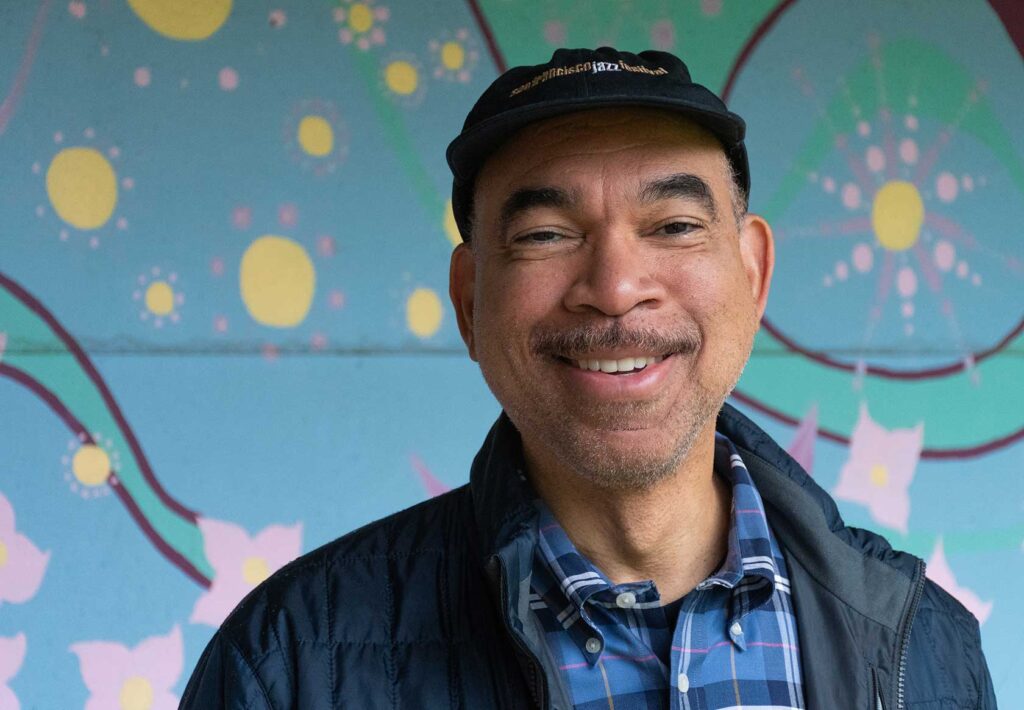

For Dr. Kirk Taylor, a long career in the pharmaceutical industry has been marked by a handful of consistent throughlines: a passion for medicine, loves for language and music, and a drive to work in diversity, equity and inclusion.

Like his childhood wish to be a doctor, his longstanding love for language that led to a bachelor’s degree in English literature and his start playing piano at seven, which led to studies at the Longy School of Music, the roots of Taylor’s work in DEI spaces — currently reflected in his involvement with groups like the Augustus A. White III Institute for Healthcare Equity — are long, stretching back to high school, where he served as president of its NAACP chapter.

Taylor, now chief medical officer at Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics, was recently named a standout executive by PharmaVoice, a leading industry publication. His current work at the New York-based company’s Burlington outpost focuses on injecting stem cells into the spine to bathe nerves in the brain and spinal cord, seeking a treatment for ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease, for which there currently is no cure.

In his career, Taylor has often found himself fielding questions about diversity equity and inclusion, even during his first job in the industry at Pfizer in the 1990s.

“I was immediately asked at Pfizer, ‘So hey, why is it that when we hire an ethnic person, why is it that they don’t stay?’” Taylor said. “Well, that was 1996. What year is it? It’s 2023 and we’re still trying to answer this question.”

The answer, from him, often came down to the third prong of DEI.

“You’re sitting around a table; there’s a diverse group of people. I’d say, ‘Fantastic, check that box’. Then there’s a dinner and lots of food, and you’re able to have the food: equity, ok great,” Taylor said. “But you look to your right, and the person’s not looking at you and sort of ignores you. You look to your left, and the person’s ignoring you. You’re not included. What a miserable experience that is. You have the diversity, you have the equity, but you’re not included in the conversation and then you want to leave.”

Companies can be well intentioned, Taylor said, but if coworkers don’t make the effort to make employees of color feel included, don’t listen to their opinions or follow through on their insights, they will leave.

Working to make his coworkers feel included is something he has done personally, not just advocated for, according to individuals who have worked with Taylor.

Dr. Richard Able, who currently serves as the vice president of global medical affairs at Praxis Precision Medicines, worked under Taylor at Sanofi, where Taylor served as vice president for North American Medical Affairs.

Able said that, when he worked under Taylor, he suggested ideas for new research. Instead of those ideas being dismissed or taken over by Taylor, he supported Able in tackling them himself.

Coworkers also described persistent investment in the diversity work he’s been doing for nearly three decades.

Taylor was a brand-new executive at EMD Serono, the American name of German pharmaceutical company Merck KGaA, when he was invited to attend the launch of the Leaders of Color Action Network, an employee resource group at the company.

Valerie Wright, who was one of the group’s founding members, said that the event was well attended by company executives who all showed up early in the day when there was attention on the new organization. But after public attention turned away, Wright said Taylor stayed when the rest of the executives left.

“We truly saw his engagement,” she said of Taylor. “We really saw his passion, his willingness to roll his sleeves up and engage with us, not from a senior leadership perspective, but from a participant perspective.”

That involvement eventually led to Taylor being tapped to be the resource group’s executive sponsor, its point of contact and advocate with higher-ups.

Not long after, the murder of George Floyd brought the group to the forefront. As soon as the next day, Taylor worked to organize a panel discussion to help staff of color express how they felt, Wright said.

The aftermath that summer of 2020 saw in-depth conversations working toward further understanding.

Taylor recalled nights, after his day job, where he would respond to emails from people working for EMD Serono and Merck KGaA across the world looking for information or support, even though the group was technically focused only on staff in the United States.

Some of those calls brought to his attention stories of people of color in other countries facing the same kinds of discrimination as in the United States. Others came from people looking for guidance on how to be antiracist.

“At that point, you have to ask yourself, ‘Do I want to miss the opportunity to help someone on that journey?’ Or do I want to say, ‘No, I’m tired. No, it’s not my responsibility,’” Taylor said. “It’s a personal choice.”

Early in his career, Taylor’s made his work in DEI a practical matter.

As a stipulation, he added to his contract with Pfizer. He saw patients once a week at a neurology clinic in the South Bronx, where that work encouraging diversity became a hands-on endeavor. When adults would come into the office with kids, he’d take a moment to ask what they wanted to do when they grew up.

He’d often hear “police officer” or “gang leader” — the people that those kids saw who had power, Taylor said. He’d try to offer them a new option with one question: Had they ever thought about being a doctor?

“At that moment, it was planting a seed that it was possible,” Taylor said. “The first question is, ‘Did you ever think of it?’ … If this is for you, did anyone ever say you could do it?”

Now, as Taylor, 60, looks toward the future, a pending but not imminent “phase three” of his life is on the horizon — one where he plans to take a step back from work in the industry to focus instead on serving on boards and working on writing to share what he’s learned.

Already, he has served on the board of a chamber music group as well as the Augustus A. White Institute of Health Equity.

“There are articles to write, there are maybe stories to tell that would help others. I’m a Christian guy, I believe in the Trinity, and I think we have the practice of testimonials. Through testimony you help other people because they can learn from your story, and I think I have stories to tell,” Taylor said. “I think all of us have a responsibility, after we get out of a career, to say, ‘What did I get out of this and what can I share with others?’”