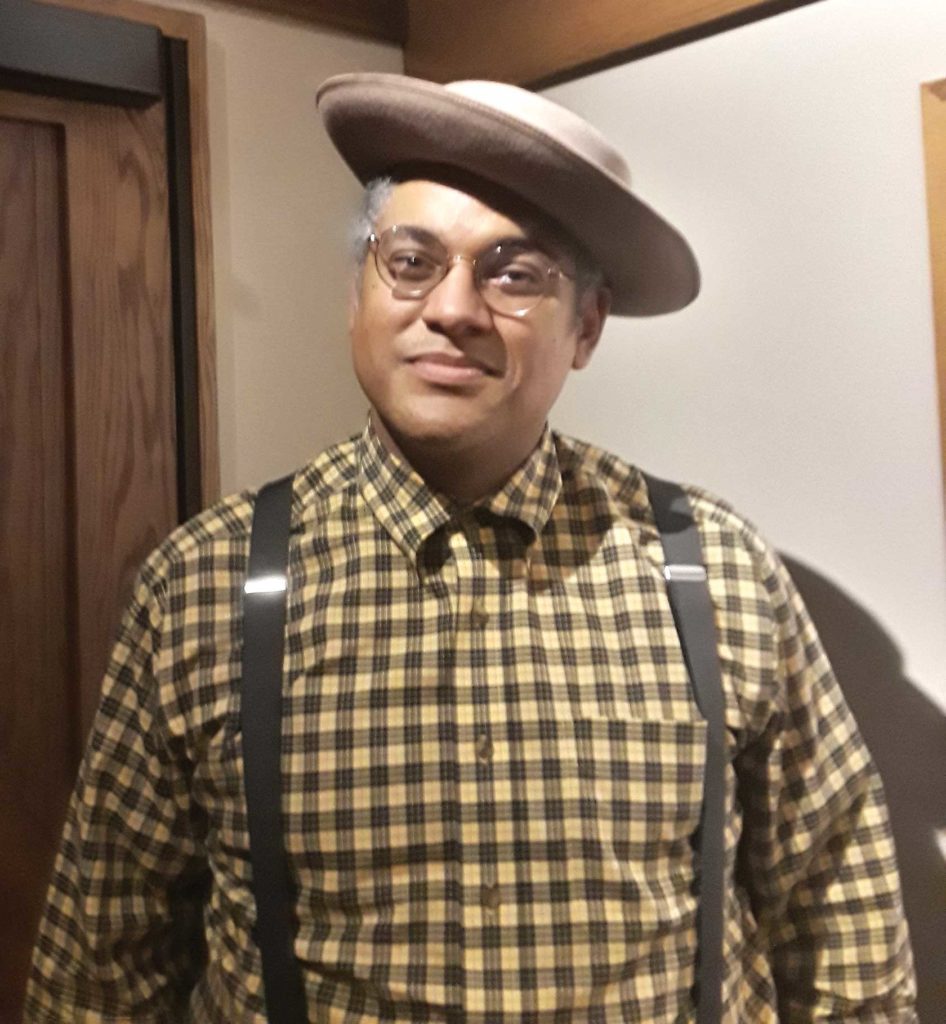

Dom Flemons is a modern-day “American songster” who pays homage to the obscured history of African American folk music while illuminating the memory of pioneers who left their mark on the genre’s austere roots.

Equally significant for this Grammy Award-winner and two-time Emmy nominee has been his commitment to the memory of folk music hero Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten, who is being inducted posthumously next month into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The “Early Influence Award’’ designee will share the honors with Harry Belafonte.

Flemons, 40, is a talented composer, singer, guitarist and banjo player in his own right. Born in Phoenix, Arizona, to Black and Mexican parentage, his secondary role as a historian and musicologist seem to loom as large as his prodigious musical abilities.

In the midst of a thriving musical career, not even last weekend’s appearance at the International Bluegrass Music Association Industry Awards in Nashville prevented him from carving out some time to talk about Cotten, a self-taught guitarist, banjo player and singer born in 1895 into a musical family near Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in a town later incorporated as Carrboro.

“If you see a picture of Elizabeth Cotten, everybody has a grandmother or great-grandmother reminiscent of her that was stoic, pleasant, and generous, and really appealing,’’ he says. “She wasn’t an Angela Davis. She wasn’t a revolutionary. She was low-key and very calm and collected, even though she knew the challenges for a Black woman in that time. I think with so much strife going on in the world, she didn’t allow that to be a part of her musical or stage presentation. It was like your great-grandmother picked up a guitar and just played.’’

Cotten did far more than just play, compose and sing. With her “Cotten picking” style adapted to a right-handed guitar set-up to suit her natural left hand, she helped revive the North Carolina Piedmont strum tradition from the turn of the 20th century to take a modern-day place during the Civil Rights era when Cotten, then in her 60s, finally began recording many of the songs she had written in her childhood.

Numbers like “Freight Train,” “Shake Sugaree,” “Willie” and “Going Down The Road Feeling Bad,” have been covered by folk and rock luminaries including Joan Baez, Taj Mahal, the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan and one of today’s shining stars — fellow North Carolinian Rhiannon Giddens.

Cotten’s precise articulation and jubilant interchange between the bass and melody strings bring a bouncy orchestral feel, accompanying a singing voice perfectly suited to tell the stories of the Carolina country people.

“She’s kind of like Lead Belly (Huddie William Ledbetter), because most method books are going to teach you “Freight Train” in the first two or three songs that you learn in the Carolina Piedmont style,” says Flemons. “She became such an essential part of that learning process for anyone learning finger-style guitar. Chet Atkins did it, so even country-and-western people acknowledge Elizabeth Cotten as an influence, whether it be from her recordings or that they may have heard it from somebody doing her style or her songs. At the end of the day, it all reaches back to that early North Carolina Piedmont strum band tradition.”

Deep roots

Flemons believes the music from the southern states of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky, was quintessential American music developed equally by Blacks and whites, with roots in Africa, the United Kingdom and Ireland, but he stresses that the banjo originated in Africa.

He laments, to the degree it has happened, Black disengagement from folk music. With the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a Black acoustic roots band he co-founded in 2005, he helped refocus eyes and ears on that lost history.

“I spent a lot of time trying to bridge the gap between traditional music of the 1920s and the recordings of the music of the 1930s,’40s, ’50s and on,” says Flemons. “I’ve really tried to show the people that there’s a relevance of Black music that precedes the commercial Black music that everyone is familiar with. Black culture was evolving in an urban setting in the 1960s, going into the Civil Rights era. At that time documentarians, primarily white college students and scholars, went down South, and they recorded a lot of these fringe styles of music. Some of these musicians were able to transcend into working musicians, touring and doing gigs and stuff like that, but others stayed in obscurity. I think that now there’s so much that can be done to bridge the gap between modernity and tradition within African American folk music. And that’s kind of where my music lies.”

Cotten, who was married in her teens, stopped playing music early on, working primarily as a domestic and raising a family. It wasn’t until her later years, after joining her daughter in Washington, D.C., and working for the renowned Seeger folk music family did she slowly regain her musical identity.

“She has this very interesting encounter in a department store,” Flemons says of a widely-circulated story that sounds more apocryphal than real. “She sees this little girl crying looking for her mother. She helps the girl find her mother. The little girl is Peggy Seeger. In the course of conversation, Elizabeth mentions to the mother, ‘Well, I do domestic work, if you need someone to work in your house.’ So she goes to work for them. And she began playing music in the house when no one was around. As the story goes, they heard her playing the guitar and she apologized. But they noticed she had a really beautiful style of playing, because she played her guitar upside down like Jimi Hendrix. They encouraged her to play more, and then Mike [Seeger] recorded her very first record in 1957. And that began Elizabeth’s career as a folk musician in the time of the folk revival.”

Flemons notes that Mike Seeger accompanied Cotten throughout her now-thriving career until she could no longer tour, leading up to her death in 1987.

Cotten’s delayed gratification, Flemons says, came to serve America at a time people were searching for clarity in their lives. In general, he thinks the integrity that underpins folk music lends tranquility to a fast-paced society.

“Her music was not necessarily made for the stage, nor for money,’’ he says. “There’s an aspect to the folk revival that’s really built on sincerity, being able to make music that is powerful but is also humble and is not built on a big commercial platform. Sometimes it’s to its detriment as well, because certain musicians are typecast into a spot where they need to be poor, and there’s an ebb and flow to that. But in Elizabeth Cotten’s day, it was such a new movement, especially in a young Baby Boomer generation wanting to find the heart of America, where right before the time of the Civil Rights movement, they were trying to find something real, tangible, something very rooted. So getting the chance to see someone like Elizabeth Cotten blew peoples’ minds.’’

Flemons says Appalachian folk music was an influential factor in the development of blues, jazz, rhythm & blues and soul music, and Cotten and her predecessors should be noted for their roles in music history.

“While she may have forgotten most of her music in the course of her lifetime, because there was no need for it or no place to play it, the folk revival allowed her to delve back deep in her mind, think of her childhood, and be able to pull back songs that are still a part of the documentation as well as the musical foundation of what was a part of North Carolina at the turn of the century,” he says. “If we didn’t have her, we’d be losing hundreds of songs. Just like any type of anthropology, it would just go away if someone hadn’t decided to put it down on paper and on recordings so it could be listened to and enjoyed. Now it’s been almost 100 years since she began to perform, so her music has withstood the test of time.”

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)