Introducing The Banner’s Encyclopedia Climatica: What is geothermal energy and how does it work?

The Bay State Banner wants to hear your questions about the climate and environment. This article was produced as part of a new project called Encyclopedia Climatica, in response to a reader-submitted question. Do you have a question about climate or environment? Submit it to us at Encyclopedia Climatica or email to ableichfeld@baystatebanner.com.

A reader asks: “Can you explain how geothermal energy works and how it can be applied to housing? Is it ‘clean’ energy?”

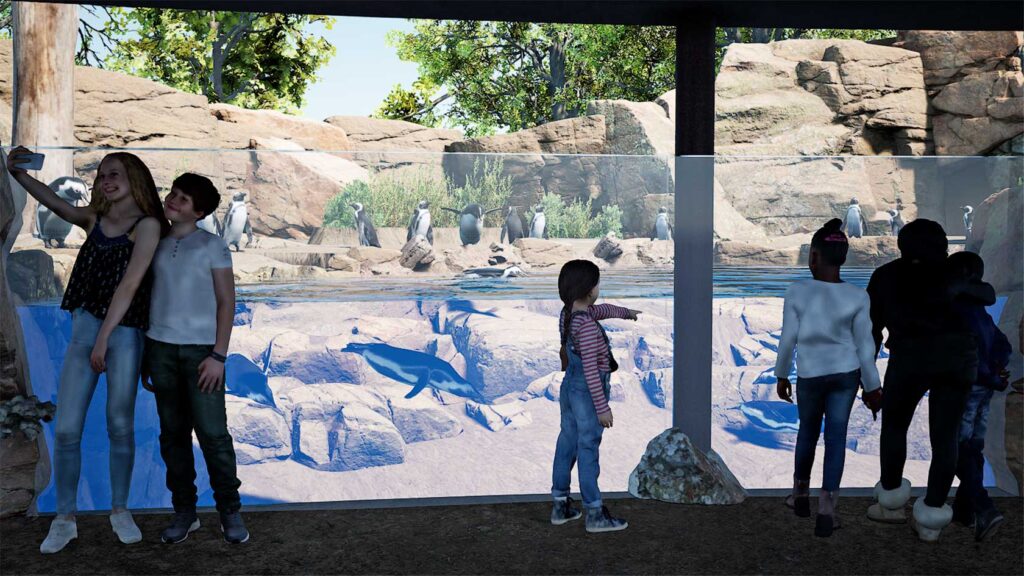

A rookery of new residents will be moving into Franklin Park Zoo next year. When that colony of African penguins arrives next spring, the exhibit that will house the temperate birds will be heated and cooled by the heat of the earth.

The system will use 20 boreholes — vertical pipes, installed 600 feet into the ground — to pump a heat-transferring liquid through a geothermal system to regulate the temperature of the water and the air inside the new building.

It doesn’t come cheap — the system costs an estimated $800,000 to $1 million more than a traditional setup, said John Linehan, president and CEO of Zoo New England.

But it will operate more efficiently, meaning a reduction in carbon emissions, a priority for Zoo New England, which runs Franklin Park Zoo.

“Being a conservation organization means setting good examples and using technology where we can, to reduce our carbon footprint,” Linehan said.

Geothermal systems aren’t just for the birds. Increasingly, across the region, geothermal is being used to heat and cool homes, a solution that advocates, officials and researchers celebrate as an important step toward decarbonizing Massachusetts.

“It’s a sustainable, reliable resource that we have, and we have it beneath our feet,” said Melissa Lavinson, executive director of the state’s Office of Energy Transformation.

Broadly, with geothermal, there are different ways the earth’s heat can be used, including for heating and cooling and for generating electricity.

Geothermal for heating and cooling

In New England, the most prominent — and currently only — use of geothermal is for heating and cooling buildings, like the pending penguin enclosure.

The systems rely on the constant temperatures found at shallow underground depths. There, temperatures tend to hover at a consistent level, locally about 55 degrees, which allows geothermal heat pumps to pull heat up into buildings in cold weather or tuck heat underground when it gets hot out.

In hot weather, those systems pump a “geothermal fluid” — generally a refrigerant like in an air conditioner — to pick up heat from a hot room. The fluid is then carried underground to let the heat dissipate. In cold weather, the reverse occurs. In both cases the physics of compressing and expanding gases is used to amplify the transfer.

“All you’re doing is using that constant temperature underground to act as either a heat source or a heat sink, meaning it’ll either take the heat out of a cooling fluid or add heat to that fluid,” said Emily Ryan, a professor of mechanical engineering at Boston University and an associate director at the school’s Institute for Global Sustainability.

Unlike geothermal for power generation, heat pumps are an appliance, not a source of energy.

“If people start to hear the publicity around this networked geothermal, and they’re like, ‘Great, we’re going to get geothermal energy,’ but you’re not,” Ryan said. “You still need electricity from our grid to power these systems.”

For supporters, the benefits of a geothermal system are plentiful. The systems tend to be more efficient than traditional HVAC systems.

“From a decarbonization perspective, it can actually help reduce peak electric demand,” Lavinson said. Geothermal heating and cooling systems are up to 65% more efficient than traditional HVAC systems, according to the U.S. Department of Energy

And in a region like New England, with old housing stock built for cooler temperatures, it can add a cooling system to buildings that didn’t previously have air conditioning.

Supporters also see a lot of potential in the ability to make the transition. Much of the labor needed for laying out the pipes needed to transmit heat underground is carry-over from gas systems.

“Digging, putting in pipe, connecting pipe to homes and businesses, that’s stuff that we do every day,” said Liam Needham, Eversource’s director of customer thermal solutions.

Already, there’s been proof-of-concept of that transition at an Eversource geothermal project in Framingham, said Zeyneb Magavi, executive director at the Home Energy Efficiency Team, or HEET, a Boston-based nonprofit focused on the thermal energy transition.

“The gas pipe installer workforce, they literally went from installing gas pipe one week to installing [geothermal] pipe the next, with a couple hours of training,” said Magavi (HEET pitched the project to utilities and has been involved in the process).

The needed workforce doesn’t wholly exist yet. A key element of geothermal HVAC systems are the boreholes — those vertical pipes, often a few hundred feet deep, that reach constant temperatures. While some companies exist to drill those boreholes, that segment of the workforce needs to be expanded.

“Drilling is obviously something that’s done for industry, for oil and gas extraction, but I don’t know if we necessarily have the workforce in place if everybody decided they wanted geothermal,” Ryan said.

And the cost of installing the systems remains prohibitive. For a single-family home, Magavi said that installation of a geothermal heat pump can cost between $20,000 and $60,000. According to Angi’s List, installation of a new boiler averages about $6,000.

“It’s kind of like if you had to install your gas boiler and pay for all your gas up front,” Magavi said.

One solution is linking a collection of homes or businesses to the same heating system, called networked geothermal.

That bigger system, likely owned and operated by a utility, saves individual customers the costs of installing geothermal heat pumps while bringing the same benefits.

“It shifts the financing model,” Magavi said. “It means that the utility can do what a utility is for, which is large, upfront investment and long-term payback for deliveries of a necessary human good.”

In recent years, the state has seen a handful of networked geothermal pilot programs announced. In 2020, the state’s Department of Public Utilities approved Eversource’s first-of-its-kind networked geothermal pilot program in Framingham, serving 36 buildings and about 140 residential and commercial customers.

In early 2024, National Grid announced a pilot program of its own at Dorchester’s Franklin Field public housing development, in partnership with the Boston Housing Authority. That project, planned to replace an aging boiler, will serve 129 of the development’s 450 units. National Grid didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Rate systems to pay for networked geothermal have yet to be set in stone. Needham said that it will have to happen before it can really take hold. But Eversource is currently exploring one approach.

Residential customers in its pilot pay $10 per month, plus their electricity bill which covers the energy to pump fluid through the system, while commercial customers pay $20 per month. Income-eligible residential customers receive a discount rate of $8 monthly.

From a utility perspective, use of geothermal, especially networked geothermal, “sort of aligns in a couple of different areas,” Needham said, pointing to the energy efficiency and decarbonization goals and the easy workforce transition.

It’s Framingham pilot kicked into gear late last year, Needham said, so it’s gone through a cold season. Now the utility is watching to see how it handles the summer. So far, he said, the system has operated as expected.

But networked geothermal isn’t a done deal. Another National Grid pilot program, slated to be built in Lowell, broke ground in 2023 but was cancelled in 2024, after the utility said it was no longer economically viable.

Utility-owned geothermal heating systems may offer other opportunities too. A pending energy package at the State House would give the state’s gas utilities the ability to construct big systems for individual customers.

Under a provision in Gov. Maura Healey’s Affordability, Independence, and Innovation Act, utilities would be able to work with a single large customer, like a college or hospital, to build a geothermal heating system.

Like networked systems, the brunt of the cost would be shouldered by the utility, letting the institution get the potentially cost-effective efficiency of geothermal heating and cooling without the high upfront cost, Lavinson said.

Utilities would handle the construction and operation, and the customer would pay back the cost through their utility bill over time. That solution might help convince bigger customers to take on these systems, Ryan said.

And, as clean energy efforts broadly are on the chopping block under the administration of President Donald Trump, geothermal may have escaped the worst of it.

While tax credits included under the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act around many renewables were largely axed in the administration’s so-called “Big Beautiful Bill,” sent to Trump’s desk July 3, commercial geothermal tax credits survived (residential ones were less fortunate).

“It’s actually one of the few topics that I like that still seems to be on the federal radar,” Ryan said. “They are interested in geothermal, where, at the same time, wind, solar, all those other ones are getting cut.”

Magavi, who has spoken with legislators about the technology, said she’s heard an appreciation from Republicans about the non-intermittent nature of geothermal — the earth isn’t cyclically going dark the way the sun does. And the technology has a legacy of research and production in the United States, she said, which might shift the politics around it.

“There is a kind of continuity of enthusiasm and support, even if there is a specific tax credit loss,” Magavi said.

A geothermal energy plant near the Salton Sea, California. Water pipes are shown in the foreground and steam exhaust in the background. PHOTO: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Geothermal for power generation

The less frequent application for geothermal — at least in the northeast — is to generate electricity. Unlike the heating and cooling systems, a longer pipe is used to get hot water from wells deep underground. As the hot water is pumped to the surface, it becomes steam, which is used to turn a turbine and generate electricity in much the same way that a coal power plant uses the burning of coal to create steam.

The system isn’t perfect — building it has some environmental impacts, and the water has to be replaced to avoid causing sinkholes — but it can offer cleaner, renewable energy.

Just not, for now, in New England.

That kind of technology currently requires specific underground deposits of hot water — or, per a developing technology, hot rock where water is pumped down into the rock to be heated into steam. Geologically speaking, this isn’t how this part of the country is constructed.

“The New England area does not have high-temperature anything underground,” Ryan said.

New innovations have moved the technology toward potentially being able to provide power generation in a wider array of locations, Magavi said.

Ryan said that there’s been research into an ambient temperature system to generate power, which would be less efficient, but could still be effective. For now, that technology simply isn’t ready, but Lavinson said that if it becomes available, it’s a solution the state would consider implementing to reach its decarbonization goals.

“If it turns out we do have the geology to do the deep geothermal that power generation requires, I think that, yeah, we’re going to seize that opportunity,” she said.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.