‘Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities’ at RISD Museum

Sixty works cover artist’s early career

Within images no larger than a page in a notebook, Pakistani American visual artist Shahzia Sikander tells stories that bear witness to her times. Like the centuries-old manuscript paintings that inspire them, her works are crafted with intense rigor and often seethe with detail.

Based in New York City since 1997, Sikander, 52, works in media that include drawing, painting, printmaking, animation, installation, and performance and video. Her early drawings dominate the riveting exhibition, “Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities,” on view through Jan. 30, 2022, at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum in Providence.

Shahzia Sikander, “The Scroll II” 1991. Courtesy of Munazzah and Tariq Malik. PHOTO: Courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

Organized by Jan Howard, curator of prints, drawings and photographs at the RISD Museum, this exhibition explores the first years of Sikander’s career and accompanies images with indispensable wall texts. Its 60 works, most from 1986 to 2003, include many never exhibited before. A companion publication edited by Howard and the scholar and novelist Sadia Abbas includes conversations with Sikander and her peers, curators and teachers.

As she moved beyond Pakistan, Sikander has expanded her visual lexicon to render interior and exterior realities that encompass eras, geographies, and cultures. Images reflect such events as the political and military aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the African American diaspora. A rifle barrel and the shadow of a drone may coexist with a peacock and ribbons of calligraphy. Small in scale, her swirling, surreal images invite the viewer to take a slow, close look and discover their magnetism and wit.

While she studied at the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore from 1987 to 1991, she found a mentor in faculty member Bashir Ahmad, a master of manuscript illustration. Although the practice was then widely regarded as a traditional craft, Sikander recalls, “I perceived a frontier.”

Juxtaposing centuries-old manuscripts that would have been models for Sikander, the exhibition’s first section, “Studying in Lahore,” shows the artist’s early works exploring what she calls “female interiority.” In two images, her friend Mirrat returns the viewer’s gaze while posing in traditional Mughal and Sikh structures.

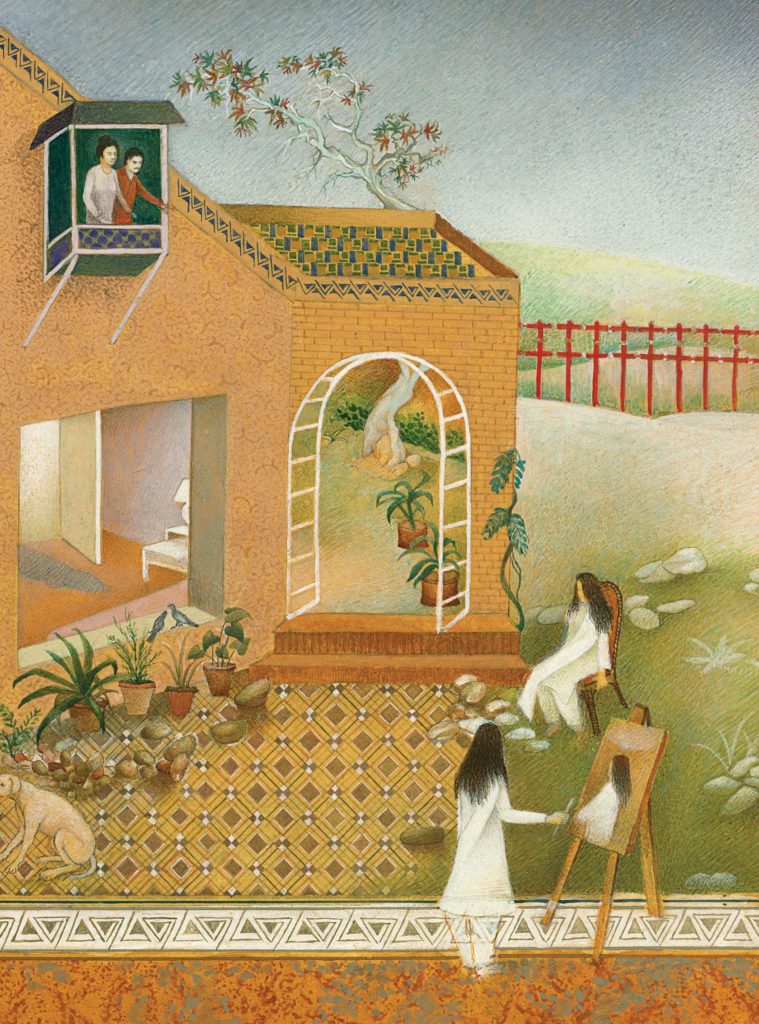

Shahzia Sikander “Mirrat I” Collection of the artist. © 2021 Shahzia Sikander. PHOTO: Courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London

Taking the tradition to a monumental scale is her five-panel senior thesis, “The Scroll” (1989–1990). An alternately translucent and solid female figure — an avatar of the artist — floats among the rooms in her family’s home, opening doors, peering out of windows, observing family members and painting a portrait of herself.

At Ahmad’s invitation, after earning her B.A. in 1991, Sikander stayed for two years as a teacher of manuscript painting, a major that became popular in the wake of her innovations.

But like the peripatetic figure in “The Scroll,” Sikander was on the move in her career and life.

From 1993 to 1995, Sikander attended RISD, where she earned a M.F.A. in painting and printmaking. While retaining the painstaking manuscript painting techniques, at RISD Sikander was challenged to produce 50 to 100 drawings a week, using large brushes and rolls of tracing paper. Tapping her subconscious, the rapid process yielded new, semi-abstract female avatars, and, says Sikander, “gave birth to my exploration of feminine power.”

In the section entitled “A Pleasing Dislocation in Providence,” Sikander’s drawings are shown with similar images by her late friend and faculty member Donnamaria Bruton.

The exhibition follows Sikander’s next two years as a Core Fellow in the Glassell School of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and her transition to New York, now her home. From the start, Sikander was in demand by collectors. Major solo and group exhibitions, as well as a 2006 MacArthur Fellowship, have widened Sikander’s visibility as an artist who transcends borders.

At the entrance and exit of the exhibition is a sampling of works by other women of color, including Simone Leigh, America’s representative at the 2022 Venice Biennale. Like Sikander’s works, Leigh’s sculpture, a female head in black terracotta atop a raffia skirt, emits power.