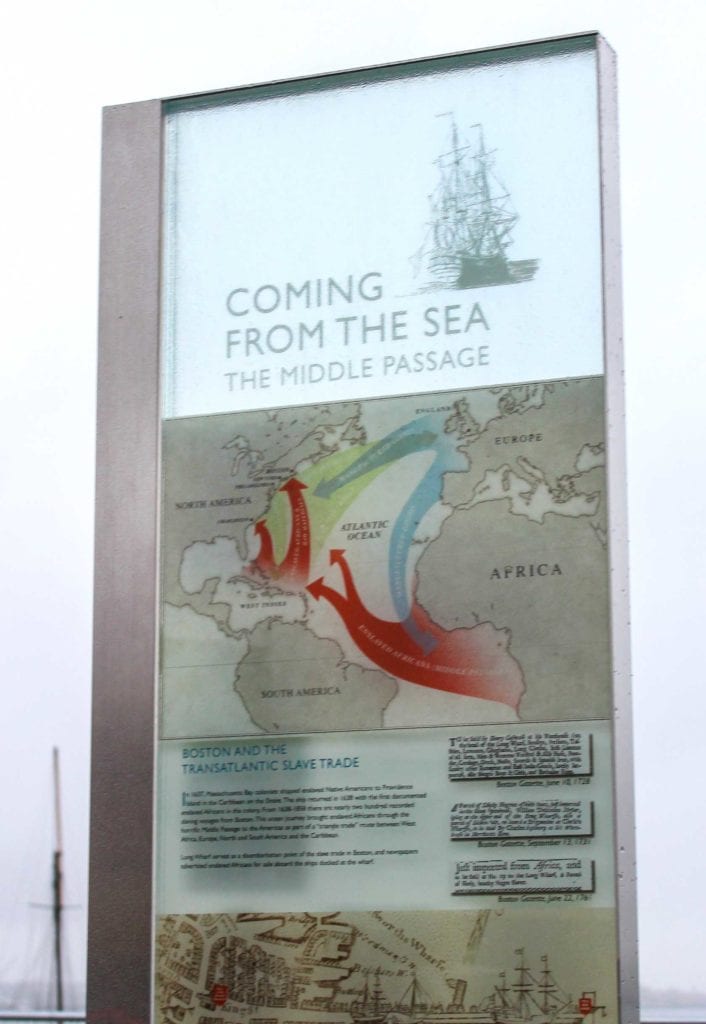

Middle Passage memorial marker acknowledges Boston’s history of slavery

In early October, a memorial marker was installed at the end of Boston’s Long Wharf to acknowledge Boston’s history of slavery and to honor the Africans who died in and those who survived the transatlantic voyage known as the Middle Passage.

This commemoration has been underway since 2015, when UNESCO named 31 Middle Passage sites around the country. These Sites of Memory included the Boston waterfront. Since then, the National Parks of Boston, Museum of African American History, Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project, Boston Art Commission, and former State Rep. Byron Rushing have been at work researching and designing this port marker.

“The Middle Passage Marker signifies the evolution of a free Black community that begins with the arrival of the first documented enslaved Africans on the shores of Boston in 1638,” says Museum of African American History President Leon Wilson. “It demonstrates the challenges to people, who by necessity, created their own to establish their spaces to accomplish freedom.”

The marker sits at the end of the wharf, overlooking the ocean. On it, visitors can find information about the Middle Passage journey and Boston’s complicity in the slave trade. It also notes some of the important African American figures and sites in Boston history. Among them are Phillis Wheatley, the first African American author of a published book of poetry; Prince Hall, an early abolitionist and champion of the back-to-Africa movement, and Paul Cuffee, a whaler and ship captain who became one of the wealthiest African Americans of the late 18th century.

“The Museum’s African American Meeting House, built in 1806, is one of the those gathering spaces featured on the marker,” says Wilson. “We are proud to acknowledge its completion to honor our ancestors, some lost in the journey across the Atlantic Ocean, and the celebration of those who survived. We are delighted to join with other national ports, the City of Boston, NPS and our collaborative partners in this moment.”

The marker serves as a memorial to the millions of African people who were transported against their will between 1619 and 1865 and died on these ships, as well as those that survived and were sold into bondage and the Native Americans in the Boston area that were then sold into slavery in the Caribbean.

Though the project has been years in the making, the port marker installation is particularly timely as Boston turns inward, reflecting on which histories and monuments it should be uplifting.