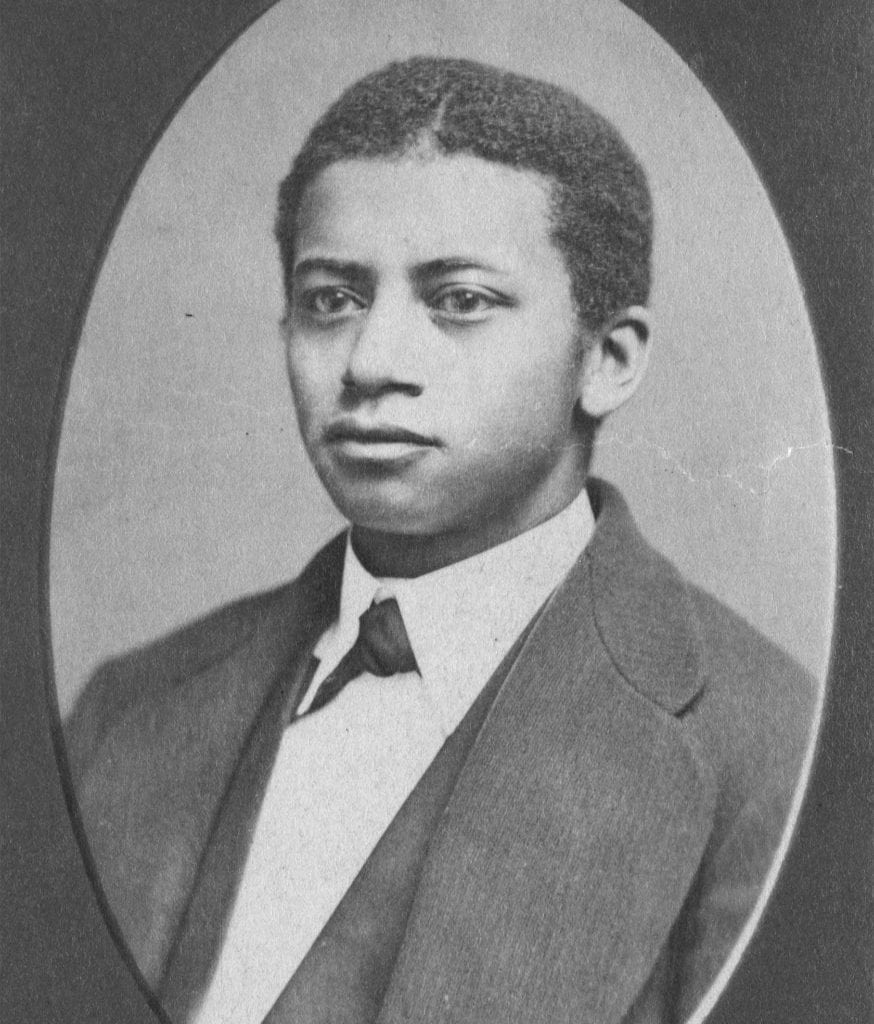

Dr. George Franklin Grant: defying the odds in 19th century Boston

One of the few African Americans who practiced dentistry in late 19th-century Boston, Dr. George Franklin Grant earned a reputation for exceptional skill in bridge work. The son of Phillis Pitt Grant and Tudor Elandor Grant, he was born on September 15, 1847, in Oswego, New York. There, his father made a living as a barber. At the age of 15, George Grant undertook an apprenticeship in dentistry under Oswego dentist Dr. Albert Smith — first as an errand boy and later as a lab assistant. Thereafter, in 1867, he traveled to Boston to attend Harvard Dental School.

In 1870, the same year that Richard Theodore Greener became the first Black graduate of Harvard College, Grant graduated from Harvard Dental School with distinction, becoming the second African American to acquire the degree of Doctor of Dental Medicine. The first, by the way, was Dr. Robert Tanner Freeman, who graduated from the dental school the previous year and decided to establish his practice in Washington, D.C. Harvard Dental School professor Luther D. Shepard praised Freeman as “the peer of any as a student and gentleman.” He said, “His name is in history as the first of our alumni to be starred, he having received many honors in dentistry.”

Grant was a first as well. He was Harvard Dental School’s first black faculty member. He taught there as an assistant in its mechanical department from 1871 to 1874, and as a demonstrator in mechanical dentistry from 1874 to 1883. Then, the dental school promoted him to instructor in the treatment of cleft palate and cognate diseases — a position he held until 1889. Grant also conducted a dental practice at 86 Pinckney St. in Boston’s Beacon Hill community. Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot was one of his private patients.

Dentist, leader, inventor

Grant occupied positions of leadership as president of the Harvard Dental Alumni Association in 1882 and as a founding member and later president of the Harvard Odontological Society. A leading authority in the field of dentistry, he presented a paper titled “Mechanical Philosophy as an Element of Dental Education” before the Massachusetts Dental Society on June 3, 1880, at its 15th semiannual meeting. In October 1887, Grant was awarded a medal at the International Medical Congress. And after accepting an invitation from the British Dental Association, he gave a demonstration in the treatment of cleft palate at their annual meeting in Dublin, Ireland, in August 1888.

Boston civil rights Attorney Butler R. Wilson, Grant’s contemporary, described him as “one of the most competent and best known dentists among the younger members of the profession.” But Grant was not only a popular dentist. He was an inventor as well. He created and patented the oblate palate, a prosthetic device used in the realignment of cleft palates. And in 1899, having developed a love of golf at the public golf course at Franklin Park, Grant invented and patented the wooden golf tee. His invention raised the golf ball slightly off the ground, giving the golfer greater control of his club and the direction and speed of his drive. The U.S. Golf Association belatedly recognized Grant in 1991 as the original inventor of the wooden tee.

Love and loss

In 1874, Grant married Georgiana H. Smith, the daughter of former state Representative John J. Smith, and they moved to 39 Sacramento St. in North Cambridge, Massachusetts. She gave birth to five children, however, only two survived to adulthood: daughters Maybelle and Theodora.

In November 1889, by then a well-to-do dentist, Grant purchased the former Beacon Hill residence of Boston Globe editor and publisher Charles H. Taylor, situated at 108 Charles St. After having endured more than his share of personal misfortune, the dentist lost his beloved wife, Georgiana, about two years later to typhoid fever. She was only 38. A widowed Grant eventually married Frances “Fanny” Bailey, a 25-year-old Virginia native, in 1894, and they were blessed with two more daughters: Frances in 1895 and Helene in 1897.

Despite having suffered great personal loss with the premature deaths of three of his children and his first wife, Grant was a kind-hearted man. At times he treated patients who weren’t able to pay for needed dental care. When they thanked him, as they often did, he would earnestly advise, “Now, don’t say anything about it! Do your work as well as you can, and be kind; that will be the best reward you can give me.”

Grant died of liver disease on Aug. 21, 1910 at his vacation home in Chester, New Hampshire.