As a young girl growing up in the west side of Chicago, Chaz Ebert was most notably two things: a voracious reader and a precocious entrepreneur. Both her mother, who worked at a publishing company at the time, and one of her sisters, who shaped Ebert’s reading tastes, were bookworms, and Ebert followed in their stead.

She recalled tearing through the Nancy Drew series and tucking into stories about influential women of the past, the likes of Sojourner Truth and Eleanor Roosevelt.

When she wasn’t getting lost in mysteries or histories, the young Ebert was starting businesses. While she dabbled in setting up the typical lemonade stand, the real money was in a bank she created at 8 or 9 years old, using deposits to buy candy, which she would sell at a profit, returning her clients’ money to them with interest.

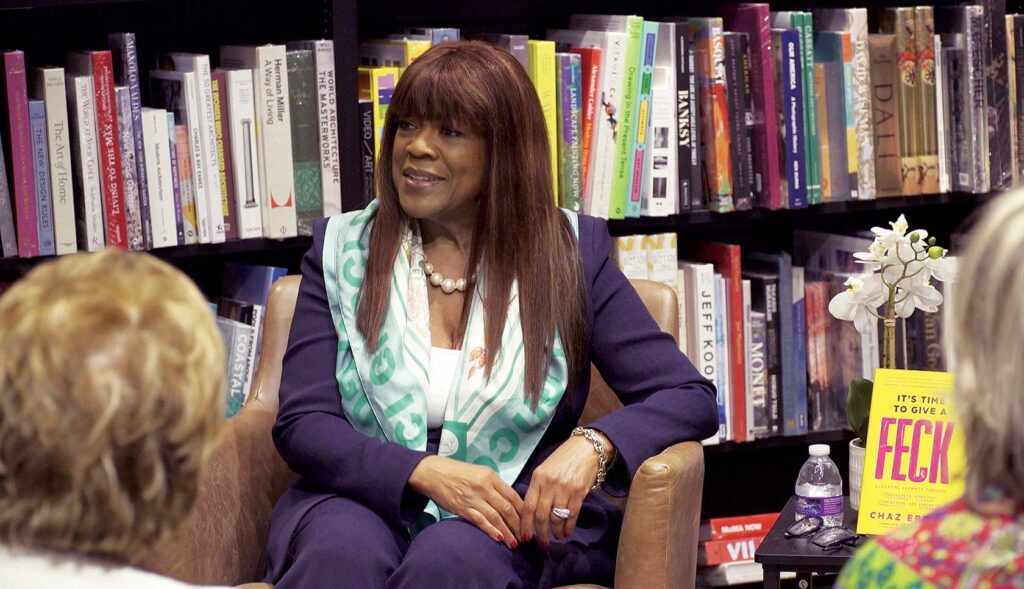

Decades later, the bibliophilic and entrepreneurial interests of her childhood collided as Ebert added author to her long list of career titles, which include legal adviser, attorney, movie producer and CEO of Ebert Digital. Last week, her book, “It’s Time to Give a FECK: Elevating Humanity through Forgiveness, Empathy, Compassion and Kindness,” hit shelves nationwide, and she stopped by Hummingbird Books in Chestnut Hill to promote it.

Ebert doesn’t quite remember exactly when she first started writing the book, but she finished a version of it before 2020. When the pandemic began, she realized that the world had changed in ways that weren’t reflected in her book. So, she began a rewrite that was more of “a guide of how we could reconnect with each other,” she said. As the pandemic wound down, the book seemed too “doom and gloom,” so she course-corrected once again “to make it more green.”

The book’s title is simply an acronym for its four guiding principles of forgiveness, empathy, compassion, and kindness. But, Ebert admitted, it’s also certainly cheeky.

“It is tricky because as I’m doing the book tour, I noticed when people say the title, they are very careful to articulate. ‘I said F-E-C-K. FECK,’” she said in an interview, imitating some of the statements she’s heard. “And I know if I go to the UK, that’s gonna be a whole [other] thing.”

Ebert and the publisher discussed alternative titles and even surveyed about 200 people. In the end, the current title was a winner.

Ebert is best known as the wife and widow of renowned film critic Roger Ebert. She’s unsure if people immediately associate her with her late husband before knowing who she is, but even if they did, she said, it wouldn’t bother her. In fact, Roger Ebert is front and center in the book.

“The “e” in the word FECK…can be empathy or Ebert,” she said, noting her late husband’s view of movies as being an “empathy machine” that allows spectators to walk in other people’s shoes. She even dedicated the book to him, “whose capacity for empathy knew no bounds.”

Where Roger Ebert championed empathy, in her talks, Ebert often spoke of compassion and kindness, two of the book’s other principles, which she said are the result of empathy.

She realized that once you empathized with someone, “it helped you to develop a compassion for that person,” she said. “And if they had a struggle or challenge, your compassion made you want to help do something about it to alleviate their suffering, and that’s where kindness came in.”

The fourth principle, forgiveness, became apparent to her in an encounter with the late South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, detailed near the beginning of the book. During the meeting, in the vault of the Abraham Lincoln Library in Springfield, Illinois, the subject of South Africa’s fight against apartheid arose. Ebert asked Tutu why Nelson Mandela had not sought revenge against the perpetrators. “Without forgiveness there is nothing,” he told her.

“Forgiveness lays the foundation for us to be more empathetic, compassionate, and kind,” Ebert writes. “Empathy allows us to deeply understand and relate to others. Compassion leads us to want to help alleviate the suffering and lift the spirits of others, so they can fulfill their destinies. Kindness, then, becomes about the simple acts that spur forgiveness, empathy, and compassion into action.”

The building blocks of Ebert’s book are anecdotes in which individuals or groups displayed forgiveness, empathy, compassion and kindness in ways that astounded her. She writes about families who forgave mass shooters, the activism of NFL star Colin Kaepernick, the resilience of Mamie Till after her son Emmett’s lynching in Mississippi in 1955, and more. Ebert had a plethora of such anecdotes to choose from, but “those stories chose themselves for the book.”

During her childhood as the eighth of nine children in a house bubbling with laughter, Ebert witnessed the FECK principles at play, too, she said. Her mother was the kind of person who “brought the sunshine with her” when she walked into a room. And her father, although quiet and reserved, showed his love by taking care of his family.

“It’s only later in life that I realize maybe some of the things that I was given through my relationship with my family were things that were filling me up to do some of the work that I’m doing today,” she said.

She engages in philanthropy work through the likes of the Roger and Chaz Ebert Foundation, which awards grants to women, families and children in the arts, and the Ebert Fellowship, which supports emerging film professionals through grants and mentoring.

Many of the anecdotes in Ebert’s book are drawn from moments in other people’s lives, but she sometimes turns inwards. In one chapter, she writes about the moment she — the unmarried “good girl” and the first in her family to attend a four-year higher education institution — discovered she was pregnant in her first year of college.

Months into her pregnancy, she called her parents in tears, worried she had disappointed them and expecting to be chided. Instead, she was met with understanding, as her parents told her they loved her.

“It meant everything to know that I was still so valued in the family — that I was so loved. And when my son was born, he was so loved,” Ebert said, adding that her parents took care of her son while she was in school.

When her parents displayed compassion during Ebert’s pregnancy, it wasn’t the first time they had shown up for her in this way. One of the first and more memorable times, she recalled, happened when she was four years old. There had been a fire at Ebert’s family home and her dress caught on fire. She watched as her dad tore the dress off her body with his bare hands, despite the threat of burns.

“I was like, ‘Would I put my hands in a fire to tear somebody’s clothes off…if my hands were gonna get burned? I don’t know,’” she said. “But I remember admiring my father even while I’m terrified. And I remember how everyone in the hospital was so kind to me.”

Ultimately, “It’s Time to Give a FECK,” is a book about love, Ebert writes, and underpinning it is a message of community. It’s important for people to know that they have someone in their corner, she said, because not everyone does. And community can manifest itself on the most fundamental of levels.

“I’ve learned that giving a FECK has to be about fulfilling the basics first,” Ebert writes in the book. “That means supporting local families with food to eat, a roof over their heads, streets that are safe to be on at any time of day or night, neighbors who watch out for one another, and an end to gun violence and deaths.”