was a Black man, an elitist, a misogynist. He had a difficult relationship with women who weren’t his mother. And he was part of a group of gay men who felt they were in competition with women, particularly black women, within this cultural sphere. But he also promoted Zora Neale Hurston, so there were contradictions whenever I would come up with some map of his personality. I had to keep redrawing it, which was one of the challenges of the book.