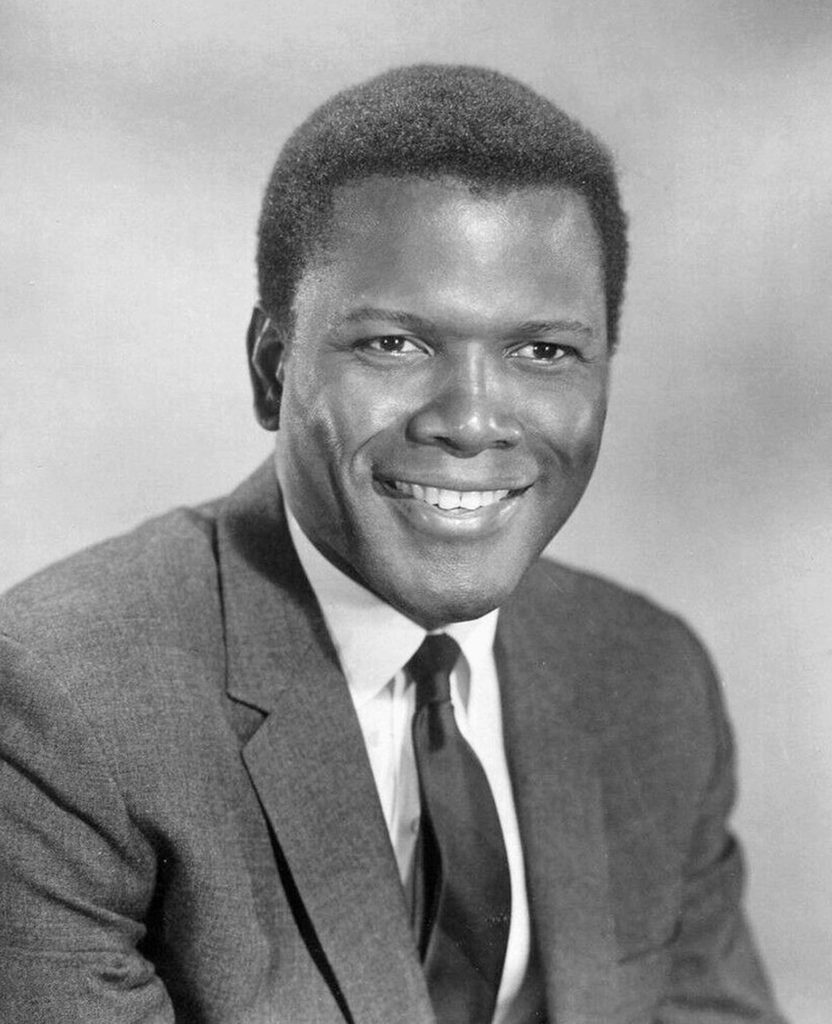

Sidney Poitier, the debonair matinee idol whose charm, steel and impossibly good looks lit up the silver screen and smashed through Hollywood’s image barriers, died Jan. 6 at age 94.

After a tentative start in the film industry in the early 1950s, the future Oscar-winner went on a 10-year tear of movie appearances that turned the stereotyped depiction of African Americans, especially Black men, on its head.

Starting with 1958’s “The Defiant Ones” and running through “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” and “In the Heat of the Night” in 1967, Poitier by turns saved a white man, kissed a white woman and slapped a white bigot.

At the dawn of the 20th century, W.E.B. Du Bois posed the “problem of the 20th century” as “the problem of the color line.” Time and again, Poitier found himself answering the riddles posed by that nearly unfathomable conundrum.

His appearance on studio lots in the early years of the civil rights movement gave Tinseltown moguls the perfect cinematic figure — calm, measured, controlled, dignified and with just a frisson of smoldering sexuality — to capitalize on the public’s rising interest in racial issues. Poitier’s ability to perfectly meet the moment provided the Bahamian-born actor with opportunities long denied to earlier generations of Black actors.

Stars like Paul Robeson, an immensely talented stage and screen thespian, singer and athlete, memorably picked up a shovel and brain-panned a white overseer in 1933’s “Emperor Jones,” but was hounded out of Hollywood and pursued by the FBI for his left-wing politics.

But Poitier, along with his close friend Harry Belafonte, stood in the front ranks of civil rights protests. His appearance at the 1963 March on Washington and other seminal events in the movement for equal rights arguably enhanced his appeal and added a thematic éclat to the sound of his open hand striking the face of an insulting plantation owner in “In the Heat of the Night.”

That, along with his emphatic declaration to the smarmy racist sheriff played by Rod Steiger, “They call me Mr. Tibbs!” drew cheers from Black movie-goers and dread from the antebellum set. What Poitier later called “the slap heard round the world” was a long way from Hattie McDaniel becoming the first Black winner of an Oscar for her role as Mammy in 1939’s plantation fantasy “Gone with the Wind.”

Poitier received an Academy Award nomination for his role as an escaped prisoner chained to Tony Curtis in “The Defiant Ones” and five years later won the best actor Oscar for his work in “Lilies of the Field” as an itinerant who helps a flock of German nuns build a church in the high desert of Arizona. In both movies, Poitier inverted conventional expectations by playing a Black savior.

But not everyone was taken with the novelty. James Baldwin notably expressed disappointment with the scene where the prison pair, finally freed of their chains, run to catch a moving train. Poitier athletically leaps aboard but Curtis, faltering, fails to reach his fellow inmate’s outstretched hand. Rather than escape alone, Poitier gallantly leaps off the boxcar, rolling in the grass to land up against his doe-eyed companion.

“When Sidney jumps off the train, the white liberal people downtown were much relieved and joyful,” wrote Baldwin. “But when Black people saw him jump off the train they yelled, ‘Get back on the train, you fool!’ The Black man jumps off the train in order to reassure people, to make them know they were not hated.”

By the time “In the Heat of the Night” was released nine years later, the Black Power movement was in full flower and Poitier could slap a bigot with equanimity. Jackie Robinson, to whom Poitier is often compared, swung a bat but never took a swing at a racist, like Poitier did, in full living color.

The reversal of conventional racial roles saw its logical completion at the end of the movie when, as Baldwin also suggested, Poitier received the verbal equivalent of an open-mouthed kiss from the weak-kneed, drawling Mississippi sheriff as Mr. Virgil Tibbs boarded a train to return home to Philadelphia.

Both comments by Baldwin, highlighted in Raoul Peck’s documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” captured the power and impact of Poitier on a nation looking for direction in an uncertain time.

In 1967 alone, Poitier’s resolute portrayal of distinctive, barrier-breaking characters produced the year’s three top-grossing films — “In the Heat of the Night,” “To Sir With Love,” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?”

Poitier was born in Miami in 1927 and grew up on Cat Island in the Bahamas, the youngest of nine children, helping his parents grow and sell tomatoes. He left the islands to join a brother in Florida at age 12 but soon ran away to New York and began an odyssey of odd jobs — unloading cargo on the waterfront, washing dishes and digging ditches — until he joined the army in 1943 and worked at a medical detachment on Long Island.

Feigning mental illness — his first professional acting job — he won a discharge from the service in 1945, and, with no acting experience, auditioned for a part in a play staged by the American Negro Theater in Harlem.

His heavy West Indian accent got him booted from the line-up of hopefuls. He then embarked on voice training and volunteered to work as an unpaid janitor in the troupe’s acting school.

His first break came when Harry Belafonte failed to appear for a rehearsal and Poitier won the part in an all-Black production of “Lysistrata” in 1946. A series of roles in film and television followed, with his first prominent turn coming in “The Blackboard Jungle” in 1956. Three years later, “The Defiant Ones” imprinted the Poitier stamp on the country’s cinematic landscape.

“The explanation for my career was that I was instrumental for those few filmmakers who had a social conscience,” Poitier later wrote in a comment cited by The New York Times.

After his banner year in 1967, Poitier began directing and producing and appearing in comedies and westerns, working with Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor.

In the 1990s, he made television appearances as Thurgood Marshall in “Separate but Equal” and as Nelson Mandela in “Mandela and de Klerk,” which won praise for conveying the steely dignity of the African National Congress leader. In an example of life imitating art, Mandela himself later said he modeled his public style on Poitier’s depiction of Virgil Tibbs in “In the Heat of the Night.”

Poitier, twice married and the father of six daughters, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Barack Obama in 2009 and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1974.

In 2002, he received a lifetime achievement Oscar during the same ceremony where Denzel Washington became just the second Black best actor award winner — 38 years after Poitier won his statute.

President Obama praised Poitier for opening the doors for a generation of actors and his ability to use “the power of movies to bring us closer together.”