Council to take up redistricting

With 87,000 new residents, city’s district lines are bound to shift

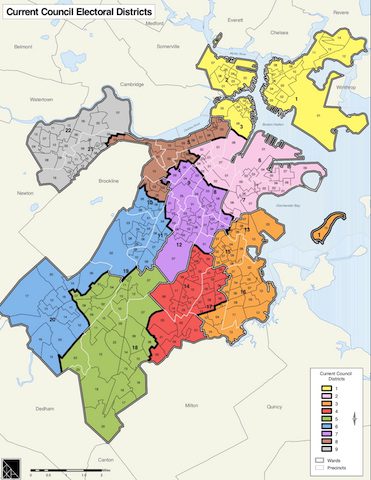

When the City Council embarks on its decennial process of redrawing political boundaries, the concerns of incumbent councilors and residents of the city’s 18 distinct neighborhoods often come into conflict with the body’s mandate to draw nine districts of relatively equal population.

“The goal is to create district lines that represent the population of the city of Boston without diluting any one group’s power,” says Redistricting Committee Chair and District 5 Councilor Ricardo Arroyo.

The U.S. Census Bureau will release population data in September. After that happens, the City Council will begin the process of re-drawing district lines to reflect changes in Boston, a city that has absorbed an estimated 87,000 new residents since 2010.

Each of the city’s nine council districts must have roughly equal populations in order to reflect the principle of one person, one vote. Because neighborhoods such as the Fenway and Chinatown have added housing units and residents at rates higher than neighborhoods such as West Roxbury and Hyde Park, some districts will lose precincts while others will gain.

For voting rights activists, the main principle is that should guide redistricting is that distinct population groups should have representation on legislative bodies. For decades after the nine City Council districts were drawn, just two district seats were occupied by Black people: District 4 in Dorchester and District 7 in Roxbury. When the districts were drawn in 1981, the majority of the city’s Black community was in those two districts, pointing to a practice referred to as “packing.”

Now, with a city that has more people of color than whites, the Council is majority people of color and the city is poised to for the first time elect a mayor who is not a white man.

Still, how districts are drawn matters. For decades now, Chinatown has been part of District 2, which is centered in South Boston and has always been represented by a South Boston resident. With increased population in both South Boston and Chinatown, will the latter remain in District 2?

Chinese Progressive Association Executive Director Karen Chen said it would be best for the neighborhood to be paired with other neighborhoods with similar political interests.

And as for joining the predominantly African American District 7?

“We would be open to it,” Chen said.

There are other neighborhoods facing similar dilemmas. In District 6, where three candidates are vying for an open seat, the more conservative and predominantly white West Roxbury shares political boundaries with Jamaica Plain and part of Mission Hill, home to some of the most progressive white precincts in the city. The district has not yet had a Jamaica Plain native elected to represent it.

Because the pace of homebuilding in both neighborhoods hasn’t matched the construction boom in the city’s downtown neighborhoods, it’s unlikely that the District 6 boundaries will change radically.

But the overall goal, Arroyo says, is to draw districts in which all residents feel like they’re fairly represented.

“If you do this correctly, you end up with a map that reflects the city of Boston’s communities,” he said.

North of Boston

At the state legislative level, activists in communities of color have turned their attention to the First Middlesex and Suffolk District, currently represented by Joseph Boncore, who is vacating the seat.

The district includes the Cambridgeport neighborhood of Cambridge along with Chinatown, Beacon Hill, much of Downtown Boston, all of East Boston and Revere. The district is currently just 38% people of color, but activists say that by adding in Chelsea and cutting out parts of Revere or Cambridge, the district could become majority people of color.

“We have a history of working on the same issues with East Boston and Chelsea,” Chen said.

If activists have their way, the First Middlesex and Suffolk District, long represented by Italian Americans, would be an easier win for a candidate of color.

But it’s census data that will provide the answers activists need to better advocate for new district boundaries, cautions Cheryl Crawford, executive director of MassVOTE.

“We’re looking at drawing districts that build power for people of color,” she said. “But you don’t start drawing lines without doing a deep dive.”

Boston District 1 City Councilor Lydia Edwards, who lives in East Boston, isn’t waiting for the new boundaries. She’s indicated her interest in running for the state seat and has $138,000 in her campaign war chest. And as city councilor, she’s already been elected to a majority white district, which includes Charlestown and the North End.

A troubled history

Back in 2000, the redistricting process grew contentious when activists accused white lawmakers who draw state and congressional district lines with diluting the power of Black and Latino voters. The House Redistricting Committee removed precincts in the predominantly Black sections of Codman Square from the district of House Speaker Thomas Finneran, adding in predominantly white precincts from Milton.

When questioned in court, Finneran testified that he had no knowledge of the committee’s work, an assertion that was later contradicted by emails in which Finneran had indeed communicated with committee members about the redrawing of his district. Finneran stepped down from his seat in the majority-Black and Latino district in the aftermath of the revelation.

During the 2010 process, House members drew districts more favorable for candidates of color, including a redrawing of the 7th Congressional District that made it easier for U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley to win.