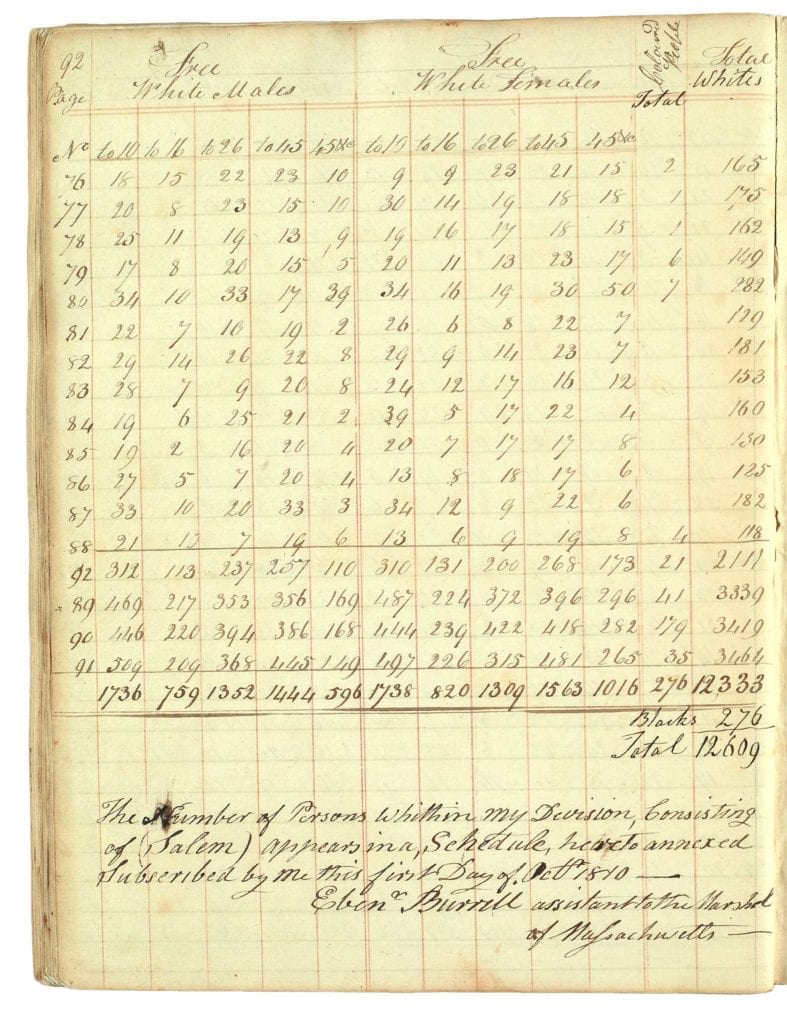

The Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library discovered at the end of April that the power of social media isn’t limited to marketing and advertising. While preparing an Instagram post for the PEMLibrary account, Meaghan Wright and Hannah Swan discovered an 1810 census of Salem, Massachusetts in a selection of un-catalogued records. That census has developed into a treasure trove of information about the historical Black population of the city.

“It’s significant, because we’ve been led to believe that this is the only copy of the 1810 census for Salem, Massachusetts,” says Dan Lipcan, Ann C. Pingree director of the Phillips Library. “It was a really early census, and 1810 was the height of Salem’s prominence as a shipping and trading city.”

In the document, the population is categorized as either “Free white males,” “Free white females” or “Colored people.” This catchall categorization, which doesn’t have a further breakdown for age and gender like the white categories do, illustrates the bias against people of color at that time. Although slavery had been abolished in Massachusetts in 1783, the state supreme court had not yet ruled that enslaved people brought into the state were free.

But we do get several crucial pieces of information from this document. The first is names of the Black heads of households. The second is a sense of where Black families were living. Because census information was compiled by a door-to-door questionnaire, researchers can get a sense of which neighborhoods were predominantly Black at the time and which individuals specifically were living there.

The names of Black heads of households recorded in the census are: John Chadwick, Cato Foster, Jenna Jacobs, John Taylor, Primus Jacobs, Andrew Thomson, Titus Anthony, John Phillip, Jenna Wilson, Flora Portsmouth, Sara James, Sipeo Freeman, Briston Treck, Obed Dickinson and John Remond.

“I think it’s really exciting, because historically our in our collections there’s been a real focus on the white settler community, and we think it’s time to turn our attention to Black communities and Indigenous communities that have lived in this region,” says Lipcan.

The census is so significant, in fact, that the National Archives reached out to PEMLibrary about it. Because it’s a national census document, and therefore property of the Archives, it has been placed in their care. The newly discovered information bridges a critical gap in the federal census information about Salem, which at the time was a significant shipping capital.

This discovery is particularly valuable for putting the puzzles of Black family history together. Researchers can now find names, dates and places for Black residents of Salem in 1810. In genealogy, any one of these items can light up a family tree.

The 1810 census is viewable online through the Phillips Library and the National Archives.