When the emergency vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna started making the rounds, so did sensational headlines about how the Black community wouldn’t take it. Discussion arose among the medical community on how to convince Black people to get the vaccine, and organizations in Boston mobilized to get the community to the mass vaccination site at the Reggie Lewis Center.

But spread of the “hesitancy” due to cultural beliefs, myths and attitudes may have overshadowed the real issues that stop people from taking the life-saving shot.

All kinds of people are afraid to take the vaccine, and Black people are not the largest group of dissenters. According to an extensive survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation, only 10% of Black respondents said they would “definitely not” get the vaccine, while 24% responded they would “wait and see,” compared to 15% of white people who said, “definitely not” and 16% saying “wait and see.”

They found that 55% of Black people want to get it as soon as possible or already have. When looking at political affiliation, 29% of Republicans definitely do not want to get it, the highest among any race, age or political demographic — and most Black people are Democrats.

If medical experts, community leaders and political analysts were concerned about Black people declining the vaccine, what motivates the community to get it? For Thaddeus Miles, it was all the death he saw around him, and the overwhelming truth about the safety of the vaccine.

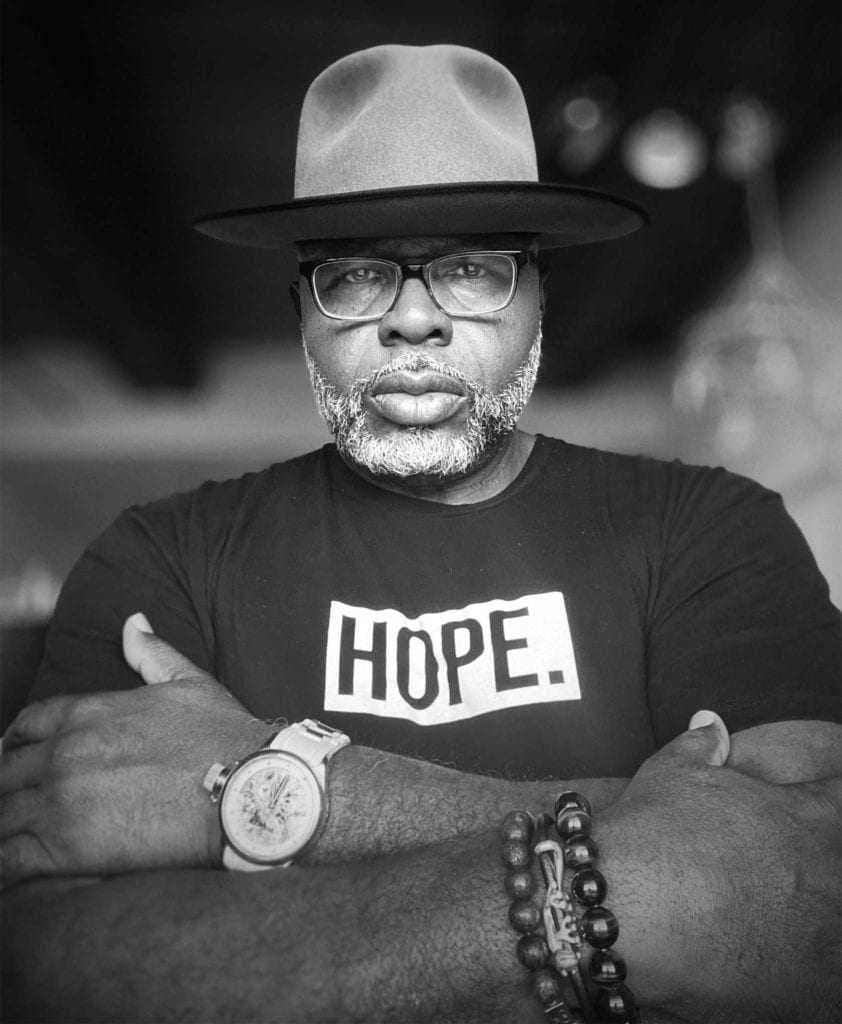

Miles is a Black man from Virginia, who has lived and worked in Massachusetts for 25 years. He now works in downtown Boston as director of community services at MassHousing, is a published author, and a photographer capturing Black joy in a time of unprecedented struggle.

When he heard about the vaccine, he said, “I’m not taking that!” For him, it came about way too fast. They couldn’t have cooked something up so quickly that could prevent severe illness and death from a virus he found out about just over a year ago.

At first, and for a long time, Miles agreed with the false narrative that many Black people haven’t and won’t get the virus, therefore he didn’t have to worry about getting it either. “That’s a white people disease, that’s not something for us,” he said to his friends.

Even when Robert Lewis Jr., founder of the BASE and well-known youth advocate in Boston, nearly died from COVID-19, Miles still wasn’t sure. “I didn’t know that he had it until I got a phone call and a text that said, ‘We’re gonna have a prayer service for Robert.’ And we got 300 people on Zoom.”

Miles admits he’s not the most trusting of federal government organizations. The Tuskegee Syphilis experiments on young Black men are a sore point for him. He’s aware of the history of racist medical biases against Black people, like assuming their nervous and immune systems can handle more than those of other races. “If they gave me a million dollars, there is no way that I’m taking this vaccine. That was my initial response and was my response for quite some time,” Miles said.

Later, Miles found out that 12 of his extended family members died from COVID-19 related causes. Hearing this news from his mother began more serious conversations about the effects the virus was having on his community. “I called her, she was crying and she was saying that the next door neighbor and her brother were in the hospital with COVID, and then the brother died,” he said.

“And then two days later, my eldest sister sends me an obituary. She’s like, ‘This is our cousin Champ.’” Champ is just two months younger than Miles.

Miles’ mother has four comorbidities, he has a younger sister who has dealt with cancer, and he has high blood pressure and an enlarged heart.

That youngest sister goes to church with one of the doctors at the forefront of COVID-19 vaccine development, a Black woman. “The church had a private Zoom webinar with her. And so my sister started quoting all of his data, which you know you have now, which is real, but also talking about the fact that they didn’t just start working on COVID,” he said.

Miles was able to be open with himself and his family about his true fears. Would he ever be able to see his mother again? Would he be able to hold her hand if she got sick? Would he leave the earth before his mother does, if he got the virus?

The choice became simple. “I may not be here in 10 years or 20 years, but I can live my life the way I want to live it now, by taking this vaccine,” he said.

Plus, he’d rather be sick for 24 hours with side effects he might not even get, than be sick for 24 days in the hospital with COVID-19. Getting sick with the virus can also compound the social causes of racism: disparities in wealth, healthcare and mental illness.

After dealing with his sister’s cancer, Miles’ family was able to have more vulnerable conversations about health. It’s that vulnerability that helped him make the decision to get the shot. “Even as a grown Black man, I can cry to my two sisters and mom. I don’t have to be Mr. Tough Guy, I don’t have to put on the fake mask around them about COVID,” he said.

Miles is now fully vaccinated from a shot that is approved by the FDA for emergency use only. He didn’t experience any side effects when he got his second dose. Both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines require two shots to reach full efficacy, while the Johnson & Johnson requires one, but all of them are very effective at preventing illness and even better at preventing hospitalization and death from the virus.

“[Now] when I talk to folks, I talk to them about how I wanted to live.”