Opioid deaths on the rise in Mass.

Black residents account for largest increase in overdose death rates

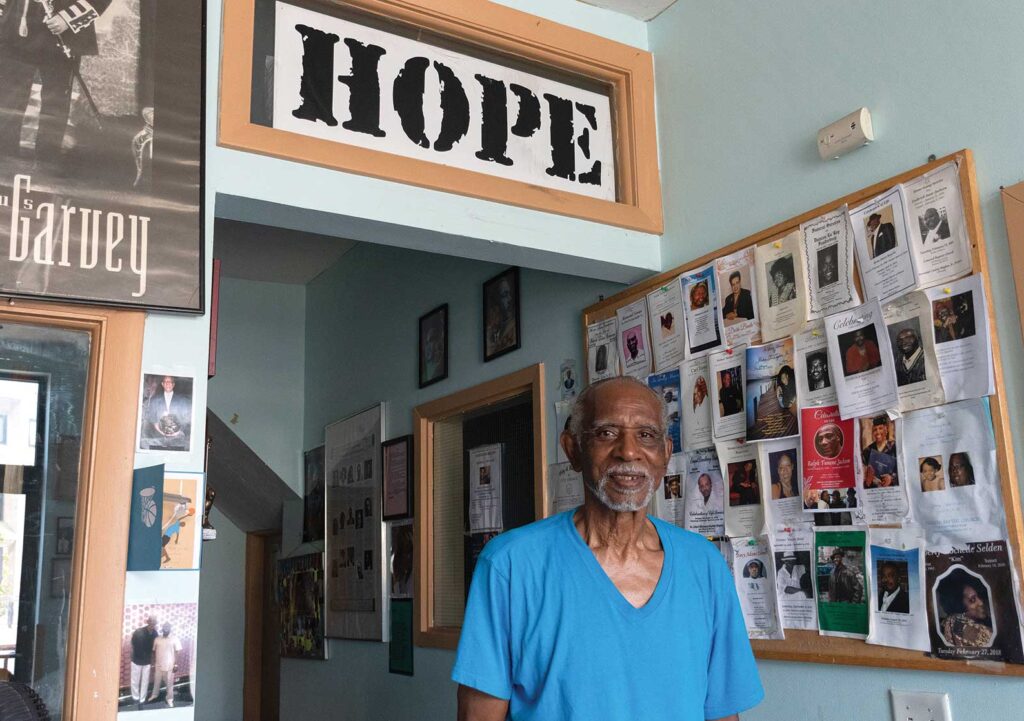

Greg Davis, who runs Metro Boston Alive in Roxbury, is no stranger to substance use disorders. Almost 38 years sober himself, he uses his experience to help guide others seeking sobriety.

From his substance abuse resource center near Nubian Station, Davis is prepared to help anybody who comes to his door. But he feels frustrated about the outsized disparity in populations of color struggling with opioid use.

“I was trained to help anybody that wants help. I don’t care what color you are, how old you are, what gender you profess to be or whatever — if you ask him for help, I’m going to do my best to help you,” Davis said. “However, emotionally it has this toll on me every now and then to see that this disparity still [is] going on.”

The disparity isn’t anecdotal. At the end of June, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) released data for opioid-related overdose deaths in 2022. The department found that the number of deaths in the state rose by 2.5% from 2021 to 2022, and that Black residents accounted for the largest increase in death rates.

According to the DPH data, the rate of Black Massachusetts residents who died from a confirmed opioid-related overdose rose by about 42%. Among Black men, it rose about 41%; among Black women, it rose more than 50%.

“The data is disturbing,” said Julie Burns, president and CEO of RIZE Massachusetts, a nonprofit focused on addressing the opioid crisis. “I mean, for too many years now, we’ve seen increases in populations that reflect, you know, different communities, but particularly the Black community. This should be yet another call to all of us to rethink our existing policies and investments and really start to laser-focus on interventions that will help people overcome addiction.”

Awareness of the disparity isn’t new. Burns said RIZE, which was founded in 2018, quickly determined that they needed to focus on inequalities in the addiction treatment system, particularly those affecting people of color.

Nancy Armstrong, senior director of programs and operations at Women’s Lunch Place in the Back Bay, said the issue ties into the broader disparities socially.

“You just see in this population, a group that has been systemically marginalized, that didn’t have any access to the positive aspects of the social determinants of health,” Armstrong said. “They had lousy educations, they had poor access to health care, where they live … You’ll see the repercussions of that, actually, almost happened since their birth.”

Burns’ organization has been taking steps to address part of the disparity. At the start of June, RIZE awarded $883,000 in grants to five nonprofit organizations statewide aimed at access and equity in opioid use disorder treatment, a grant initiative the organization began in 2021.

Those grants are funding programs like Davis’ Metro Boston Alive, in partnership with Massachusetts General Hospital’s Bridge Clinic.

Jasmine Irvin, who works with the Bridge Clinic, said the funds will go toward renovations at the Metro Boston Alive offices and developing culturally relevant education about substance use disorders.

The funds will also provide continued support of the clinic’s mobile set-up that provides services related to substance use disorders and hypertension, or high blood pressure.

“We like to meet people wherever they are at their drug use or their recovery journey,” Irvin said. “Some people may need medicated assisted treatment, which is fine. Some people just may want a recovery coach. Some people just coming just because they’re just trying to learn a little bit more.”

Another recipient of a RIZE anti-racism grant is the Women’s Lunch Place, which will be using the funding to hire a recovery navigator. Recovery navigators tend to be people who have successfully transitioned to sobriety, who can help guide and inspire others into treatment.

Other organizations, outside of those receiving RIZE grants, also have been taking steps to address the disparity.

When the only bridge to Long Island treatment programs closed in 2014, the Dimock Center, a community health center in Roxbury, responded by adding beds to its detox program. Now, in response to the data about disparities in opioid-related overdose deaths — first in 2020 during the start of the pandemic and continuing to this year — Dr. Charles Anderson, the center’s president and CEO, said the center is working to expand bed space in its other substance-abuse treatment programs.

“We’re currently adding more capacity to clinical stabilization, because quite honestly, we see ourselves in the same sort of unfortunate situation we were, where there’s still shortage of supply to meet an unfortunately increasing demand,” Anderson said.

As individuals and organizations across the city work to address the crisis and the racial disparity, they say they must do it in cooperation with one another.

Irvin said partnerships like hers between the Bridge Clinic and Metro Boston Alive allow bigger institutions to bring services into the communities that need them most.

“I think that people in the community who have been servicing their community, they’ve been doing this work for years,” Irvin said. “They’ve already built the trust of the community, and I think it’s up to the big institutions to support the community members and the partners who’ve already been doing the work.”

Armstrong, at Women’s Lunch Place, recalled an instance when the Victory Connector, a program based in Jamaica Plain, set up in the Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard area to provide services and day shelter to women and transgender individuals. At first, few people were showing up, but when Women’s Lunch Place started bringing meals to attract attention, more people started coming in.

“This is what happens in Boston all the time,” Armstrong said. “We’re just all working together to accomplish the same goal, and it’s why I think that we’re going to be successful.”