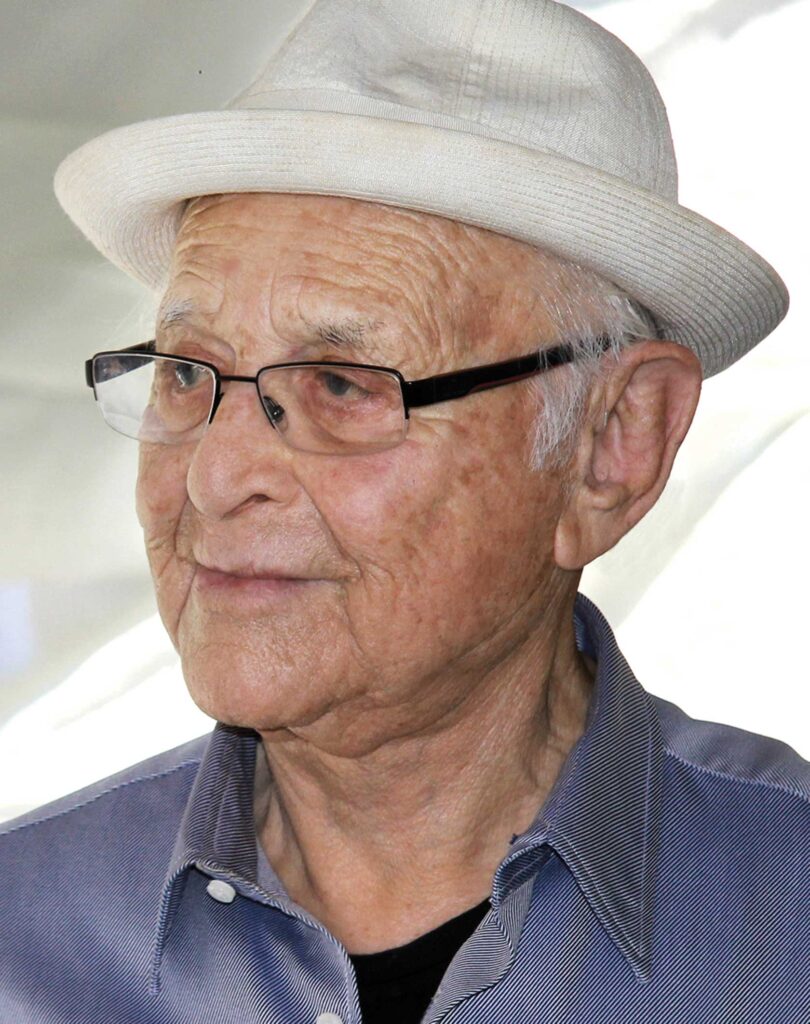

Most people won’t live to be 80 years old, which makes Norman Lear’s eight-decade career even more poignant. The television icon passed away at age 101 on Dec. 6 at his home in Los Angeles.

Norman Milton Lear was born on July 27, 1922, in New Haven, Connecticut, to Jeanette and Hyman “Herman” Lear, a traveling salesman. Both parents were of Russian-Jewish descent. His younger sister, Claire Lear Brown, preceded him in death in 2015.

Lear’s life changed when he was 9 and living with his family in Chelsea, Massachusetts. His father went to prison for selling fake bonds. Norman became the man of the house, and realized there is a lot of humor even in painful situations. The character of Archie Bunker in “All in the Family” was partly inspired by his father, and his mother inspired the character of Edith Bunker.

“All in the Family” came to American television on January 12, 1971, to disappointing ratings, but it took home several Emmy Awards that year, including Outstanding Comedy Series. The show did very well in summer reruns and became the top-rated TV show for the next five years. Lear’s second big TV sitcom, “Sanford and Son,” was based on a British sitcom, “Steptoe and Son,” about a west London junk dealer and his son. Lear changed the setting to the Watts section of Los Angeles and the characters to African Americans, and the NBC show “Sanford and Son” was an instant hit. Numerous hit shows followed, including “Maude,” “The Jeffersons” (both spin-offs of “All in the Family”), “One Day at a Time” and “Good Times” (an offshoot of “Maude”).

Lear’s shows touched on hot-button issues such as civil rights activism, alcoholism and abortion, and went far beyond one-dimensional portrayals of Black characters. His shows depicted television’s first two-parent Black family, and an upwardly mobile one. It was groundbreaking, but indeed challenging. Some characters in his programs were the source of flare-ups, particularly when some Black cast members complained about stereotypical portrayals, which are still debated today. Two Black writers, Eric Monte and Mike Evans, are credited with creating “Good Times,” but have struggled to receive recognition for their contributions. Monte also argued that Lear stole his idea for “The Jeffersons.” He received a $1 million settlement and said he was eventually blacklisted from Hollywood. Yet despite those tensions, it’s hard to find anyone in the medium of television who is held in such high regard, including by many Black writers and showrunners creating and running today’s shows.

Kenya Barris, the creator of “Black-ish,” told the New York Times, “It’s like asking someone who played basketball if Michael Jordan influenced them. He changed the way contemporary storytelling was told in the genre that I was doing it in.” Barris said that Lear was an early champion of “Black-ish,” and even visited its writers’ room in 2016. “It’s about as impactful in modern media as a legacy could be,” Barris said of Lear’s body of work.

Lear’s interest in real human stories was also shaped by his time in the military, and he has often credited the Tuskegee Airmen “Red Tails” for saving his life on several occasions. After leaving Emerson College in Boston before graduating, Lear enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces in September, 1942. He served in the Mediterranean theater as a radio operator and gunner on Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. He flew 52 combat missions and received the Air Medal with four oak-leaf clusters. The all-Black “Red Tails” squadron escorted his bomber plane in and out of enemy territory.

A few years ago, Lear said in an interview, “There used to be this great act, the Nicholas brothers — they did giant leaps off high stage pieces to the floor, landing in that split thing. They were amazing. Amazing. And the Tuskegee guys were the Nicholas Brothers in the air. They had that same spirit. I don’t know on how many occasions I could see the faces of the airmen; they were so close. The way they came in and peeled off, they just flew like the Nicholas Brothers danced.”

Lear was so involved in politics that he purchased a rare copy of the Declaration of Independence and took it on a road trip around the country. In 1974, he was one of the founders of the Caucus for Producers, Writers and Directors.

Norman Lear never really stopped working. He has received too many awards to mention in this remembrance. He spent his 100th birthday on Martha’s Vineyard and had his usual weekly dinner with his friends Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks just before he passed. Six children and his wife, Lyn, survive him. As Lear said recently about his life, “It’s been the greatest ride of all rides.” Yes, it has! R.I.P Norman Lear.