It was a moment that, to many, may have looked like defeat. William Celester was demoted from night commander — one of the highest posts ever occupied by a Black cop in Boston — back to his post as deputy superintendent at Roxbury’s Area B-2 station.

Boston police officer Larry Ellison, a former president of the Massachusetts Association of Minority Law Enforcement Officers (MAMLEO), walked into Celester’s office with a three-star stripe to replace the four-star one that now had to come off.

“I thought I was going to visit a broken, defeated man,” Ellison recalled. “But as I took the four stars off his shoulder and put the three stars on, he had this bright smile on his face. He said, ‘I’m back home.’”

Celester, who died of heart failure early Monday morning at age 78, grew up in the Madison Park section of Roxbury. As a teenager, he ran with a gang called the Marseille Dukes, at times running from the officers in whose footsteps he would later follow.

In 1965, the Bay State Banner established a recruitment program to diversify the Boston Police Department, which at the time had just 30 Black officers out of a total of more than 2,800. Celester, who was working as a sandblaster at the Charlestown Navy Yard, was one of the first recruits.

During his early years on the force, Celester said, he and other Black officers weren’t treated as equals.

“The general attitude was, you were on the same job as the white officers, but you really weren’t one of them,” he said in a 2017 interview with the Banner. “It wasn’t hostile, but you weren’t invited to go out for drinks or to parties with the white officers. Their attitude was, ‘You guys should know your place.’”

But after six Blacks and two Puerto Ricans filed a lawsuit arguing that Black and Latino applicants were routinely passed over for Civil Service jobs, a 1972 ruling in favor of the plaintiffs led to an increase in officers of color and mandated that the department promote Black and Latino officers.

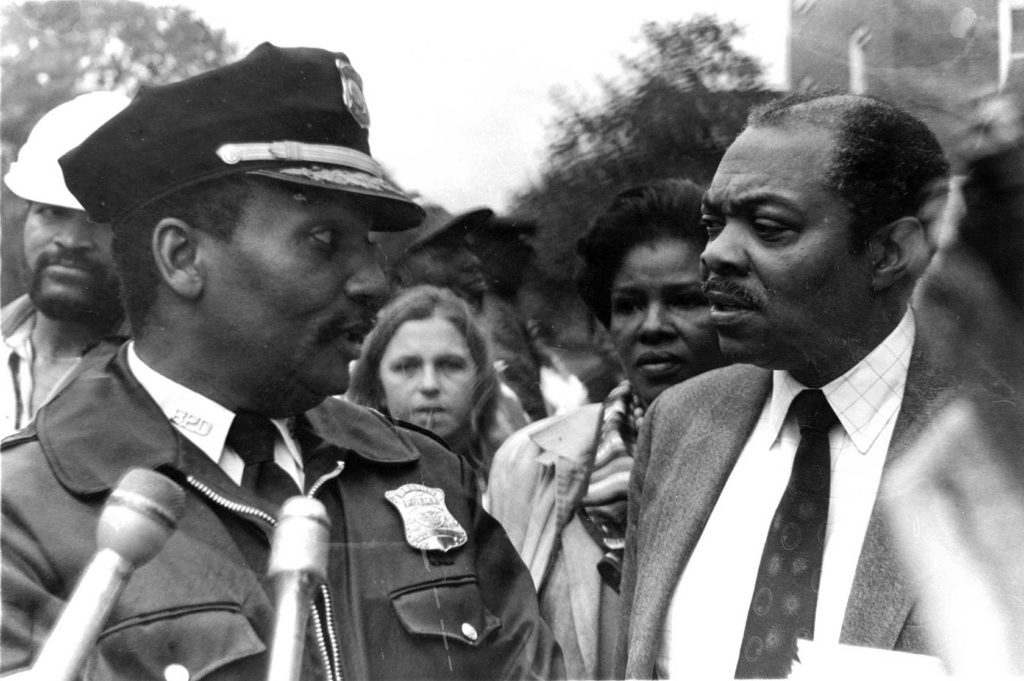

By 1979, Celester was the head of the newly formed MAMLEO and there were 200 Black officers on the force. When Mayor Raymond Flynn began his first term in 1984 and appointed Francis “Mickey” Roache as police superintendent, Celester was tapped to head Area B.

As a deputy superintendent, Celester had the power to promote Black and Latino patrolmen to the rank of detective, which officers who served at the time said happened frequently.

More importantly, Ellison said, Celester looked out for the Black and Latino officers who were still operating in a department that was hostile to people of color.

“When it came to advocacy and putting checks and balances on the system, Celester and the others who formed MAMLEO were pioneers,” Ellison said.

In addition to appointing detectives, Celester was also able to make temporary appointments to the rank of sergeant and lieutenant at a time when few Black officers held such ranks.

With his own ascension to night commander, he seemed poised for advancement. But, Ellison said, Celester was never one to go along to get along. In the end, he said, Celester’s unwillingness to overlook the unfair treatment regularly doled out to Black cops may have cost him the stars he earned with his appointment as night commander.

In any event, the return of the well-respected commander to the precincts at the heart of the city’s Black community was welcomed.

“His demotion was the community’s gain,” Ellison said.

In the end, Celester understood that he had gone as far as he could in Boston. In 1991, he took a job as commissioner in the Newark, New Jersey police department.

But in a 1996 public corruption case, he was convicted of taking money from an account used to pay drug informers for personal use. Some saw Celester’s conviction as retribution for his refusal to cooperate with a longstanding public corruption investigation directed at then-mayor Sharpe James.

Celester was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison and ordered to pay $8,000 in restitution.

“This account had been used that way for the last 20 years, and Bill Celester was singled out,” he told the court at sentencing.

After completing his sentence, Celester returned to Boston. While he never returned to public service, he remained an elder statesman in the Black law enforcement community.

Former District 4 City Councilor Charles Yancey recalled Celester as a public servant committed to his community.

“Billy Celester had a very difficult job in the Boston Police Department, but he handled it well,” he said. “He did it with dedication and compassion, particularly for our community. While I mourn his loss, I can’t help but smile at the efforts he made to improve the quality of life for people of color in the city of Boston and his efforts to make sure that the police department respected the Black community.”

Ellison said officers of color will remember Celester as a trailblazer who fought hard for the rights of Black and Latino officers.

“I learned from him what it was like to be a Black man and a police officer,” he said. “And that those two things don’t have to be mutually exclusive.”

Funeral arrangements are being handled by the Floyd Williams Funeral Home. The wake, viewing and service are scheduled for Sunday, March 6 at Morningstar Baptist Church.